Chinese calligraphy in Singapore through the years

Calligraphy was traditionally an integral part of Chinese education. Part of daily life, it was used in public and private correspondence, records, and bookkeeping. Most Chinese schools in Singapore from the early 20th century to the 1970s therefore ran calligraphy classes.

Calligraphy activities before World War II

The Chinese in mid-19th century Singapore recognised the importance of education. Generally speaking, the curriculum of early Chinese schools “still followed the old Chinese tradition, teaching little beyond the Three Character Classic, Thousand Character Classic, Youxue qionglin (The primer for traditional Chinese culture), the likes of Four Books and Five Classics, as well as calligraphy and zhusuan (knowledge and practice of performing arithmetic calculations using an abacus)”.1 Similarly, the teaching of calligraphy in traditional private schools was mainly for practical purposes. For example, the account books used by the early Chinese business houses were usually neatly written in Chinese brush and ink, in two variants of the regular script — gongkai and xingkai.

In the early 20th century, the scholar Khoo Seok Wan (1874–1941), known as nanqiao shizong (“master poet of southern overseas Chinese”), had a circle of friends who were mostly literati, academics, artists and politicians from the late Qing period. Of the many different forms of written expression, they chose calligraphy as their medium for inscribing prefaces and postscripts on each other’s paintings or collected artworks, for exchanging complimentary verses, and even for exploring ideologies and debating politics. Meanwhile, art collector Huang Man Shi (also known as Huang Cong or Huang Mun Se, 1890–1963), had a coterie of literati, artists and intellectuals who had received a modern education. His studio Bai Shan Zhai was an important salon in Singapore at the time.2 The people in Khoo and Huang’s circles represented the middle and upper classes of Chinese society. Besides interacting with each other, the groups also had some members in common. Generally speaking, Huang’s circle was more active than Khoo’s in promoting the development of local calligraphy. 3

As large numbers of Chinese immigrants sailed south at the end of the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th century, clan associations and Chinese temples were established in Singapore. In keeping with Chinese tradition, these buildings had plaques or couplets inscribed by distinguished people. In parts of Singapore where there is a lot of traditional architecture, this offers a feast for the eyes even today. One example of this is Thian Hock Keng Temple, built in 1839 on Telok Ayer Street. Above the main hall, there is a plaque bearing the characters bo jing nan ming (calm waves on the south sea) in the hand of Emperor Guangxu. Over at Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery, which was founded in 1898, the calligraphy on plaques and couplets are from distinguished figures of the past century. These inscriptions were not merely instructive — they also added a touch of beauty to the monasteries. At clan and guild associations, plaques inscribed by well-known modern calligraphers from China are also a common sight. The plaques or couplets in these locations, including any ink works hung on display, do not just illustrate – they also form an important part of local Chinese visual art heritage.

Newspapermen, calligraphers and painters from Southern China

For an artistic style representative of the era to emerge, members of the literary and artistic community need to create works, develop their calligraphy skills, and pass them on. Media coverage will also help it enter public consciousness. During the pre-war period, some important journalists who were also calligraphers and painters included Yeh Chih Yun (1859–1921) and Zhang Shu’nai (1895–1939). Yeh Chih Yun, who was editor-in-chief of Lat Pau for 40 years, was well-versed in calligraphy and painting, seal cutting and traditional Chinese medicine. After arriving in Singapore in 1919, Zhang Shu’nai took up a post as lead writer and editor-in-chief of Sin Kuo Min Press. He was also an early advocate of xin wenxue (new literature), and many plaques belonging to local shops were created by him. Other important figures promoting the art of calligraphy were calligraphers and painters who had travelled south to exhibit their art or make a living. Among them were Pan Shou (1911–1999), Lim Hak Tai (1893–1963), Ng Here Deog (1910–1994), Ho Hsiang-Ning (1878–1972), Xu Beihong (1895–1953), as well as the brothers Gao Guantian (1876–1949) and Gao Jianfu (1879–1951). After the 1937 Marco Polo Bridge Incident, more scholars and artists also headed south. Prominent names were See Hiang To (1906–1990), Liu Yanling (1894–1988), Liu Haisu (1896–1994) and Yu Dafu (1896–1945). They either stayed for a short period or became citizens after Singapore’s independence. All of them contributed to the development of calligraphy in Singapore.

Post-war calligraphy education in Chinese schools

During the period after World War II, Chinese education in Singapore was well-developed. There were once over 300 Chinese primary and secondary schools on the island in the period from pre-war to the 1980s, before the education policy changed. Among them, several prominent Chinese institutions such as Tuan Mong School and Chung Cheng School had no lack of calligraphers among their teaching staff. This included Tan Keng Cheow (1907–1972) and Chan Shou She (1898–1969), who championed calligraphy education in their respective schools. Students who were talented in calligraphy emerged in waves from both schools, and often came tops in competitions, be it in the primary or secondary school categories. Many of the calligraphers nurtured by Tuan Mong and Chung Cheng have become active calligraphers in Singapore since the 1980s. Tan Siah Kwee, who heads the Chinese Calligraphy Society of Singapore, for example, is a Chung Cheng graduate. The society co-hosts a couplet-writing (hui chun) calligraphy competition with community clubs every Lunar New Year to promote the development of calligraphy in Singapore — allowing it to reach the general public and become a popular art.

In addition, Chen Jen Hao (1908–1976), who was the principal of Dunman Government Chinese Middle School (now Dunman High School) from 1956 to 1969, had always attached importance to the influence of calligraphy on students. After it became a Special Assistance Plan (SAP) school, calligraphy remained part of its curriculum. One former student who studied under Chen is the local calligrapher and painter Koh Mun Hong.

Keeping the art of calligraphy alive

Since the 1960s, a growing number of calligraphers have imparted their craft via private lessons. Calligraphers who had done so over the years include See Hiang To and his students Tan Kian Por (1949–2019), Tan Kee Sek and Teo Yew Yap; as well as Pan Shou, Chang Kwang Wee, Koh Mun Hong, Chang Sow Yam, Choo Thiam Siew and Wong Joon Tai. After the 1990s, new immigrants who were talented in calligraphy also added vibrancy to the local scene. Among them are notable names such as Guo Shuming, Ma Shuanglu and Kong Lingguang.

When Singapore’s economy grew rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s, Singaporeans enjoyed greater spending power. More shops selling wenfang sibao (“four treasures of the study”) started to spring up. At the time, people looking for brushes, ink, paper and inkstones had more options besides Chung Hwa Book Company, The Commercial Press Agency, and Shanghai Book Company. They could also head to places such as Tsing’s Book & Art (Jinshi Shuhuashe), Si Bao Zhai Arts Gallery and Chen Soon Lee Book Stamp and Coin Centre in Bras Basah Complex (dubbed the “book city”). In the 1970s, Chung Hwa Fine Art Gallery — located on the fourth floor of Chung Hwa Book Company in the South Bridge Road area – would hold a yaji (literati gathering) every Saturday afternoon. Many regaled stories of how Pan Shou, surrounded by a crowd, would pick up his brush, dip it in ink, and complete a piece of work in a flash — whether it was a banner, couplet, fan, or zhongtang (calligraphy hung centrally in a hall).

After changes to Singapore’s education policy in the 1980s, English became the medium of instruction in schools, and Chinese was relegated to a single subject. However, various community clubs and associations have continued to be active in organising calligraphy competitions. The Chinese Calligraphy Society of Singapore, community clubs, Nanyang Calligraphy Centre, Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal Carving Calligraphy & Painting Society, and Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, conduct calligraphy courses, providing more avenues for the many people interested in learning calligraphy.

Calligraphy exhibitions in Singapore

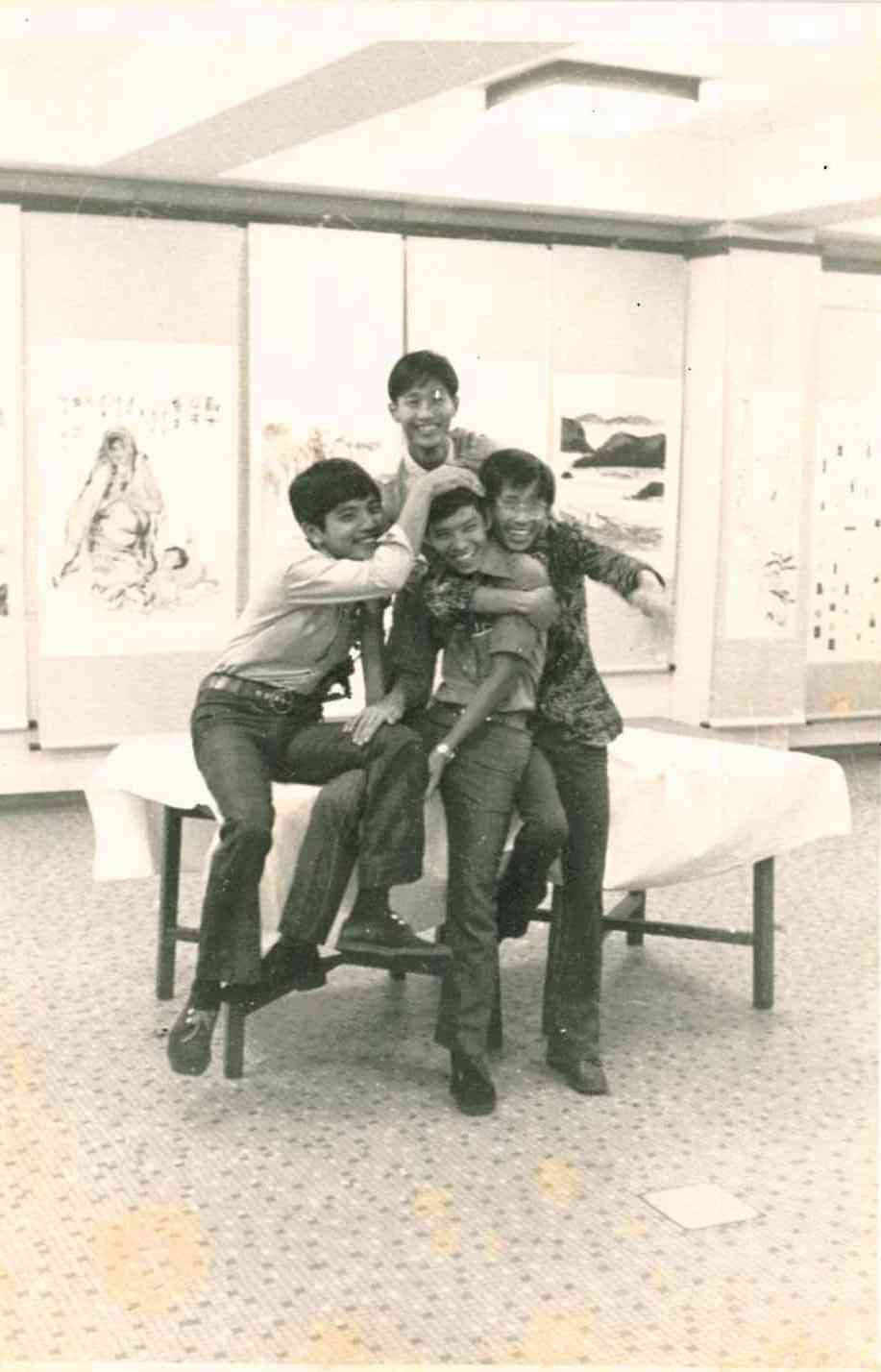

Since 1969, Singapore’s National Day Art Exhibition has been an annual feast for the eyes. From the 1970s to 1980s, it was a platform for the first and second generation of calligraphers in Singapore to exhibit their works. Prominent local art associations such as the Society of Chinese Artists, Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal Carving Calligraphy & Painting Society, and the Chinese Calligraphy and Art Research Society (predecessor of the Chinese Calligraphy Society of Singapore) hold numerous calligraphy and painting exhibitions.4 More recently, calligraphy and painting groups such as the Hwa Han Art Society, Molan Art Association, Lanting Art Society have also become a driving force in the development of local calligraphy.

In the 1980s, when Singapore’s economy took off, there was a growing trend among Hong Kong and Taiwan calligraphers and painters to hold exhibitions in Singapore to sell their calligraphy and paintings. At the start of China’s reform and opening-up, some antique shops or galleries in Singapore were also very active in inviting modern Chinese calligraphers and painters to exhibit in Singapore. This triggered a wave of interest in collecting Chinese calligraphy and ink paintings, as well as in learning calligraphy.

Since 2000, prominent annual calligraphy exhibitions in Singapore such as the Singapore Book Fair, Shicheng Moyun calligraphy exhibition, the National Day Calligraphy & Painting Exhibition hosted by Ngee Ann Cultural Centre, and Nanyang Calligraphy Exhibition, have transformed learning calligraphy into a trend in self-cultivation. From teenagers to the middle-aged and elderly, many have taken the bold step of participating in calligraphy exhibitions.

Looking back on the developments of the past decades, it can be said that despite the closure of Chinese-medium schools, the calligraphy scene in Singapore continues to be vibrant and alive.

This is an edited and translated version of 书法艺术在新加坡的传承与发展. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Kua Bak Lim, “Chongwenge yu cuiying shuyuan” [The Chongwenge and Cuiying school], in Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat], edited by Lim How Seng et al. (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1975), 217–219. |

| 2 | According to See Hiang To, Huang Man Shi once remarked, “You really don’t find any commoner coming in and out of my Baishanzhai.” See See Hiang To, “Baishanzhai tanwang” [Reminiscences of Bai Shan Zhai], in Huang Manshi jinian wenji, edited by Huang Shufen, 36. |

| 3 | Huang Man Shi motivated and promoted local calligraphers and painters considerably. For example, he once sold calligraphy and paintings on behalf of the painter Chen Yashi, who was more than 70 years old at the time, to help him cope with the difficult life during the Japanese Occupation; in 1946, when calligrapher Tsue Ta Tee (1903–1974) visited him in Singapore from Bangkok, Huang Man Shi encouraged him to hold a calligraphy exhibition and personally attended to the details. See Ma Jun, “Lunxian shiqi de manlao” [Grandmaster Mun during the time of the Japanese Occupation], in Huang Manshi jinian wenji, 70–71. |

| 5 | Maituo xinjiyuan: Zhonghua meishu yanjiuhui qishi zhounian jinianji [Towards opening up a new era: The Society of Chinese Artist 70th anniversary commemorative issue] (Singapore: The Society of Chinese Artist), 19–20. After the independence of Singapore, the society, in 1966, held a calligraphy exhibition of distinguished personages; in 1969, a Huang Jai Ling calligraphy, painting and seal engraving exhibition was held; in 1972, another calligraphy exhibition of distinguished personages was held; in October 1976, 216 stele rubbings collected by See Hiang To was displayed at a local calligraphy exhibition; in 1977, an exhibition of the works by distinguished calligraphers and painters from the Ming-Qing period was held; in August 1978, a calligraphy symposium was held featuring Pan Shou, Huang Pao Fang (1912–1989), Wong Kok Liang (1920–2004), See Hiang To, Zhuang Shengtao and Tan Siah Kwee among others; and in 1981, a Jao Tsung-I (1917–2018) calligraphy and painting exhibition was held. In addition to the above, the annual exhibitions held by Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal Carving Calligraphy & Painting Society since 1973 have also contributed to the local calligraphy scene. Established in 1968, the Chinese Calligraphy and Art Research Society has held many international calligraphy exhibitions since 1990; and there is also the Singapore-Japan calligraphy exchange exhibition, the Singapore-China calligraphy exchange exhibition, the Singapore-Taiwan calligraphy exchange exhibition, the Singapore-Malaysia calligraphy exchange exhibition, the Singapore-South Korea calligraphy exchange exhibition, and the Singapore-Hong Kong calligraphy exchange exhibition, all of which have played an important role in promoting and popularising calligraphy art. |

Huang, Shufen, ed. Huang Manshi jinian wenji [Collected essays in commemoration of Huang Man Shi]. Singapore: South Seas Society, 1977. | |

Ler, Chin Tuan. “Sanwei mingshi zao jiu le wo” [Three great teachers made me who I am]. Nanan Arts & Culture. Singapore Lam Ann Association. | |

Tan, Puay Hock. Xia chong yu bing ji [Summer insect talking about ice anthology]. Singapore: City Book Room, 2022. |