Tua Pek Kong worship among the Chinese in Singapore

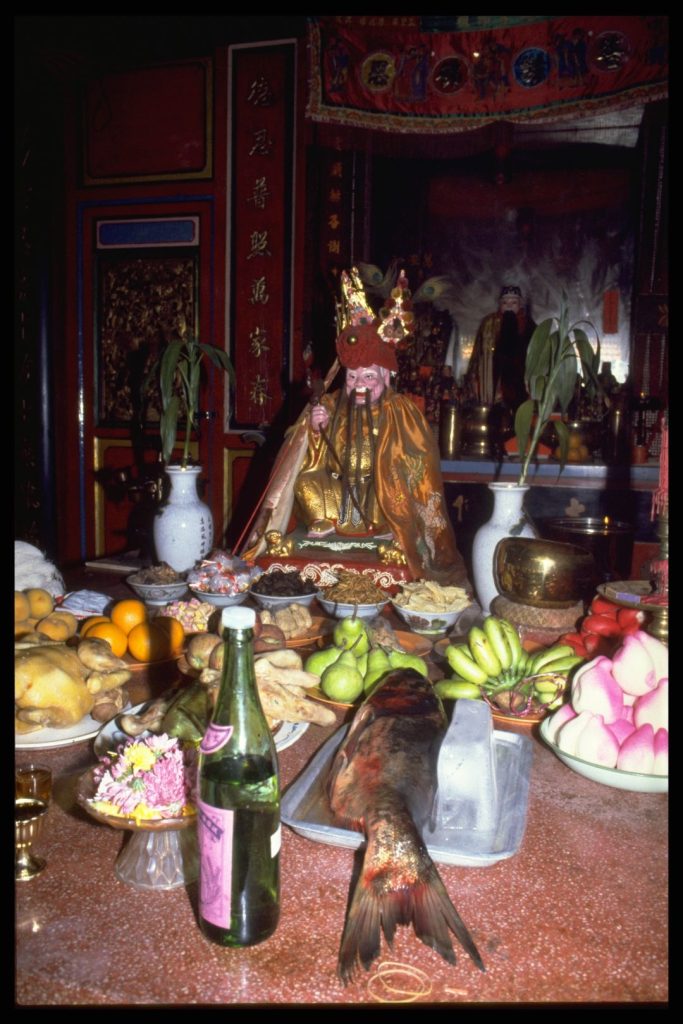

Tua Pek Kong, also known as the God of Prosperity and Virtue, has been widely venerated in Singapore, especially by early Chinese settlers. The worship of Tua Pek Kong dates back to the 19th century, when temples served religious and social functions for migrant communities. Beyond traditional temples, shrines dedicated to the deity are common in public spaces, reflecting his role as a local protector. Tua Pek Kong worship often overlaps with other religious traditions, highlighting Singapore’s multicultural and syncretic religious landscape.

A general history

Several of the oldest temples in Singapore, mostly located within the city area, are associated with the worship of Tua Pek Kong, reflecting the deity’s close association with the earliest Chinese settlers in the region. The most notable is Fuk Tak Chi Temple (founded in 1824), one of the oldest mutual aid organisations among the Hakka and Cantonese migrants in Singapore. Along with the adjoining Ying Fo Fui Kun, it provided vital connections and support for these communities.1

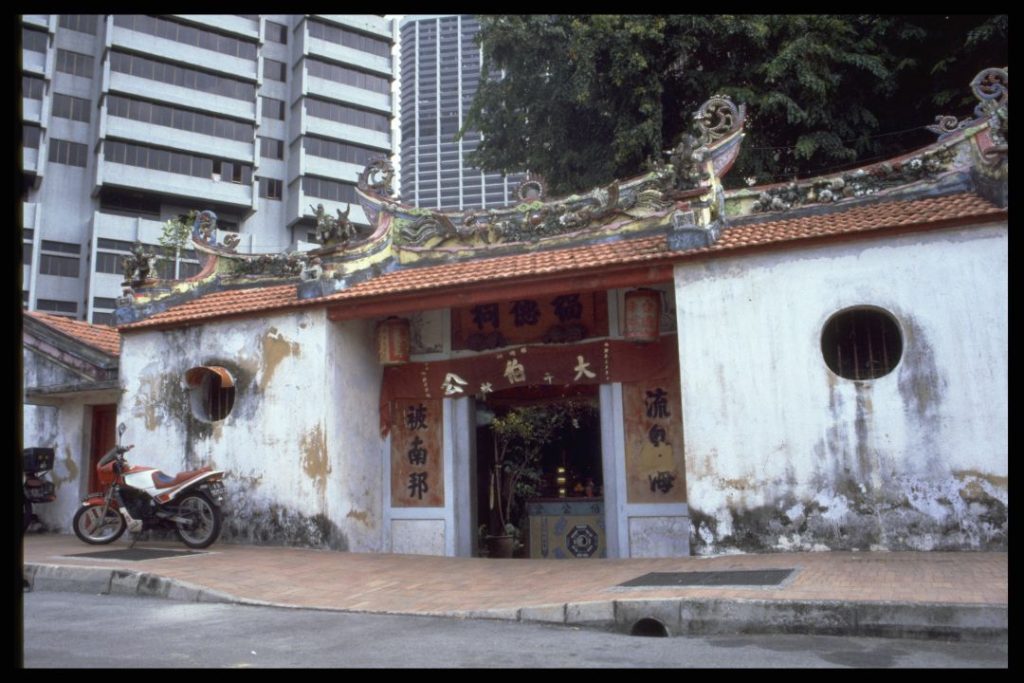

Another significant temple is the Hock Teck See temple (also known as Fook Tet Soo Khek temple, founded in 1844), which was frequented by the Hakka and Cantonese communities. The temple, located near Palmer Road next to the Keramat Habib Noh (1788–1866), originally stood by the coast before land reclamation projects altered the landscape. It is said that Hadhrami Arab saint Habib Noh enjoyed the operas performed at the temple when he was alive.2Even today, it is common for Chinese devotees of Tua Pek Kong to visit the keramat and make donations, underscoring the multi-ethnic and multi-religious encounters that define Singapore, a city positioned at the crossroads of South and East Asia’s trade, migration, and travel routes.

Not all prominent Tua Pek Kong temples were located in the city area. One example is Soon Thian Keing Temple (established c. 1820–1821), which was originally situated along Malabar Street, later moving to Albert Street, and eventually settling permanently in Geylang. This temple’s stelae mark it as one of the oldest Chinese religious institutions in Singapore.3 Another important temple is the Fu Shan Gong on Kusu Island, whose significance as a pilgrimage site has been noted since the mid-19th century (c. 1845).4Every year, during the ninth lunar month, boatloads of devotees travel to the temple during the Kusu pilgrimage season. Before land reclamation in the 1970s connected the two surrounding islands that now make up Kusu Island, people would take small boats between the islands of the Keramat Dato Syed Abdul Rahman (birth and death years unknown) and the Tua Pek Kong temple, especially when high tides separated them.5

The veneration of Tua Pek Kong in Singapore transcends the boundaries of dialects, occupations, and places of origin. The Mun San Fook Tuck Chee near Kallang River, for example, was founded by immigrants from Guangdong in the 1860s, who naturally made up a significant number of its devotees. Most of them were involved in the brickmaking industry. The temple served as a community centre for the area’s workers and hosted various community activities for schools and martial arts associations. A fire lookout tower was also built in front of the temple.6Another example is Goh Chor Tua Pek Kong, which was established in 1847 and maintained by Fujianese coolies who worked on the sugarcane plantation of Joseph Balestier (1788–1858), the first American consul in Singapore. Today, Goh Chor Tua Pek Kong is one of the few temples under the management of Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan.7

Tua Pek Kong shrines, altars, and temples

Although Tua Pek Kong is widely venerated in Singapore, the relationships that individuals have with the deity are often difficult to characterise. In his seminal paper “Who is Tua Pek Kong?”, historian Jack Chia observed that the deity has multiple identities among the overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia. He suggested that devotees in the region typically share a personal relationship with him, viewing him as a local protector.8 This perception persists today, as shown in a recent study on shrines, which found that small communities often pool resources to fund altars dedicated to Tua Pek Kong. These altars can be found in bus interchanges, food centres, and street shrines, providing spaces for communal worship.9 Like most Chinese shrines, these altars often feature a censer, usually accompanied by an image of the deity it is dedicated to.

In some places, Tua Pek Gong is regarded as a local guardian of the area’s wandering spirits, leading to his veneration during the seventh lunar month. He is typically represented by an image or emblazoned characters bearing his name. In addition, given the overlapping cosmological and theological systems of Chinese religions in Singapore, it is common to find altars dedicated to both Tua Pek Kong and a local earth deity (like Tudigong or Tangfan Dizhu Shen) in shrines and temples, with worship rituals conducted consecutively.

The way Tua Pek Kong is conceived can vary based on one’s place of origin. Devotees of Chaoshanese origin often associate Tua Pek Kong with the deity known as Gan Tian Da Di. Unlike the conventional depiction of the deity as a smiling elderly man in gentry attire, the Chaoshanese Tua Pek Kong appears as an armoured warrior wielding a sword and seated on a throne with his legs resting on a tiger.10This particular representation of Tua Pek Kong can be found in the Tong Xing Gang Shen Hui Da Bo Gong shrine, which was established since at least 1870 (based on an incense censer in the temple) and is now located in the United Five Temples of Toa Payoh, as well as the Kampong Tengah Thian Hou Keng, now part of the Sengkang Combined Temple (established c. 1930).

Amalgamation of cultures

The close relationship between Tua Pek Kong worship and its respective local communities of devotion have presented multiple opportunities for inter-ethnic interaction. As mentioned, worship at keramat shrines and Datuk Gong worship have often overlapped with the worship of Tua Pek Kong. However, what is often overlooked is the extent to which Hindu temples — particularly those dedicated to Ganesha and Muneeswaran — have shared religious spaces with Tua Pek Kong worship.11

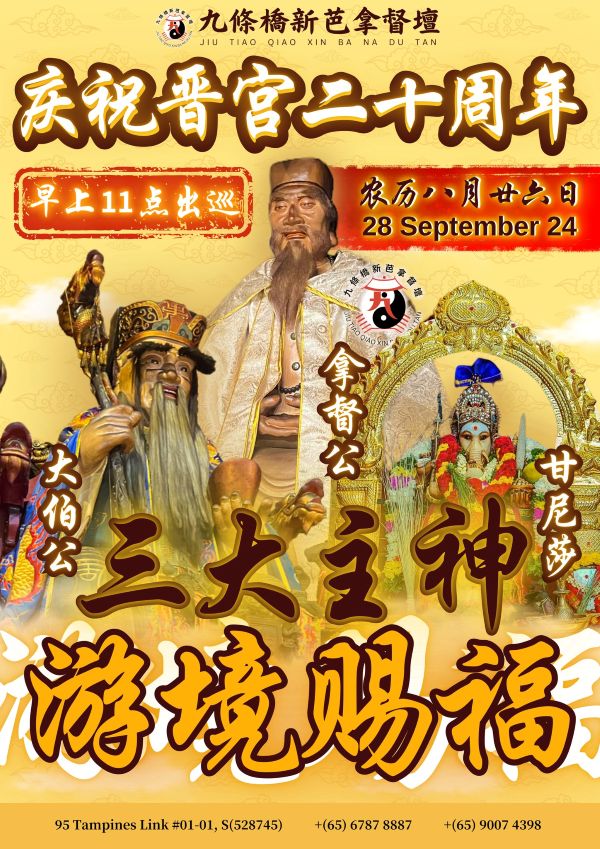

For instance, Hock Huat Keng in Yishun is housed under the same roof as the Sri Veeramuthu Muneeswarar Temple, which has a Hindu shrine dedicated to the deity Muneeswaran. Similarly, at the Jiutiaoqiao Xinba Nadutan, which recently celebrated its 20th anniversary, Tua Pek Kong is the primary deity that is worshipped, though his altar is flanked by one dedicated to Ganesha. Additionally, a separate backroom is dedicated to the worship of Datuk Gong, complete with a miniature water fountain and turtles. Ganesha is also venerated as one of the secondary deities on a shared altar.

At the Loyang Tua Pek Kong, Ganesha has his own dedicated altar in a separate section of the temple complex, along with other sections for other Hindu deities and a Datuk.12 The Sze Cheng Keng Temple and Sri Muneswarar Peetam also share the same premises, further exemplifying the religious exchange and amalgamation of cultures in these places of worship.13

| 1 | Zeng Ling, “Shetuan zhangben yu er zhan qian Xinjiapo huaren shetuan jingji yanjiu: Yi Jiaying wushu shequn zong jigou Yinghe Huiguan wei ge’an” [Society Account Books and the Economic Study of Chinese Societies in Pre-WWII Singapore: A Case Study of the Jiaying Wushu Clan’s Central Organisation, Yinghe Huiguan], Zhongguo shehui jingji shi yanjiu [Research in Chinese Social and Economic History] 4 (2016): 65–77. |

| 2 | Teren Sevea, “Writing a History of a Saint, Writing an Islamic History of a Port City,” Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Working Paper 27 (2018): 11–12. |

| 3 | Kenneth Dean and Hue Guan Thye have compiled sources regarding the date of the temple’s establishment in Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore, 1819–1911 (Singapore & Guangxi: National University of Singapore Press and Guangxi Normal University Press, 2017), vol. 2, 1165–1166. |

| 4 | “Cheang Hong Lim,” The Straits Times, 14 August 1875, 2. |

| 5 | Jack Meng-Tat Chia, “Managing the Tortoise Island: Tua Pek Kong Temple, Pilgrimage and Social Change in Pulau Kusu, 1965–2007,” New Zealand Journal of Asian Studies 11, no. 2 (2009): 72–95. |

| 6 | Chin Fook Siang, oral history interview by Kiang-Koh Lai Lin, Economic Development of Singapore, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 004298), reel 2 of 6. See also Loo Say Chong and Ang Yik Han, Toutao zhibao, Wanshangang Fudeci lishi suyuan [A Boon Returned: The History of Mun San Fook Tuck Chee] (Singapore: Selat Society, 2008); Ang Yik Han, Xiang qing ci yun: Shagang cun he wanshan fudeci de liubian yu chuancheng [A Kampong and Its Temple: Change and Tradition in Kampong Sar Kong and the Mun San Fook Tuck Chee] (Singapore: Wan Shan Fu De Ci, 2016). |

| 7 | Zhang Jiaying, “Wucao dabogong miao jiang jiao fujian huiguan dali, Huiguan chengnuo wanzheng baoliu miaoyu” [The Wu Cao Tua Pek Kong Temple to Be Managed by the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, with a Commitment to Preserve the Temple in Its Entirety], Lianhe Zaobao, 22 March 2024. |

| 8 | Jack Meng-Tat Chia, “Who is Tua Pek Kong? The Cult of Grand Uncle in Malaysia and Singapore,” Archiv Orientální 85, no. 3 (2017): 439–460. |

| 9 | Lim Khek Gee Francis, Kuah Kuhn Eng and Lin Chia Tsun, Chinese Vernacular Shrines in Singapore (Singapore: Pagesetters Services, 2023). |

| 10 | See Kenneth Dean and Hue Guan Thye, Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore: 1819–1911 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2017), xxxvi, for one interpretation of the deity’s identity. |

| 11 | Vineeta Sinha, A New God in the Diaspora? Muneeswaran Worship in Contemporary Singapore (Singapore: Singapore University Press; Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2005), 116, 230–234. |

| 12 | Yuan Zhong, “Nanyang kongjian de shanbian: Xinjiapo huaren miaoyu de duoyuan zayi xing” [The Evolution of Nanyang Space: The Plural and Diverse Nature of Chinese Temples in Singapore], Huanan Ligong Daxue Xuebao (Shehui Kexue Ban) [Journal of South China University of Technology (Social Science Edition)] 19, no. 6 (2017): 79. |

| 13 | “Two Gods, One Temple | Sze Cheng Keng Taoist Temple & Sri Muneswarar Peetam Hindu Temple,” Our Grandfather Story, 16 May 2019. |

Dell’Orto, Alessandro. Place and Spirit in Taiwan: Tudi Gong in the Stories, Strategies and Memories of Everyday Life. London: Routledge, 2003. | |

Ho, Phang Phow and Chen, Poh Seng, eds. Bainian gongde bei nan bang: Wanghai dabogong miao jishi [The Living Heritage: Stories of Hock Teck See temple]. Singapore: Singapore Char Yong (Dabu) Association Hakka Culture Research Office and Hock Teck See temple, 2006. | |

Hsu, Yun Tsiao. “Dabogong erbogong yu bentougong” [Tua Pek Kong, Second Uncle Gong, and Bentou Gong]. Journal of the South Seas Society 7, no. 2 (1951): 6–10. | |

Xu, Yucun, ed. Zuqun qianyi yu zongjiao zhuanhua: Fude zhengshen yu dabogong de kuaguo yanjiu [Ethnic Migration and Religious Change: Transnational Research on the God of Prosperity, Virtue, and Morality and Tua Pek Kong]. Hsinchu: National Tsing Hua University College of Humanities and Social Sciences, 2012. | |

Yang, Baoquan, ed. Fude zhengshen: Xinjiapo lu banrang shun tiangong erbai zhounian jinian tekan [The God of Prosperity: Bicentennial Commemorative Publication of Lu Banrang Shun Tian Gong, Singapore]. Singapore: Soon Thian Keing, 2012. |