The Singapore Children’s Playhouse

The Singapore Children’s Playhouse (thereafter referred to as Children’s Playhouse) was an active children’s theatre group in the 1960s and 1970s. It had its roots in radio drama and later became a leader in stage performance, while also engaging in publishing activities to showcase the talents of its members.

Established on 12 June 1965, it was initially affiliated with the Chinese department of the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation. At the end of 1964, due to a shortage of Mandarin-speaking child actors, the radio station decided to conduct training classes. The radio director Fu Helin (1940–1990) was responsible for enrollment, while Thia Mong Teck (1936–2007), who was also a broadcaster and announcer, later took over as the mentor. 1Thia was one of the driving forces behind local radio dramas and youth theatre, and had a profound influence on Mandarin drama, stage performance, and other related fields.2

The original intention of the training classes was to cultivate radio drama actors, but Thia hoped the students could develop and learn in various areas. He thus set a goal for them to eventually perform on stage. The first training session commenced on the same day as the establishment of Children’s Playhouse.

The selection criteria for Children’s Playhouse were strict. Applicants had to have excellent academic performance as well as potential in singing and dancing. The first two training sessions attracted as many as 2,000 applicants, but only around 60 were ultimately selected. They were all students in primary and secondary school, and usually engaged in playhouse activities on weekends, including rehearsals, recordings, Mandarin voice training, and mime performances.

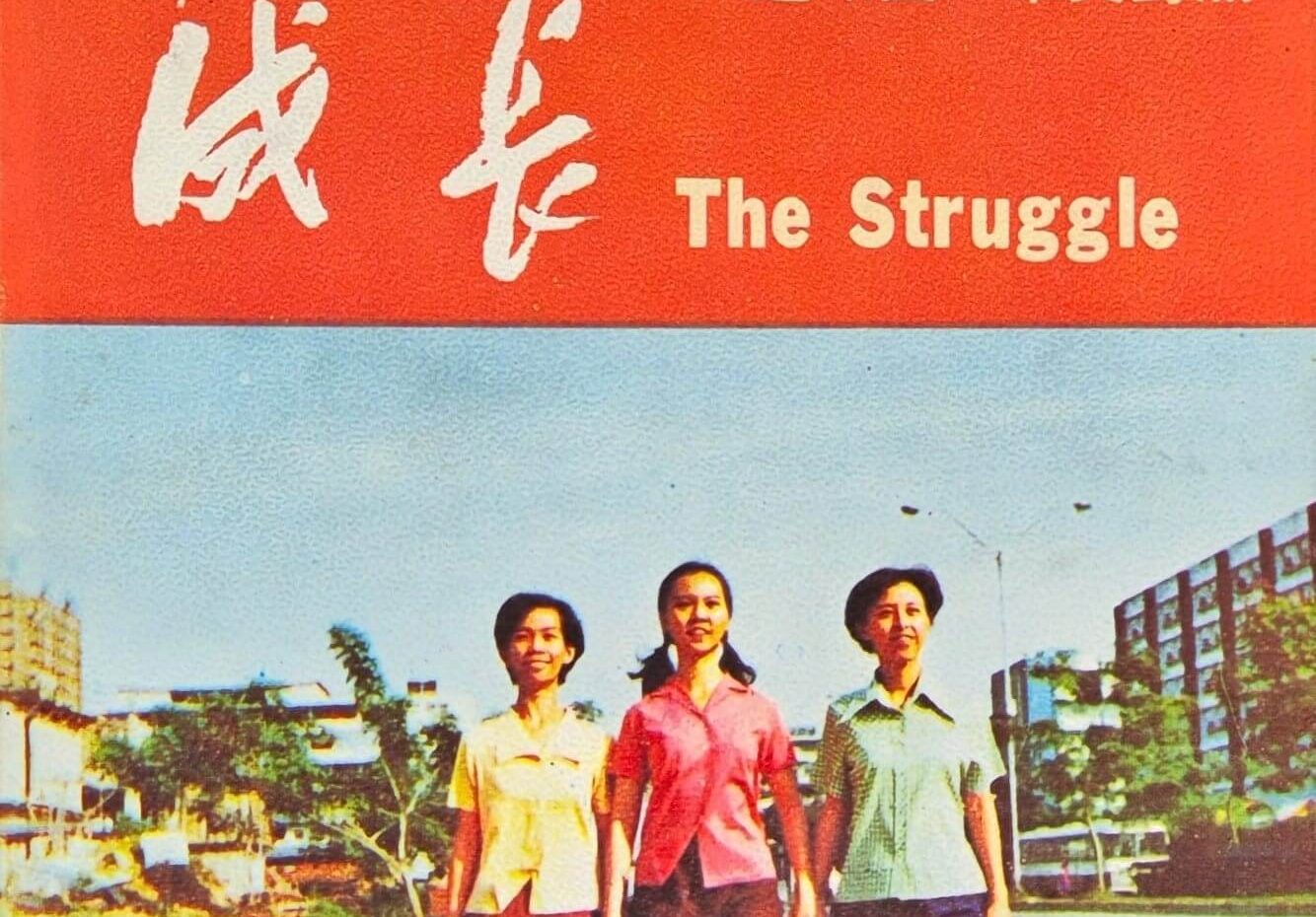

Growth and development

Thia adapted many world classics, fables, and folktales into radio dramas, which were performed by the playhouse’s students. Children’s Playhouse’s first radio drama, broadcast on 8 August 1965, was The Hunting Rifle Without Bullets, a piece of work from the former Soviet period. Besides children’s radio dramas, the playhouse also aired its first interview programme titled Yiyuan xinsheng (Art Garden New Voices) on 4 December of the same year, allowing listeners to get to know these young actors. Both weekly programmes gained popularity and gradually attracted a loyal audience for the playhouse, including listeners from across the strait in Malaysia. Around the same period, other arts groups targeting children were also established, including the Rediffusion’s Children’s Drama Group, which was established in 1966 and later renamed the Youth Children’s Drama Group.

A year and a half after its establishment, Children’s Playhouse made its stage debut in December 1966, staging Children’s Playhouse Night at the Victoria Theatre. Tickets for all five nights were sold out. Due to the enthusiastic response from the audience, the three one-act plays performed in the show, Borrowing an Umbrella, Dormitory Turmoil, and Before and After Children’s Day, were later recorded and broadcasted as television programmes, giving those who missed the live performances the opportunity to watch them.

The most iconic performance of the playhouse was the multi-act play The Watch, which was staged seven times at the Victoria Theatre in April 1968 and adapted into a television programme. Later, Children’s Playhouse collaborated with the television station to produce Deep Benevolence and two single-unit dramas, Lost Melody and Rail.

From 1968 to 1969, the playhouse established multiple interest groups, including literary arts; fine arts; men’s, women’s, and children’s choruses; dance, piano, accordion, harmonica, and photography groups. As the playhouse developed and matured, they also established brass bands and traditional Chinese orchestras.3

Children’s Playhouse ventured into publishing as well, releasing the first issue of Camel Art Literary Weekly in January 1969. The name Camel came from a supplement page created by Min Bao in 1968, when Thia was invited to serve as its editor-in-chief. Later, The Camel Art Publishing House was formally established in March 1970, publishing magazines such as Xiju tiandi (Theatre World) and Nianqing ren (Young People). At its peak, it had nearly 40 full-time members. However, it dissolved in February 1976 after only a few years of operation.

In 1970, the radio station ceased broadcasting children’s radio dramas and Yiyuan xinsheng. Thia resigned from the radio station, and almost all the members of the playhouse left with him. Following their departure, Children’s Playhouse became an independent organisation and began to professionalise. The playhouse relocated several times in search of a suitable headquarters for its activities, eventually settling in Thia’s father-in-law’s row of old bungalows on Arthur Road in Katong. As its members grew older, The Youth Playhouse was officially established on 3 March 1971.

At its peak, The Singapore Children’s Playhouse and The Youth Playhouse had 500 members. Their performances were often sold out, with a record of up to 31 shows per run. The highest number of audience members they ever witnessed exceeded 30,000. During its 15-year existence, Children’s Playhouse produced a total of 13 stage performances and nurtured a generation of excellent Chinese-speaking performers.

Eventual closure

Thia announced the suspension of the playhouse’s activities in 1976, despite it being at the peak of its popularity. That year, many drama workers were arrested due to their involvement in political activities. In a 2005 interview, Thia openly admitted that in light of the social situation at the time, he did not want to see the playhouse’s activities spiral out of control and lead to similar incidents. Therefore, he believed it was necessary for the playhouse to suspend its activities and reconsider its future direction.4

The final performance by Children’s Playhouse was held at the Little World Children’s Arts Evening in 1980. After that, Children’s Playhouse officially became history. However, its influence had deeply penetrated the local Chinese cultural and education community. Even today, many former members still uphold the spirit of the playhouse and actively nurture future generations of successors in the theatrical arts. For example, the Hokkien Huay Kuan Arts and Cultural Troupe, which started its children’s performing arts training classes in 1987, was co-founded by former members of Children’s Playhouse, including Perng Peck Seng, Huang Shuping, Ng Siew Ling, and Shi Manhua. Another former member Chua Soo Pong established the Chinese Opera Institute in 1995.

In the early years of Singapore’s nation-building, while various industries were still emerging, cultural development had yet to be fully realised. It was during this time that Children’s Playhouse emerged, nurturing hundreds of cultural talents. Figures such as Wah Liang (1953–1995), Wu Xueni, Chua Soo Pong, Lim Sau Hoong, Perng Peck Seng, Wong Lin Tam, Woo Wei Quee, Ho Seo Teck, Chak Chee Yoke, Ng Siew Leng, Lim Jen Erh, Yang Fan, Tan Tiaw Gem, and others who were cultivated by the playhouse later became active members in theatre, broadcasting, television, culture, and the education sectors. Organisations like Children’s Playhouse and Rediffusion Children’s Drama Group played a crucial role in laying the foundation and sowing the seeds for the inheritance of Chinese culture.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡儿童剧社. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Chia Yen Yen, “Tuanti yi jiesan haiban 50 zhounianqing, xiri sheyuan qingqian ertong jushe 35 zai” [Group dissolved yet held 50th anniversary celebration, former members emotionally connected to Children’s Playhouse for 35 years], Lianhe Zaobao, 15 June 2015. |

| 2 | Chew Boon Leong and Lim Meow Nar, “Huayu xiju jie qianbei Cheng Maode gan ai shishi” [Veteran figure in Chinese drama Thia Mong Teck passes away from liver cancer], Lianhe Zaobao, 1 February 2007. |

| 3 | Liu Li, “Yige wenhua tuanti yishi qing, ting Cheng Maode laoshi shuoshu” [A lifetime of dedication to a cultural organisation: 55th anniversary of The Singapore Children’s Playhouse], Lianhe Zaobao, 9 July 2020. |

| 4 | Wong Jia Kit, “Ertong jushe cong guangbo zoushang wutai, ting Cheng Maode laoshi shuoshu” [From radio to stage — Children’s Playhouse: Listening to Thia Mong Teck’s stories], Yuan Magazine, May 2005, 25. |

The Singapore Children’s Playhouse 50th Anniversary Celebration Preparatory Committee. Mangguo shu xia: Ertongju she chengli 50 zhounian jinian teji [Under the mango tree: The Singapore Children’s Playhouse 50th Anniversary special commemorative edition]. Singapore: The Singapore Children’s Playhouse 50th Anniversary Celebration Preparatory Committee, 2015. | |

Quah, Sy Ren. Xiju bainian: Xinjiapo huawen xiju 1913–2013 [Scenes: a hundred years of Singapore Chinese language theatre 1913–2013]. Singapore: Drama Box, National Museum of Singapore, 2013. |