Chinese culture and music education in Singapore

It is challenging to define Chinese music in an immigrant indigenised society like Singapore. For the last seven centuries,1Chinese immigrants held on to close filial and familial ties with China, while their English-speaking counterparts gravitated towards Western influences, especially since Singapore was governed by the British East India Company from 1819. Understanding Singapore’s approach to music education is complex, largely in the way it is defined in educational policies regarding both curricular and extracurricular settings, as well as in policies and practices regarding arts and culture.

Documents detailing the large-scale migration of southern Chinese from mainland China in the 19th century to Singapore point to the emergence of local traditions and practices (including the arts) among the community, who continued to maintain ties with mainland China.2Singapore’s political landscape underwent numerous shifts — from British rule, to the Japanese occupation (1942–1945), back to British colonial status again, before attaining self-governance in 1959 and eventually political independence in 1965. These transitions complicated identity formation and led to the emergence of two distinct Chinese communities: localised Chinese communities who kept in touch with their Chinese roots, and English-speaking communities who were influenced by non-mainland Chinese traditions and practices. The former community mainly attended Chinese-medium schools in Singapore, whose textbooks and curriculum included folk songs/folk music. They were largely supported by government aid, as well as donations and resources from clan associations and philanthropists.3

After the Japanese Occupation, the China Song, Dance and Drama Company participated in a large-scale event (loosely translated as the “Thousand People Picnic”) in 1947, organised by the students of Chinese High School and Chung Cheng High School. They performed songs such as “Yellow River”, “Ode to Nanda (Nanyang University)”, “Rubber Plantation, Our Mother”, and “My Homeland is a Mountain of a Thousand Treasures”, which continued to resonate with listeners until the early 1960s.4 From the 1950s, the proliferation of these folk tunes led to the formation of a new type of Chinese orchestra in post-World War II Singapore.

Local Chinese orchestras

Chinese orchestras in Singapore began to incorporate local elements into their performances as early as the 1960s. For instance, in 1968, the People’s Association Cultural Troupe presented a fusion of Chinese and Western instruments alongside performances by arts and culture groups from diverse local communities.5

Many students began to learn and perform this form of new Chinese orchestral music despite a lack of instruments, formal structure, family background, musicians, and resources. Chinese orchestral music was also broadcasted alongside popular music on Rediffusion Singapore,6 the country’s first cable-transmitted, commercial radio station, to reach a larger audience within the local Chinese community. Getai troupes like Man Jiang Hong, Shangri-La, New Nightclub, Feng Feng Song and Dance Troupe, Broadway, and the famous Zhang Lai Lai Song and Dance Troupe were all well-received by audiences at the New World Amusement Park.7

The trio of amusement parks — New World, Great World, and Gay World (formerly Happy World) — were key venues in Singapore’s thriving nightlife scene in the 1950s. They hosted contemporary popular dance crazes such as cha-cha, rumba, tango, and more, which were accompanied by live band performances. These became the hallmark of local entertainment for the Chinese community in Singapore. At that time, popular singers, the “stars of those days”, such as Huang Qing Yuan and Chin Whai were known in the 1950s and 1960s for their rendition of ballads. Rita Chao was known for her Agogo style singing while Sakura Ting was well known for yodelling in some of her ‘country’ style, western songs, apart from her already large on-screen reputation. Sakura Ting had an international appeal in Hong Kong and Indonesia. Poon Sow Keng yodelled as well while Zhang Xiao Ying’s focus was more ballads and other slower tempo songs which made her more popular in the late 70s and early 80s.

Alongside Chinese orchestral traditions and popular music, two uniquely Singaporean expressions of folk music genres emerged. The first was shiyue,8 which was similar to the art song in Euro-American traditions. Pan Cheng Lui and Zhang Fan were the two most well-known figures in the scene while they were still studying at Nanyang University’s (which was located at the present site of Nanyang Technological University) Faculty of Arts and Humanities. As members of the Chinese Poetry Club, they translated their poems into songs accompanied by the guitar. Over time, the demands of work and other commitments, as well as the intensity of their creative endeavours, caused shiyue practitioners to gradually fade from the spotlight.

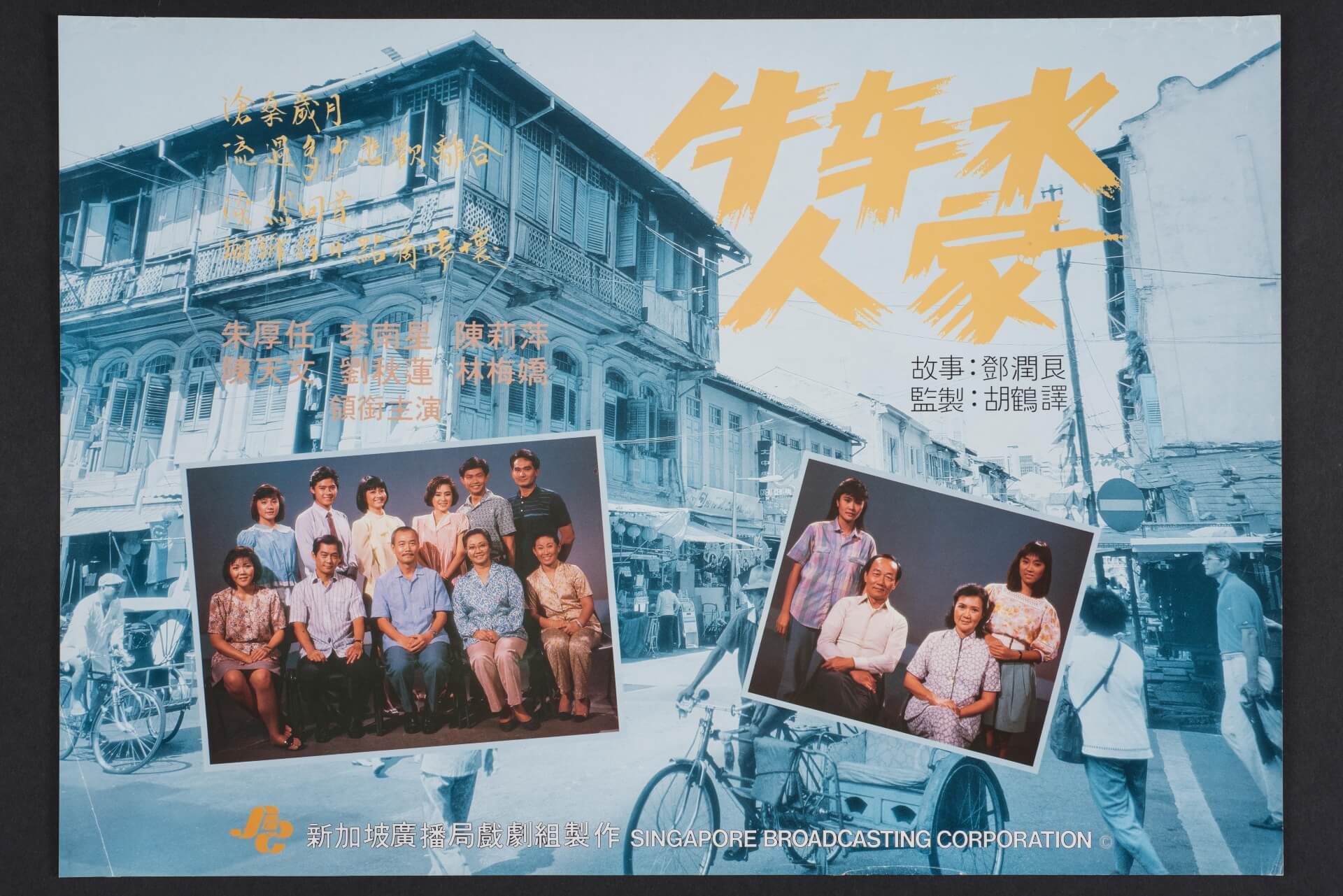

Xinyao, the second genre, emerged with shiyue and gained prominence as not just a unique expression of Singapore Chinese identity, but also a product of creativity from local youth for whom Mandarin was their first language.9This coincided with a seismic shift towards a concerted and larger-scale production of local drama series in Mandarin based on Singaporean experiences, such as National Service (The Army Series, 1983), the Japanese Occupation (The Awakening, 1984), and the quintessential local coffee shop (Kopi-O/The Coffeeshop, 1985).

While xinyao’s prominence may have been influenced by the growing use of Mandarin as a unifying language within the local Chinese community, it also undeniably consolidated the place of local Chinese music in Singapore’s new wave of television drama series. During the 1980s, brothers Lee Wei Song and Lee Si Song, despite their tangential connections with xinyao, wrote several theme songs for a fledgling local Mandarin drama series supported by the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (now known as Mediacorp). That era marked xinyao’s heyday, characterised by numerous album releases and a strong presence in public spaces like community clubs. One of xinyao’s most prolific pioneers, Liang Wern Fook, was awarded the Cultural Medallion in 2010, Singapore’s highest artistic accolade.

Efforts to develop Chinese music education

From 1959, Singapore’s Ministry of Education initially positioned music as a peripheral subject outside of the core curriculum, as alternative to art and handwork on Saturday mornings or outside school hours. Its stance later evolved, and music was promoted as an avenue for community bonding and engagement. Efforts both within and outside the core curriculum, on top of initiatives by the Ministry of Culture, sought to strengthen inclusivity across communities in Singapore, despite challenges like a shortage of teachers or educational resources. When the bilingual policy was introduced in 1966, second-language teachers (now known as Mother Tongue teachers) were encouraged to also teach music and familiarise themselves with musical repertoire and resources, with the intention of fostering greater inclusivity in the classroom settings.10

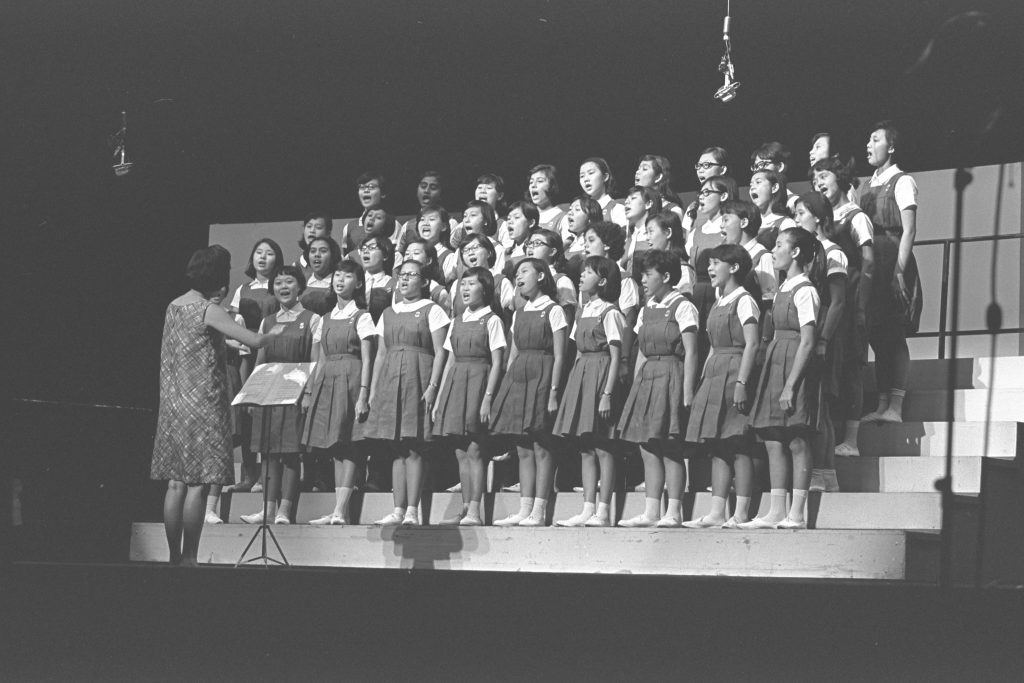

The Ministry of Education organised its first Singapore Youth Festival on 18 July 1967, with the aim of providing opportunities for children from different communities to sing and dance together. Separately, the newly established National Theatre Choir held its inaugural concert in 1968. A recording of its performance later sold out in record time, attesting to the quality and appeal of performing Chinese songs. A singing competition organised in the same year by Radio Television Singapura lasted for almost six months, establishing a close network of Chinese choir leaders and singers. Even after the competition was discontinued, singers from these Chinese choirs continued to collaborate on joint concerts to sustain interest in Chinese songs.

Another significant initiative to promote Chinese music was the Chinese Music Festival organised by the Ministry of Culture, which played a crucial role in fostering a shared sense of identity among Chinese musicians in Singapore and promoting artistic excellence. The festival featured a variety of musical styles and traditions, including Chinese classical and folk music. Consequently, musicians who performed there were often invited to set up school Chinese orchestras, which then went on to participate in the annual Singapore Youth Festival starting in the 1980s. The growth and development of Chinese music among students, musicians, and audiences eventually laid the foundation for the establishment of the Singapore Chinese Orchestra in 1997.

Today, music education in public schools in Singapore promotes music, albeit peripherally, as a crucial social anchor for students with exposure to the diverse musical traditions in multicultural Singapore. Chinese music of all forms and genre — from Chinese instrumental ensembles, to Chinese orchestras, to Chinese popular music (most notably xinyao) — has become an integral part of Chinese music education in Singapore schools. Songs such as “The More We Get Together” (sung in Chinese), “Zao Qi Shang Xue Xiao” (Going to School), “Xiang Xin Wo Ba Xin Jia Po” (Believe in Me, Singapore), “Xi Shui Chang Liu” (Friendship Forever), “Xiao Ren Wu De Xin Sheng” (Voices from the Heart), and “Dui Shou” (Competitor) have gained recognition as national and community songs. Moreover, the 2023 General Music Programme syllabus forges direct connections between classroom music learning and key cultural institutions like the Esplanade, Singapore Chinese Orchestra, and Singapore Symphony Orchestra, with support from the National Arts Council – known as Performing-Arts Based Learning. In doing so, xinyao has regained prominence under the Teaching Living Legends programme at the Singapore Teachers Academy of the Arts, which aims to enhance the professional curriculum for music teachers in Singapore schools.

Any discussion of Singapore Chinese culture in the context of music education cannot ignore multiple interconnected themes, from music in Chinese street and staged opera accompanied by musical ensembles, to Chinese orchestral traditions, to the prevalence of Chinese popular music among the Chinese community, to the enduring significance of xinyao. Ultimately, understanding these different facets is an ongoing process of meaning-making.

| 1 | Refer to Kwa Chong Guan, Derek Heng, Peter Borschberg, Tan Tai Yong, eds., Seven Hundred Years: A History of Singapore (Singapore: Marshall Cavendish, 2019). |

| 2 | Lena Heng, “‘Singaporean performance’ in Singapore’s Chinese orchestral practice: What is it? Where is it?”, in Is there such a thing as Singaporean performance, edited by Lena Heng and Sarah Weiss (Graz, Austria: Shaker Verlag, 2023), 309–334, 313. |

| 3 | S. Gopinathan, “Modernising madrasah education: The Singapore ‘national’ and the global”, in Rethinking Madrasah Education in a Globalised World, edited by Mukhlis Abu Bakar (London: Routledge, 2017), 65–75. |

| 4 | Chua Soo Pong, “Chinese Performing Arts”, in A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, edited by Kwa Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim (Singapore: Word Scientific Publishing, 2019), 573–614. |

| 5 | Heng, “Singaporean performance”, 309–334, 319. |

| 6 | Heng, “Singaporean performance”, 309–334, 319. |

| 7 | Eugene Dairianathan and Phan Ming Yen, A narrative history of music in Singapore 1819 to the present (Singapore: National Institute of Education, 2015), 422–423. |

| 8 | Dairianathan and Phan, A narrative history of music in Singapore, 195–197. |

| 9 | Dairianathan and Phan, A narrative history of music in Singapore, 431–449. |

| 10 | Eugene Dairianathan, “Paths to a Whole: Placing Music Education in Singapore”, in Education in Singapore: People-Making and Nation-Building, edited by Lee Yew-Jin (Singapore: Springer, 2022), 319–342. |

Dairianathan, Eugene. “Arts Policy, Practice and Education: Questions of Use/r values”. In Artistic Thinking in the Schools: Towards Innovative Arts in Education Research for Future Ready Learners, edited by Pamela Costes-Onishi, 19–37. Singapore: Springer, 2019. | |

Dairianathan, Eugene. “Paths to a Whole: Placing Music Education in Singapore”. In Education in Singapore: People-Making and Nation-Building, edited by Lee Yew-Jin, 319–342. Singapore: Springer, 2022. |