Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng: The cemetery built by the Cantonese in Singapore

The Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng cemetery, with its entrance at Upper Thomson Road, covered an area of 324 acres in the past, equivalent to more than 180 football fields. In the early 1980s, that land was used by the government to develop the new town of Bishan. Today, about two-thirds of the flats in Bishan sit on what was originally the cemetery.1

Just like all other Chinese cemeteries, Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng represented the Chinese community’s belief in being self-reliant in a foreign land — in this case, by taking care of the funeral rites of fellow clan members. Clan associations established 290 collective tombs (zongfen) within the cemetery, which were organised around kinship, place of origin in China, or occupation, and held ceremonies during the annual Qing Ming and Chong Yang festivals.

Before Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng, some of the existing cemeteries serving the Cantonese and Hakka community were Cheng San Teng in the area near Maxwell Market, and Loke Yah Teng in Bukit Ho Swee. The establishment of Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng was initiated in 1870 by a group of people. One of them was Boey Nam Sooi, who pooled resources with people from the prefectures of Guangzhou, Huizhou and Zhaoqing. The aim was to purchase land for the burial of Guang-Hui-Zhao people who had “found their way here to Selat (Singapore) and died of unfortunate and ill-fate in a foreign land”.2

Inscription records reveal that the organisation and management of Peck San Theng (as the cemetery was known for short) matured progressively after 20 years of efforts. Members of the Boey (Mei) family, including Boey Nam Sooi, Boey Ah Sam, Mei Wang, and Mei Duancheng, as well as the “Seven Shops of Market Street”, namely Choo Kong Lan, Choo U Lan, Choo Foo Lan, Loh Kee Seng, Kwong Hang Ho, Loh Chee Seng, and Tong Tak Ho, made large donations for the construction of temples and roads.3Hoo Ah Kay (1816–1880), a native of Panyu who served as the consul for China, Russia, and Japan in Singapore, appealed to the colonial government for land tax exemption. Boey Ah Sam, the “General Manager” (da zongli) of Peck San Theng’s developments, was appointed as one of the first members of the Chinese Advisory Board along, with others such as Tan Keong Saik (1850–1909), Tan Jiak Kim (1859–1917), and Seah Liang Seah (1850–1925).4

Peck San Theng in the 20th century

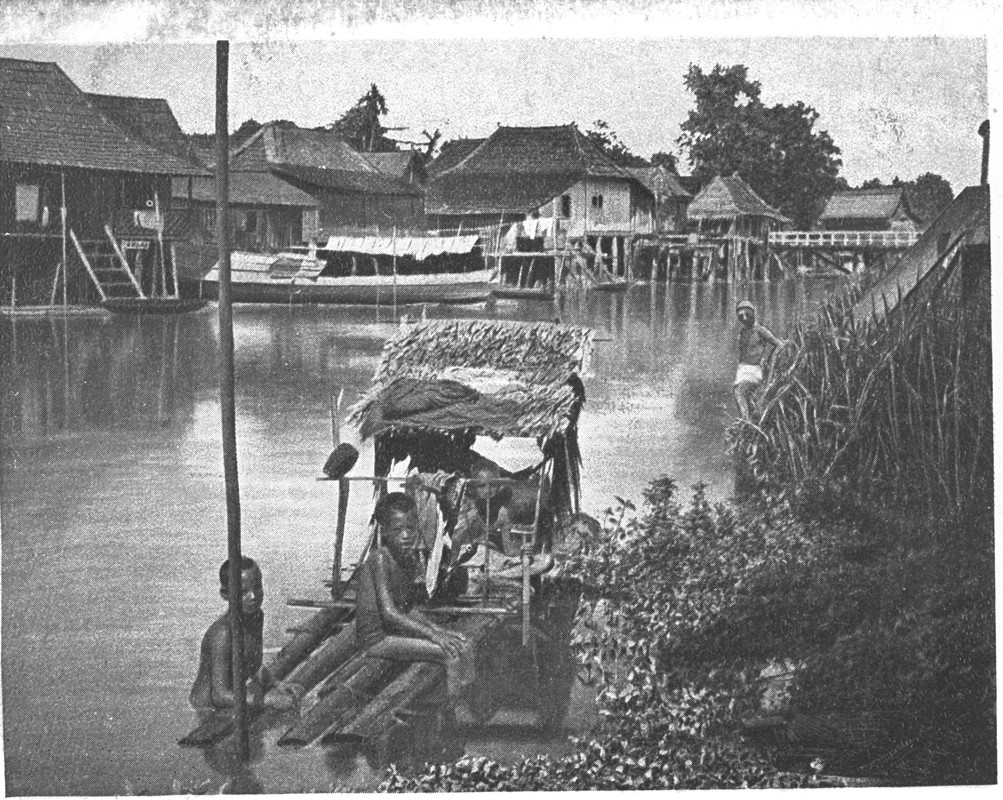

In the early 20th century, as the number of homes and shops in Kampong San Theng multiplied with the influx of immigrants from China, a cultural and economic ecosystem had begun to take shape. Peck San Theng, now jointly managed by 16 Cantonese clan associations, went on to set up Kwong Wai Shiu Peck Shan Ting School (1936–1981) next door, providing free education to children of all ethnicities. This helped create a community where people could live, work, and honour the dead in the same area.

In 1948, Peck San Theng acquired an additional 175 acres of land, and expanded to the largest size in its history. The burial grounds were demarcated by 12 pavilions which provided resting places for families who came to pay their respects. The 13 burial sites were named after the 13-word phrase “Xing Jia Po Guang Hui Zhao Bi Shan Ting Yu Lan Sheng Hui” (The Yu Lan festival of Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng in Singapore) as Xing Zi Shan, Jia Zi Shan, Po Zi Shan, and so on.5

Peck San Theng also collaborated closely with Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital to manage the funeral rites of deceased patients who had nobody to depend on. According to inscriptions found on the 1923 Grand Universal Salvation Ritual monument,6 Peck San Theng had already provided funding to the hospital then. And according to records from 1930, individuals at a Peck San Theng meeting — among them Ng Sing Phang (1873–1951), Au Min Tong (circa 1882–1939), Chan Chan Phang (unknown–1939), and Lum Mun Tin (1873–1943) — had voted to grant Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital’s request that a rubber plantation at the second pavilion be used to reinter, without charge, the remains of patients who had passed away at the hospital over the years.

Ng Sing Phang, a former general manager of Peck San Theng, was then the manager of Kwong Wai Shiu Hospital. Au Min Tong, Chan Chan Phang, and Lum Mun Tin were meanwhile board members and estate trustees of the hospital. These people also served in various other charity organisations, clan associations and schools.

A flagship Peck San Theng event is the “Grand Universal Salvation Ritual”. Notably, it was held during World War II in 1943, and after the explosion of the oil tanker Spyros at Jurong Shipyard in 1978, to offer salvation rituals for the deceased victims.7

When the cemetery had to be cleared in the 1980s, Peck San Theng retained eight acres of its land, the size of about five football fields, and became a columbarium for people of all races and dialect groups. A heritage gallery was established in 2018 to preserve the history of the Bishan and Cantonese cemeteries.8

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡广东人筹建和管理的坟山——广惠肇碧山亭. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Lee Kok Leong, ed., Bishanting lishi yu wenwu [The history and heritage of Peck San Theng]. |

| 2 | From an inscription soliciting donations for Peck San Theng in 1890, as transcribed by Lee Kok Leong at Peck San Theng. |

| 3 | Birth and death years of several persons are unknown. |

| 4 | Lee Kok Leong, Dayanji, yueyangren [Breaking the Waves] (Singapore: Traveler Palm Creations, 2017), 121–122. |

| 5 | Lee Kok Leong, ed., Bishanting lishi yu wenwu [The history and heritage of Peck San Theng], 94–107. |

| 6 | The Grand Universal Salvation Ritual is a ritual of salvation for the deceased that originated in the late Qing and early Republican era in the Pearl River Delta region, and which was later adopted by Peck San Theng in Singapore to promote filial piety by expressing gratitude and honouring one’s ancestors. It is usually held during the Chong Yang festival in the ninth month of the lunar calendar, where an altar is set up for Buddhist and Taoist priests to recite scriptures together and conduct salvation rituals such as “breaking hell” and “crossing the bridge of gold and silver”. The ceremonial event lasts for three days and three nights. |

| 7 | Zeng Ling, “Lishi shang de Wan Yuan Sheng Hui yu Bishanting de zijin laiyuan” [The Grand Universal Salvation Ritual in history and the funding sources of Peck San Theng], Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng’s Yang, No. 3 (June 1999): 2–3. |

| 8 | The establishment of the Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng Heritage Gallery was partially funded by the National Heritage Board of Singapore. See Lee Kok Leong, ed., Bishanting lishi yu wenwu [The history and heritage of Peck San Theng], 169–192. |

Guanghuizhao bishanting wanyuan shenghui tekan bianji weiyuanhui, ed. Guanghuizhao bishanting wanyuan shenghui tekan [Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng’s Grand Universal Salvation Ritual Special Issue]. Singapore: Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng, 1960. | |

Lee, Kok Leong, ed. Bishanting lishi yu wenwu [The history and heritage of Peck San Theng]. Singapore: Singapore Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng, 2019. |