Traditional trades of the Hakka community in Singapore

In the 1950s, the Hakkas made up only about 7% of Singapore’s Chinese population.1 The larger dialect groups, such as the Hokkiens, were more influential in the business sector and controlled some of the emerging economic industries such as banking, insurance, rubber processing, and manufacturing.2 While their counterparts in Malaysia and Indonesia found work in the developing mining industry in those countries, the Hakkas in Singapore did not have the same opportunities. They had to work hard to carve out an economic space for themselves.

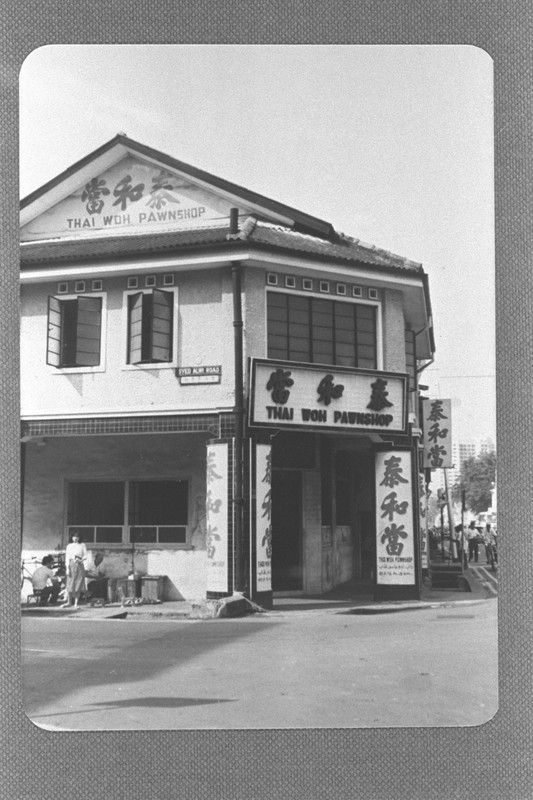

Leaders of the pawnbroking industry

The Hakkas’ early occupations were primarily in trades such as the production of leather goods and rattan furniture, and construction — jobs of the working class.

However, there is one industry they have dominated since they first ventured into it: pawnbroking. According to historical records and He Qianxun’s 2005 book Xinjiapo diandang ye zongheng tan (Pawnbroking in Singapore), the first pawnshop in Singapore was Sheng He Dang, which was opened in 1872 by Dapu native Lam Chiew San (1843–1930). According to He, the number of pawnshops in Singapore increased from 32 in 1958 to 92 in 2005. By the early 21st century, pawnshops generated a turnover of S$1.1 billion. The Chinese account for more than 90% of pawnbrokers in Singapore. Among them, more than 85% are run by Hakkas, with those from Dapu County in China’s Guangdong province accounting for three-quarters of the group, and a small number coming from other centres for Hakka culture such as Meixian, Fengshun, and Yongding.

Dominating the Chinese medicine industry

Apart from pawnbroking, the Hakkas also dominated the Chinese medicine industry. This was thanks to the Eng Aun Tong Medical Hall established by Hakka entrepreneur Aw Boon Haw (1882–1954), whose successful Tiger Balm foray into the Southeast Asian market helped fuel the growth of Chinese medical halls. According to figures from the 25th Anniversary Commemorative Magazine of The Nanyang Khek Community Guild (renamed Nanyang Hakka Federation in 2020), there were over 160 Chinese medical halls run by the Hakkas before Singapore’s independence. Post-independence, the Hakkas operated as many as 300 Chinese medical halls at one point.

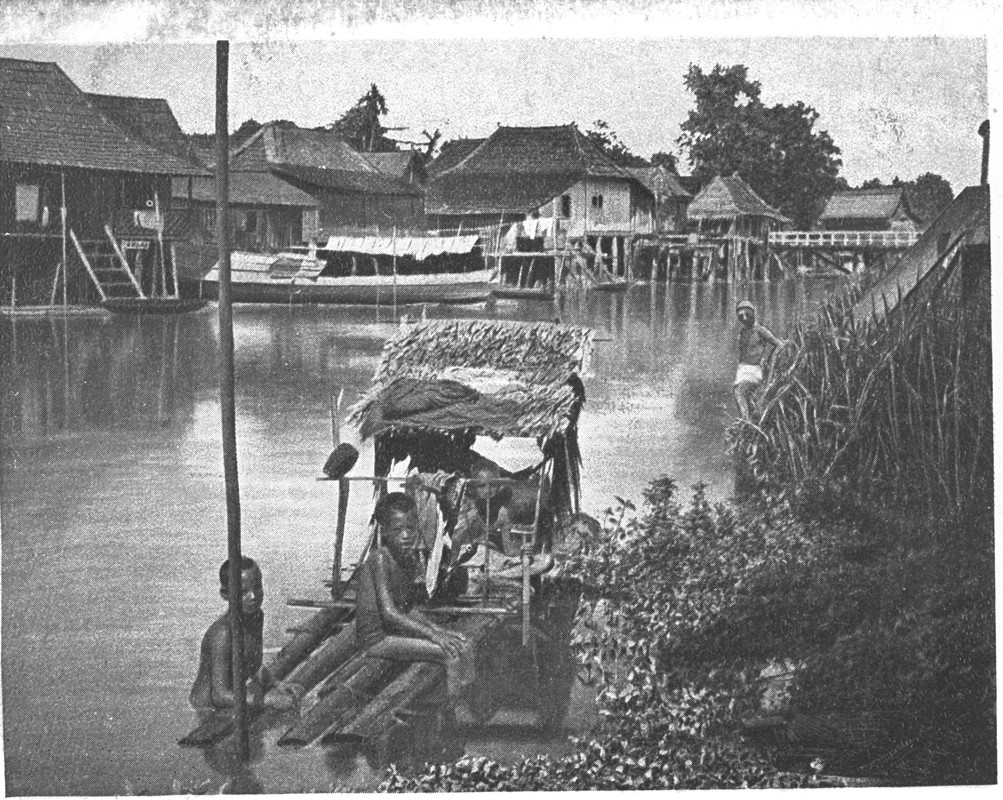

The Hakkas on Pulau Tekong

In the early 20th century, the British colonial government started planting rubber trees in Malaya, and the sparsely populated Pulau Tekong became another site for rubber plantations. It was during this period that the island saw a large influx of Chinese, with the Hakkas (from Dapu, Jiaying, and Fengshun in Guangdong) accounting for more than 60% of them. The Hakkas on Pulau Tekong mainly worked in agriculture, particularly rubber plantations.

A Hakka folk song composed by Chin Sit Har (1917–1988),3 an elder on Pulau Tekong, reflects how the Hakka community on the island at that time made a living:

“Rubber tapping at five in the morning, before breakfast at eight o’clock,

Rubber tapping should be done by ten-thirty, and we will pick up firewood on the way home.

Just when 80% of the task is completed, the sky turns dark and clouds fill the sky,

Wind howls and rain pelts down, half a day of hard work earns us nothing.

Unable to tap rubber on a rainy day, we mix porridge with salt water for breakfast,

With no money to buy rice, we pick wild vegetables and tighten our belts, waiting for tomorrow to come.

When we can’t tap rubber we grow crops, and eat sweet potato and tapioca with luffa.

If we all work together, we won’t need to buy food and can support our families.

Rubber tapping followed by crop farming, with hoes in our hands we open up wasteland,

Rain or shine we work hard, growing various crops in the hills.

We remove weeds and fill the hills with crops and vegetables,

When the rainy season comes, we consume dried food; fear not, we have food stocked up.

Rubber tapping in the morning and studying in the afternoon…”

In trade-oriented Singapore, the jobs and economic sectors open to the Hakkas were limited as they had arrived later. Nevertheless, through their own efforts, the Hakkas have not only achieved remarkable success in pawnbroking, but also made significant contributions to society in areas such as the Chinese medicine industry and rubber planting.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡客家人的传统行业. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | According to the 1957 Census of Population, the Chinese population in Singapore was 1,090,596, with more than 500,000 being Hokkiens and only about 78,000 were Hakkas. See Report on the Census of Population 1957, 146. |

| 2 | Yong Ching Fatt, Tan Kah-Kee, The Making of an Overseas Chinese Legend, translated by Li Fachen (Singapore: Global Publishing, 1999), 10. |

| 3 | See Chin Sit Har, oral history interview by Tan Beng Luan, 26 January 1988 to 15 March 1988, audio, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000882), Reel/Disc 1–24. |

Chen, Poh Seng and Lee, Leong Sze. A Retrospect on the Dust-Laden History: The Past and Present of Tekong Island in Singapore. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2012. | |

He, Qianxun. Xinjiapo diandang ye zongheng tan [Pawnbroking in Singapore]. Singapore: Char Yong (Dabu) Association and Singapore Pawnbrokers’ Association, 2005. | |

Hsiao, Hsin-Huang, ed. Dongnanya kejia de bianmao: Xinjiapo yu malaixiya [The changing face of Hakkas in Southeast Asia: Singapore and Malaysia]. Taipei: Research Center for Humanities and Social Sciences, Academia Sinica, 2011. | |

Lee, Leong Sze. Yi ge xiaoshi de juluo: Chonggou xinjiapo deguangdao zou guo de lishi daolu [A disappearing settlement: Reconstructing the historical path of Singapore’s Pulau Tekong]. Singapore: National University of Singapore’s Department of Chinese Studies, 2009. |