Chinese dialects in Singapore

In addition to Mandarin, various dialects are commonly spoken by Chinese Singaporeans. These are different from Mandarin, having developed in different regions in China.

The dialects of Singapore’s Chinese community are diverse and complex, with the five main dialects and their respective dialect groups (Hokkien, Teochew, Cantonese, Hakka, Hainan) being the most prominent, alongside other dialects such as Henghua (Henghwa, Hinghwa) and Shanghainese. In the early years, Chinese immigrants from southern China settled in groups based on their place of origin in China. This led to the formation of various local communities where different dialects were spoken. It has been pointed out that, “From the very beginning, the Chinese population was not a united one. It was divided into disparate groups distinguished not only by the dialects they spoke, but also by the locations where they congregated, worked and lived.”1

For example, the Hokkien people from the Minnan region typically use the Hokkien dialect; Teochew speakers, originating from the eastern part of Guangdong, use Teochew dialect; and Cantonese is spoken by the Cantonese people from the Pearl River Delta area. Sociologists have described this phenomenon as the Dialect Group Classification Rule.2

Colloquial expressions from Hokkien often find their way into everyday conversations in Singapore, making it a prominent dialect that transcends community boundaries.

The shift of Chinese dialects in Singapore

Using population census data gathered over several years, it is possible to trace the population proportions of various dialect groups (see Table 1). In the early days, despite sharing cultural traditions, Chinese people speaking different dialects often found it hard to communicate effectively with one another. They also observed different customs, which led to strong dialect group identities.

The start of the government’s Speak Mandarin Campaign in 1979, which had slogans such as “Speak more Mandarin and less dialects”, contributed to the decline of dialect usage in Singapore. After the campaign was initiated, the use of dialects in broadcasting was restricted. This, along with the country’s education bilingual policy, weakened the sense of identity within dialect groups. Dialects eventually became something used primarily by the older generation, as younger people lacked a conducive environment to learn them.

Population censuses conducted after 1980 continued to collect data on people’s dialect groups. This data does not necessarily indicate proficiency in a particular dialect.

Table 1: Proportion of Chinese dialect groups in the population from 1881 to 2020 (%)

| Dialect Groups | 1881 | 1931 | 1947 | 1957 | 1970 | 1980 | 2010 | 2020 |

| Hokkien | 28.8 | 43 | 39.6 | 40.6 | 42.2 | 43.1 | 40.0 | 39.3 |

| Teochew | 26.1 | 19.7 | 21.6 | 22.5 | 22.4 | 22.0 | 20.1 | 19.4 |

| Cantonese | 17.1 | 22.5 | 21.6 | 18.9 | 17 | 16.5 | 14.6 | 14.3 |

| Hainan | 9.6 | 4.7 | 7.1 | 7.2 | 7.3 | 7.1 | 6.4 | 6.1 |

| Hakka | 7.1 | 4.6 | 5.5 | 6.7 | 7.0 | 7.4 | 8.3 | 8.6 |

| Others | 11.3 | 5.5 | 4.6 | 4.1 | 4.1 | 3.9 | 10.5 | 12.3 |

| Total | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| Total Number of Chinese | 86, 000 | 418, 000 | 729, 000 | 1.09 million | 1.579 million | 1.856 million | 2.793 million | 3.006 million |

Source: Eddie Kuo and Luo Futeng, Diversity and Unity: Language and Society in Singapore, 6.

National and cultural identities

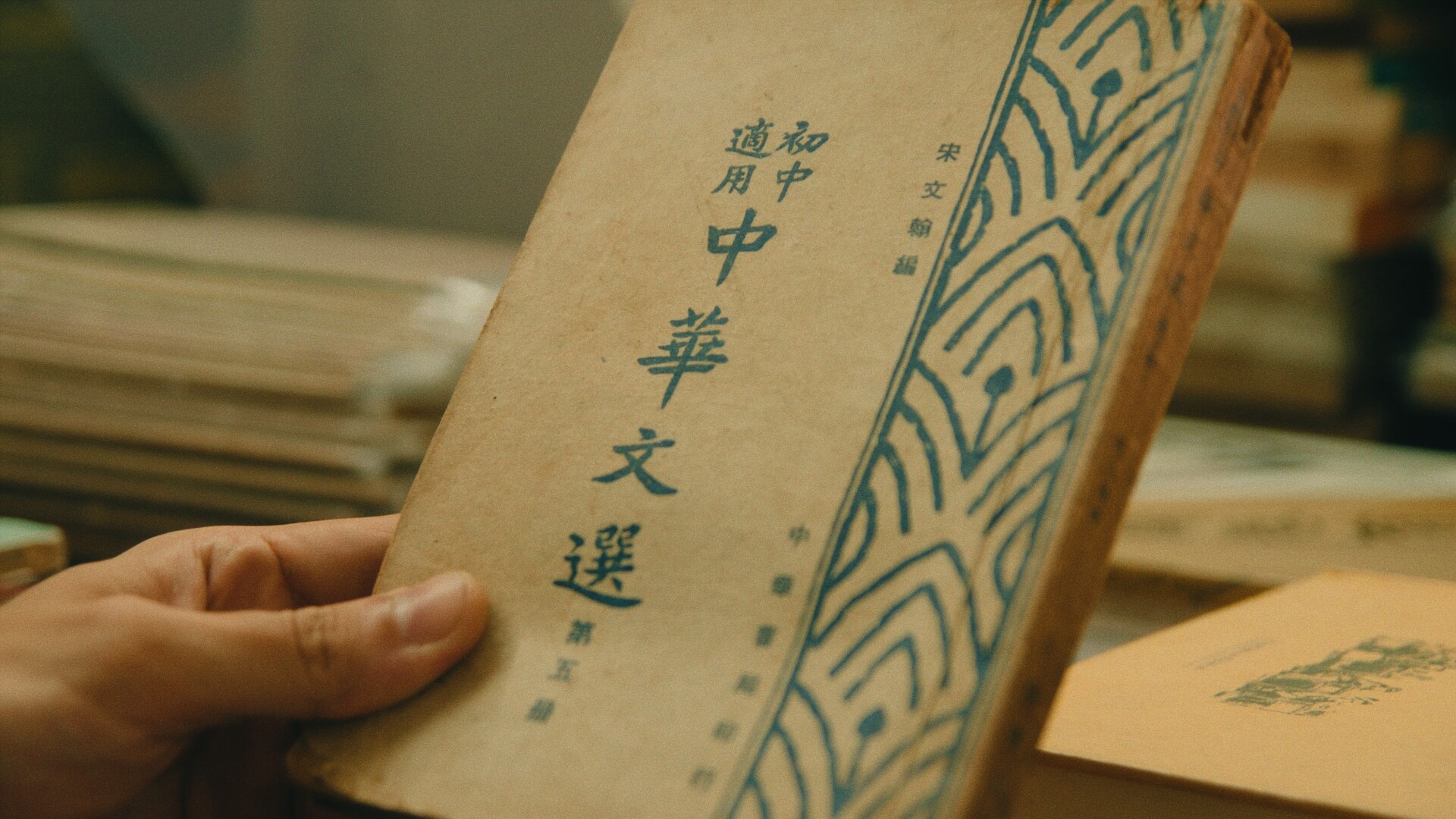

Dialects are not just tools for communication. They also serve as a bedrock for local Chinese culture and enable that culture to be transmitted. In traditional Chinese opera, folk songs, ditties, and theatrical performances make use of dialects — as do Hokkien gezai opera, Teochew opera, Hakka folk songs, and Cantonese opera.

As dialects decline in prominence, certain aspects of culture run the risk of fading away and being forgotten by younger generations. Members of the local community might have bemoaned the decline of dialects, but policymakers saw the presence of diverse Chinese dialects as an obstacle to forging a common identity among members of the young nation.

By the mid-20th century, as the number of Chinese immigrants swelled, the number of Chinese dialects spoken also increased to at least 12.3 Singapore’s founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (1923–2015) remarked, “Dialects were not only interfering with bilingual education, they were also dividing the Chinese community as those who spoke the same dialect tended to band together.”4

Today, Singapore’s bilingual education system encourages locals to learn a “mother tongue” — such as Mandarin, Malay, Tamil — in addition to mastering English. The government does not prohibit the learning and use of dialects.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡华族方言. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Leong Weng Kam, “The Evolution of the Chinese Language,” in 50 Years of the Chinese Community in Singapore, edited by Pang Cheng Lian (Singapore: World Scientific, 2016), 131–148. |

| 2 | Mak Lau-Fong, Fangyanqun rentong: zaoqi xingma huaren de fenlei faze [Dialect group identity: classification rules of early Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia] (Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, 1985). |

| 3 | Lee Kuan Yew, My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2011), 140. |

| 4 | Lee Kuan Yew, My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey (Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2011), 146. |

Chew, Cheng Hai. “Xinjiapo de yuyan jiaoyu yu yuyan guihua” [Language Education and Language Policy in Singapore]. Zhongguo yuwen [Studies of the Chinese Language], 1996(2), 125–130. | |

Hsu, Yun-Tsiao. Nanyang huayu lisu cidian [Dictionary of colloquial Nanyang Chinese], Book 3 of Nanyang pocket series. Singapore: World Book Company, 1961. | |

Hsu, Yun-Tsiao. Shiwu yin yanjiu [Study of 15 Tones], Book 5 of Nanyang pocket series. Singapore: World Book Company, 1961. | |

Lee, Kuan Yew. My Lifelong Challenge: Singapore’s Bilingual Journey. Singapore: Straits Times Press, 2011. | |

Mak, Lau-Fong. Fangyanqun rentong: zaoqi xingma huaren de fenlei faze [Dialect group identity: classification rules of early Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia]. Taipei: Institute of Ethnology, Academia Sinica, 1985. |