Living with civilisations: Southeast Asia’s local and national cultures

“Civilisation” and “culture” are modern terms that came from Western Europe. Both concepts have been translated into various languages but are often used interchangeably in translation. How should “culture” be distinguished from “civilisation”?

Culture is what every group of people has shared because they developed it together and is something they identify as their very own. The groups range from a simple one like an isolated tribe to a sophisticated community that could establish strong states. The cultures could be agrarian or pastoral, settled or nomadic, literate or non-literate. They were likely to be ruled by chiefs, priests, princes, kings and even emperors or elected leaders. Because their people of all classes had lived together for long periods of time, their cultures, whether defined as ethnic or national, were likely to be resilient and distinct.

Civilisation, on the other hand, stemmed from efforts by visionaries, prophets and teachers to explain the universe and find the meaning of life on Earth. From a set of first principles, ideational and moral systems were constructed to uplift the lives of everyone beyond local cultures and identities. When such visions inspired the leaders of strong states and empires, those leaders could rise above their local cultures and use the idea of a common humanity to define a borderless civilisation under their care. Each would then seek to bring local states and cultures under their wing and act as an agent bringing civilisation to others.

The records and artefacts show that both the mainland and maritime peoples of our region, Southeast Asia, did not produce their own civilisations. Instead, they chose what they wanted from those they were in contact with — all of them ancient civilisations that have survived to the present day.

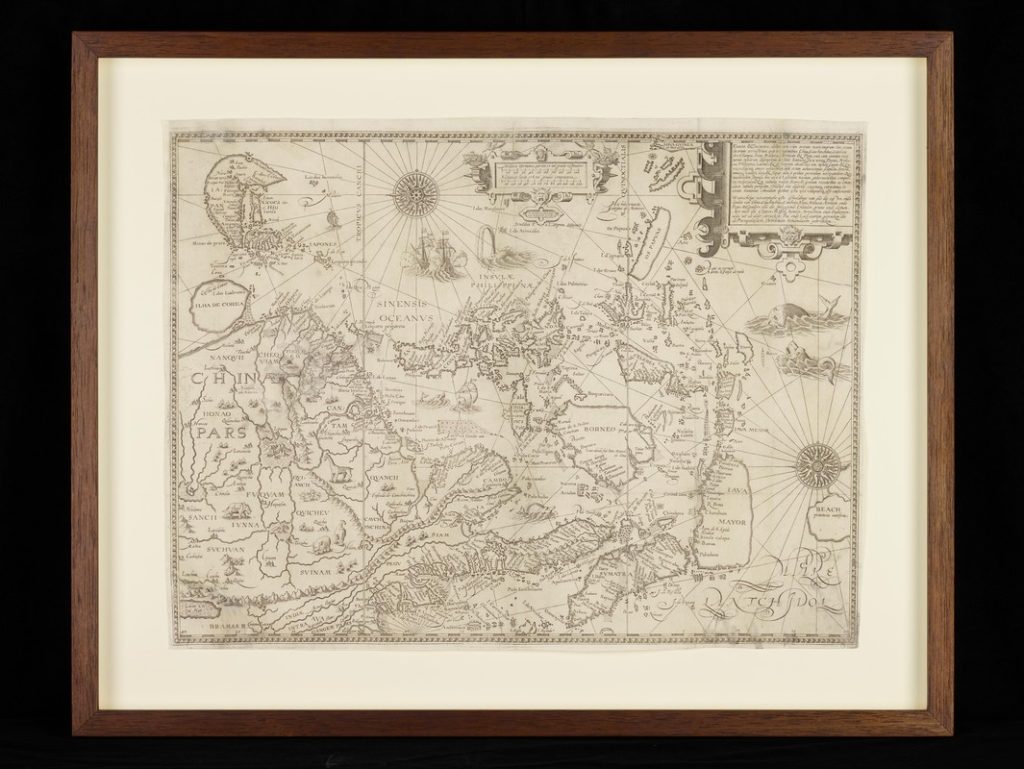

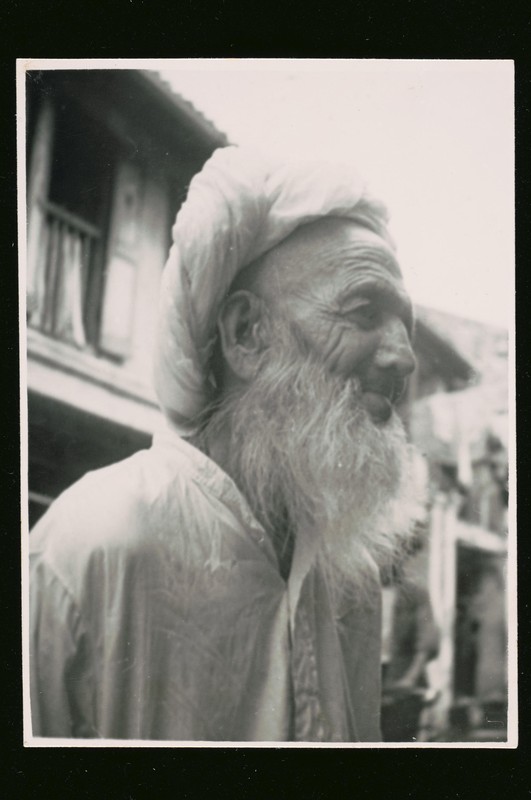

There was the Indic civilisation from the Indian subcontinent. There was the Sinic civilisation in China coming from overland as well as from the South China Sea. And further west, there was the Mediterranean civilisation from across the Indian Ocean. This civilisation was later identified with a monotheistic faith that produced a profound division, branching into the Islamic and Christian faiths. The Arabic-based Islamic merchants reached our region early while the European crusaders and trading companies arrived only after the 16th century.

Major changes followed the 18th century when the Age of Enlightenment in Europe led the world to the idea of modern civilisation.1 A new Singapore emerged out of the imperialist rivalries that mapped a region at the end of World War II, which the British called Southeast Asia. That region became one in which new nations were built and local cultures were being shaped into national cultures.

Civilisations: Indic, Sinic, and Islamic

For the first thousand years of recorded history, our region was most responsive to Indic civilisation and adopted many elements of it to shape many distinct cultures. It grew deep roots because it seemed to have had comprehensive appeal, especially among the agrarian peoples of mainland Southeast Asia. Even when the local peoples established links with the Sinic or Chinese civilisation to the north, what they found they had in common was their devotion to the Buddhist worldview that came from India. The civilisation’s deep and rich cultural roots spread across the subcontinent, and its spirit of ideational and aesthetic inclusiveness enabled the civilisation to withstand external threats, first from the Islamic conquerors and later from the British Empire.

Indic civilisation was represented by people later described as Hindus who offered a distinct road to rebirth rather than visions of Paradise and Heaven. They focused on developing original and esoteric insights about life that most people in our region found attractive and inspiring. But their emphasis on rigid caste divisions did not take root. That is a clear example of how the countries in our region were selective in what they adopted into their local cultures.

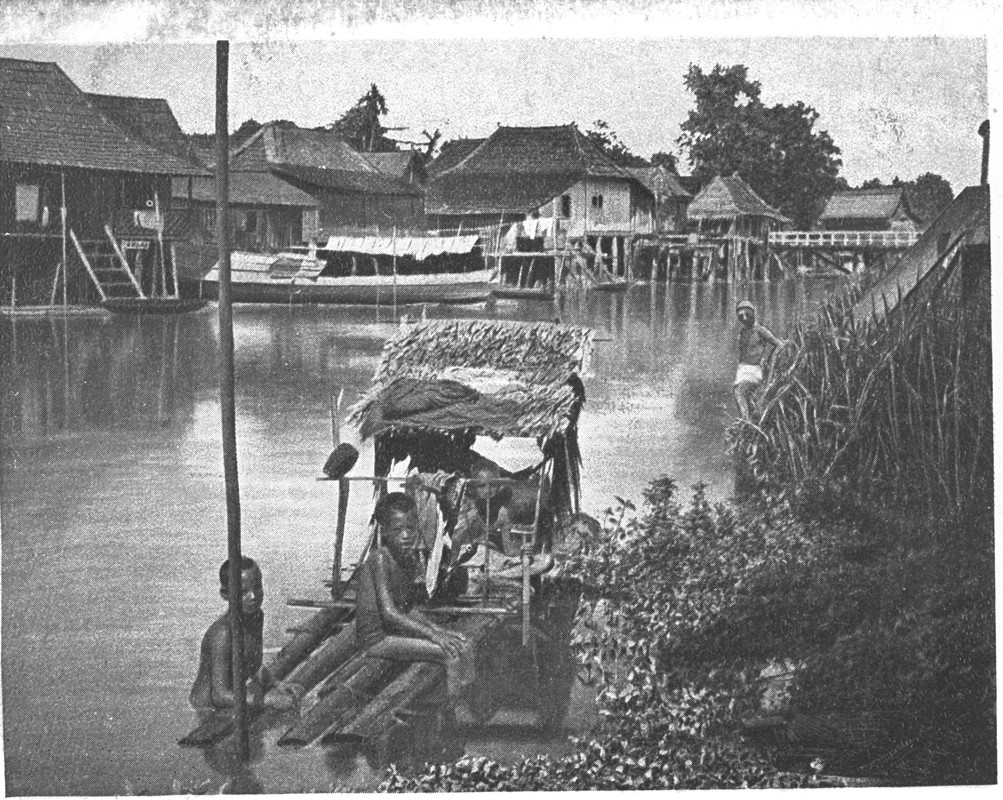

The people of Nusantara — the Indonesian archipelago — used their island world in different ways and kept their maritime trading activities distinct from that of earthbound mainland states. But both sides continued to develop their cultures by sharing the best of the Hindu and Buddhist manifestations of Indic civilisation. Neither the Khmers2 and their successors nor the archipelagic elites produced bold visionaries with independent worldviews that could have led to civilisations of their own. Both sets of states were content to shape their own respective cultures by selecting what they wanted from Indic civilisation.

Indic civilisation was the most attractive to both mainland and archipelagic parts of our region. Later trading developments brought the region close to a Sinic-cum-Indic Buddhist civilisation and then to the Islamic half of Mediterranean civilisation that came by sea. The core of the Sinic civilisation — unlike with the Indic and its outreach across the Bay of Bengal — was in North China far away from the maritime world of the Nusantara peoples. The Chinese themselves had first received their share of Indic ideas and institutions from missionaries who came overland from Central Asia and northern India. From them, the Chinese were won over by the subtleties of Buddhist dharma. Where relations with our region were concerned, it was not until large numbers of Chinese had migrated to the southern coastal provinces of China that maritime commercial activities quickly began to develop.

All of those who traded with the Chinese learnt to value their manufactures like silk and ceramics, and some of their trading methods and technological skills. But the political and cultural values of Sinic civilisation had little appeal to the Nusantara peoples who had been accustomed to an increasingly open multicultural environment. With the loose mandala system of state relations they took from Indic civilisation serving as a model, they had room to cultivate their own distinct local cultures.

On the mainland, the Khmer and Mon, the Thai and the Burmese consolidated their Indic heritage through their respective versions of Buddhist authority after that had been lost in India itself. When they later became nation-states, that internalised authority provided strong foundations for developing modern national culture. Similarly, the Vietnamese, probably the first proto-nation in our region, were developing a distinct national culture drawing primarily from Sinic civilisation. As for the archipelago peoples, their openness to all three of their neighbouring civilisations had enabled the local cultures on different islands and on the Malay Peninsula to retain distinctive features. This remained so even after most of its communities were later converted to Islam. Only those farthest to the east in the Philippines were later drawn into the Christian Mediterranean orbit but they too were inclined to maintain their own cultural features within that faith.

What began to make a difference was the growing importance of maritime power from the 16th century onwards. This power was shared between Britain and France during the 18th and 19th centuries. By that time, Southeast Asia was experiencing the early capitalist qualities of a modern civilisation that produced a decisive turn towards the idea of universal enlightenment.

Opening to the global maritime: The age of commerce

In the centuries leading to the 18th century, our region experienced what historian Anthony Reid (1939–2025) calls the “Age of Commerce”. From the perspective of civilisations and cultures, the period might also be described as the age of the fourth civilisation. It marked the growing presence of the Christian half of the monotheistic Mediterranean civilisation. That had been a constant rival to the Islamic half and was seen in our region as a separate civilisation. Coming with well-armed ships into the Indian Ocean, the Portuguese brought with them centuries of Catholic European hostility against their Islamic rivals. By that time, the Muslims in Asia, especially those of the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and the western coasts of India, were looking to the Ottoman Turks in Istanbul for leadership and were determined to respond violently in return. Their deadly struggles to represent their faith in the archipelago saw the Portuguese take over Muslim Malacca and then go on to control the Maluku Spice Islands.

Singapore was part of that struggle, especially when the Malaccan forces tried to defend their new base up the Johor River. After that failed and they moved south to the Riau-Lingga Archipelago — further away from Singapore — Singapore became merely one of the many ports that were affected by the wars that continued for the next two centuries. Merchants from the Indic and Sinic worlds continued to trade in Portuguese Malacca. The Orang Laut (“people of the sea”) and others in Singapore would have been aware of the civilisational conflict taking place around them, but they lived mainly with Nusantara Islam. That would have given them some sense of security because the civilisation of the caliphate,3 which was the headship of the Islamic faith, had by that time developed a large footprint on our region.

The enlightened modern

Two revolutions in the 18th century — the Industrial Revolution and the French Revolution — changed the course of history. Both were part of the Enlightenment civilisation and were the products of reason and humanism that had undermined church authority and the credibility of feudal and dynastic empires.

What enabled the Western European nations in the 19th century to dominate every corner of the world? They did so largely by occupying territory and building extensive empires. With their control of ports, colonies and protectorates, they obtained the natural resources needed to develop industries and markets in which their manufactures could replace those that were locally made. By doing so, they saw themselves as modern and civilised — people ready to help the natives escape their ancient and backward civilisations.

Southeast Asia was becoming the frontier zone of the two kinds of power that stood for Europe’s modern civilisation in Asia. One was Bourbon France supporting a state-centred economy, and the other was the English and Dutch East India Companies backed by parliaments committed to free trade. Their rivalry in the Indian Ocean was intense and ended with British victory. The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824 marked the national-imperial border along the Straits of Malacca that, over 120 years later, divided Malaysia and Indonesia into two modern nation-states.4It is sobering to think that our region became part of one of the most powerful political constructs in history when national empires claimed to represent modern civilisation.

Thus developed the idea that the nation-state could harness the new Enlightenment civilisation in its enterprise to lead the world to progress. Their mission was not merely to expand power and wealth and take territory, but also to bring modernity to the benighted races and put an end to the old empires still clinging to their feudal and dynastic ways.

It was Enlightenment civilisation that connected modernity with progress and paved the way for a world of nation-states. The idea of becoming a nation is not new. It has an ancient history going back to when some sense of identity was shared by a multitude of tribes of common descent. But the right of such nations to become sovereign states became possible only after the Treaty of Westphalia of 1648.5 In the world of new national consciousness, the colony of Singapore stood out as a city whose people of various origins used the city as a centre for their activities between land and sea before deciding to make it their base or home. The authorities who were determined to make the free port a success encouraged the acts of merantau (wandering) that swelled a population with the characteristics of a plural society.6

Having long lost its place as a political centre, Singapore did not have a distinctive local culture. From a barely populated part of the Johor Empire, it started afresh to become part of the Straits Settlements governed from India. Even after it became a separate colony, it was primarily a link in the British imperial chain that was used as a business hub mainly by peripatetic Malays, Chinese and Indians. Most of them brought their cultures with them, cultures inspired by the Indic, the Islamic and the Sinic.

When European imperialism reached its heyday just before World War I, British Malaya was conceived with its centre in Singapore. That Malaya was what the island city would become part of when the war ended in 1945. As with the rest of Southeast Asia, this Malaya conformed to the regional norm of having an imperial administration and distinct local cultures shaped by the living civilisations that were brought there by its various communities.

A divided enlightenment world

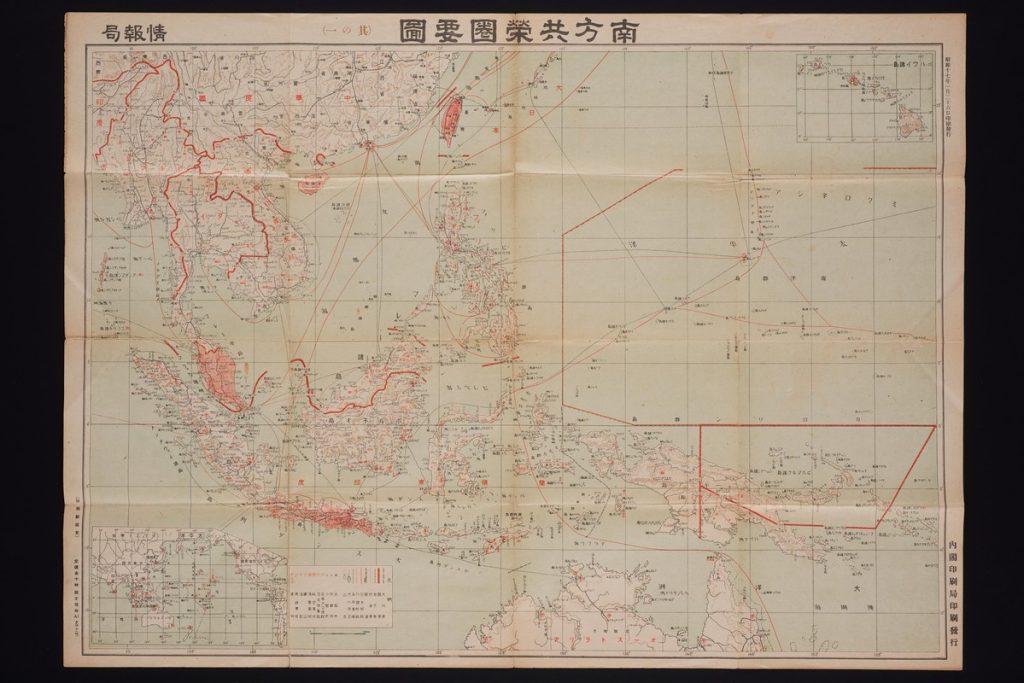

The catalyst for a new world order was the war fought by an Asian power — imperial Japan. The Japanese claimed to have liberated our region from Western colonialism and that helped to reveal the fatal weakness in that Enlightenment civilisation. They also tried to prepare the Philippines, Indonesia and Burma for possible nationhood. At the same time, Japan demonstrated how their response to Enlightenment modernity had helped to strengthen Japanese national culture. This had encouraged local nationalist leaders to make every effort to resist the colonial powers that tried to return.

As the weakest of those powers, the Dutch found that they could not subdue the nationalists who embarked on a revolutionary war and insisted on keeping all of the Netherlands East Indies as the Republic of Indonesia. The French, facing three potential rival nations in their “Indochina”, hoped to prolong their presence. When the Cold War came to the region after Nationalist China fell to the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), the United States encouraged the French to resist Vietnamese demands for an independent nation-state. The British, recognising the need to leave India, let Burma go free, focusing instead on retaining Malaya, Singapore, and scattered ports and islands.

The European empires redrew national borders, the most important being those identified by British strategists which defined Southeast Asia as a distinct region separate from China and India. That way, Southeast Asia could provide a separate theatre for future political and military operations. This reflected the wider rethinking that sought to find a new geopolitical framework that would enable powerful countries to settle their conflicting interests and help to bring peace to the world.

During World War II, the victors led by the US, Soviet Union and Britain agreed that the aggressive national empires had undermined the Enlightenment Project, which they still saw as progressive and reformable. That would require making major corrections to the civilising mission to stop powerful nation-states from fighting one another again. The chastened powers thus tried to reinvent themselves. The British and the French maintained their spheres of influence by tying former colonies to a nominal commonwealth of nations, aiding their transition to nation-states. But they were aware that the modern world would no longer tolerate national empires and that other civilisations were modernising to challenge Western dominance.

From the 1950s, the US and the Soviet Union were virtual empires, each with “security partners” that fought through their proxies. In our region, that was done via a hot war in Vietnam. After the eventual collapse of the Soviet Union, the US became the world’s sole super nation-state. As victor of the ideological war, it saw itself as the beacon for universal values and the guardian of global civilisation.

Southeast Asia benefitted from the peace that ensued. The region’s self-discovery four decades earlier had enabled it to appreciate how its local cultures had grown in confidence by learning from neighbouring civilisations. They continued to do that even under Western rule.

Southeast Asia: A modern region

Two developments encapsulated the process of re-education that also helped to shape the region’s understanding of its common interests. The first was what our leaders experienced at the Bandung Conference of 1955.7 The other was what they managed to learn when they turned a half-ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) into the full 10-member organisation it now is.

The Bandung Conference’s declared purpose was to bring together those members of the UN who were opposed to the world being divided between two antagonistic blocs represented by the Warsaw Pact states and those in the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). Of the 29 nations that attended, eight represented Southeast Asia: North and South Vietnam, as well as six others that were already independent – namely Thailand, the Philippines, Laos, Indonesia, Burma, and Cambodia.

The Bandung spirit showed that — although proud of their civilisations — all the new nations aspired to become modern. It also showed that it was unable to influence the course of the Cold War. Nevertheless, it provided an indication that Southeast Asia could become an active player in global affairs even when conditions were so difficult.

ASEAN had a modest beginning amid the Vietnam War. Its founding five members included the newly independent Republic of Singapore. It could do little to affect the course of the hot war nearby that the US was losing. Each could therefore concentrate on nation building and reshaping their complex societies. Both Malaysia and Singapore were undergoing a painful process of virtual decoupling. The new city-state Singapore had the challenging task to build its plural society into a secure and prosperous nation-state.

All five ASEAN countries had one other thing in common. Each was committed to becoming modern in as many ways as possible while defending the country’s mix of local cultures. The nationalist leaders were very aware that they also had powerful protectors in the US and its allies against those who sought to overturn the established order in the name of people’s revolution.

Living with civilisations

In the development of ASEAN, the cultural responses of its members to modernisation are all founded on common aspirations to build nation-states. These cultural responses can be grouped as follows. For Indonesia, Malaysia, and Brunei, the links with their Islamic Ummah have grown stronger.8 Similarly, the links of most Filipinos with their Christian and trans-Pacific co-regionalists remain firm despite the distances involved. A common faith continues to connect Thailand, Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia to countries that have large numbers of Buddhist believers. As for Vietnam, it has retained its Sinic culture through a shared history of recent revolutions. And then there is Singapore with its majority of citizens of Chinese origins having obvious links with modern Sinic civilisation.

The leaders of Singapore, an unexpected nation-state, embraced its modern administrative and legal heritage, and expanded the range of its imperial economic connections. Singapore saw the UN organisation as the embodiment of a renewed Enlightenment civilisation. This protected sovereign nation-states wherever located and however small. With this shield, the island-state could nation-build with a plural society that drew from several living civilisations.

Given Southeast Asia’s history of local cultures selecting what they needed from the civilisations they encountered, Singapore’s best interests seems to be to support the common aspirations of all member states of our region. What the new nation-states had chosen to learn were qualities that were borderless, those not identified with any national political system. Having done that for centuries, each ASEAN member had become confident in dealing with unpredictable conditions. In that way, each has been able to strengthen its local cultures and shape its own modern national culture. Singapore as a state has chosen to stay with this common experience. It is committed to the idea that its citizens of whatever origin should respond only to borderless civilisational appeals and not to nationalist ones. Singapore’s modern culture would require its leaders to try their hardest to keep the national and the civilisational clearly differentiated. This would ensure that Singaporeans of Chinese origin would be able to act in ways that the whole ASEAN community can understand and be comfortable with. That would show how a modern nation-state could, as with cultures in the past, co-exist with a variety of living civilisations.

| 1 | The Age of Enlightenment was a philosophical movement in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries, which believed in the use and celebration of reason, the power by which humans understand the universe and improve their own condition. |

| 2 | The Khmers refer to an ethnic group native to Cambodia. |

| 3 | A caliphate is a territory ruled by a caliph, an Islamic ruler. |

| 4 | The Anglo-Dutch Treaty of 1824, also known as the Treaty of London, was primarily a settlement of a long period of territorial and trade disputes between Great Britain and the Netherlands in Southeast Asia. The treaty redefined the spheres of influence of these two colonial powers in the region, eventually leading to the formation of British Malaya and the Dutch East Indies. |

| 5 | The Treaty of Westphalia ended decades of war in Europe. Some scholars of international relations credit it with providing the foundation of the modern state system and articulating the concept of territorial sovereignty. |

| 6 | Merantau, practised by the Minangkabau people in Indonesia, refers to a kind of wandering where the wanderers, after years of seeking experiences, expect to return home. |

| 7 | The Bandung Conference, also known as the Asia-Africa Conference (AAC), was held in Indonesia’s Bandung on 18 April 1955. It was a meeting of 29 Asian and African nations, what is known as Global South, that sought to draw on Asian and African nationalism and religious traditions to forge a new international order that was neither communist nor capitalist. For more information on the historical significance and legacy of the conference, refer to See Seng Tan and Amitav Acharya, eds. Bandung Revisited: The Legacy of the 1955 Asian-African Conference for International Order (Singapore: NUS Press, 2008). |

| 8 | Ummah refers to the whole community of Muslims bound together by ties of religion. |

Chan, Ying-kit and Hoon, Chang-Yau. Southeast Asia in China Historical Entanglements and Contemporary Engagements. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022. | |

Ho, Elaine. Citizens in Motion: Emigration, Immigration, and Re-migration Across China’s Borders. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018. | |

Kuhn, Philip A. Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times. Singapore: NUS Press, 2008. | |

Wang, Gungwu. China and the Chinese overseas. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Dongnanya yu huaren: Wang Gengwu jiaoshou lunwen xuanji [Southeast Asia and the Chinese: Selected papers of Professor Wang Gungwu]. Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company, 1987. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Living with Civilisation: Reflections on Southeast Asia’s Local and National Cultures. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2023. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Luhaizhijian: Dongnanya yu shijie wenming [Between land and sea: Southeast Asia and world civilizations]. Translated by Wan Zhijun. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 2025. | |

Wang, Gungwu. The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000. |