Cantonese clan associations in Singapore

The clan associations of the Cantonese and other dialect groups in Singapore are historical products of the Chinese diaspora across different periods of time. At their height in the mid-20th century, approximately 290 Cantonese clan associations could be found on the island.1These organisations were formed based on the shared ties of kinship, place of origin in China, and profession, and had provided both practical and emotional support to immigrants (also known as sinkeh, or newcomers).

As a group, “Cantonese” refers to the Guang-Hui-Zhao (or Kwong-Wai-Siew) people whose mother tongue is Cantonese. In the Qing dynasty, the Guangdong province had 10 prefectures: Guangzhou, Huizhou, Zhaoqing, Chaozhou, Jiaying, Leizhou, Lianzhou, Gaozhou, Shaoguan, and Qiongzhou. These were known mnemonically as “Guang Hui Zhao Chao Jia, Lei Lian Gao Shao Qiong”, and Guang-Hui-Zhao was used as a collective term for the various counties and cities under the jurisdiction of Guangzhou, Huizhou, and Zhaoqing prefectures.

In Singapore and Malaysia, Guang-Hui-Zhao represents the parts of Guangdong province where most of the Cantonese immigrants originally came from. Even though the Huizhou prefecture had a majority Hakka population, the Hakkas were naturally integrated into the Guangzhou and Zhaoqing community since they had gone to sea via Guangzhou.

The Cantonese are also known as Guangfu people, and the Cantonese language is also referred to as the Guangfu dialect. This is because, as the administrative centre of the Guangdong province, Guangzhou was deemed to be representative of the region. Guangfu is an abbreviation of “Guangzhou Fu” (Guangzhou prefecture).

Bound by kinship and geography

The first kinship-based organisation in Singapore was the Sing Chow Chiu Kwok Thong Cho Kah Koon, founded in 1819 by Chow Ah Chey (1782–1830), who was from Taishan and had arrived on the island with the Raffles expedition. Cho Kah Koon was located at the junction of Lavender Street and Kallang Road, and this downstream area of the Kallang River was where the Cantonese engaged in sawmilling, leatherworking, and masonry, and later ventured into the machinery industry.2

Chow Ah Chey and his fellow men from Taishan went on to establish Ning Yeung Wui Kuan in 1822 — the first Chinese clan association seen in Singapore as well as outside of China.3 Other region-based clan associations formed by Guang-Hui-Zhao people in the 19th century included Huizhou (Wui Chiu Fui Kun, 1822), Zhongshan (Chung Shan Association, 1837), Nanshun (Nam Sun Wui Kun, 1839), Gangzhou (now Xinhui, Kong Chow Wui Koon, 1840), Dong’an (Tung On Wui Kun, 1870), Zhaoqing (Siu Heng Wui Kun, 1878), Panyu (Poon Yue Association, 1879), and Sanshui (Sam Sui Wui Kun, 1886). There were also kinship-based clan associations such as Lau Kwan Cheong Chew Ku Seng Wui Kun (1873) and Kwong Wai Siew Li Si She Shut (1874).4

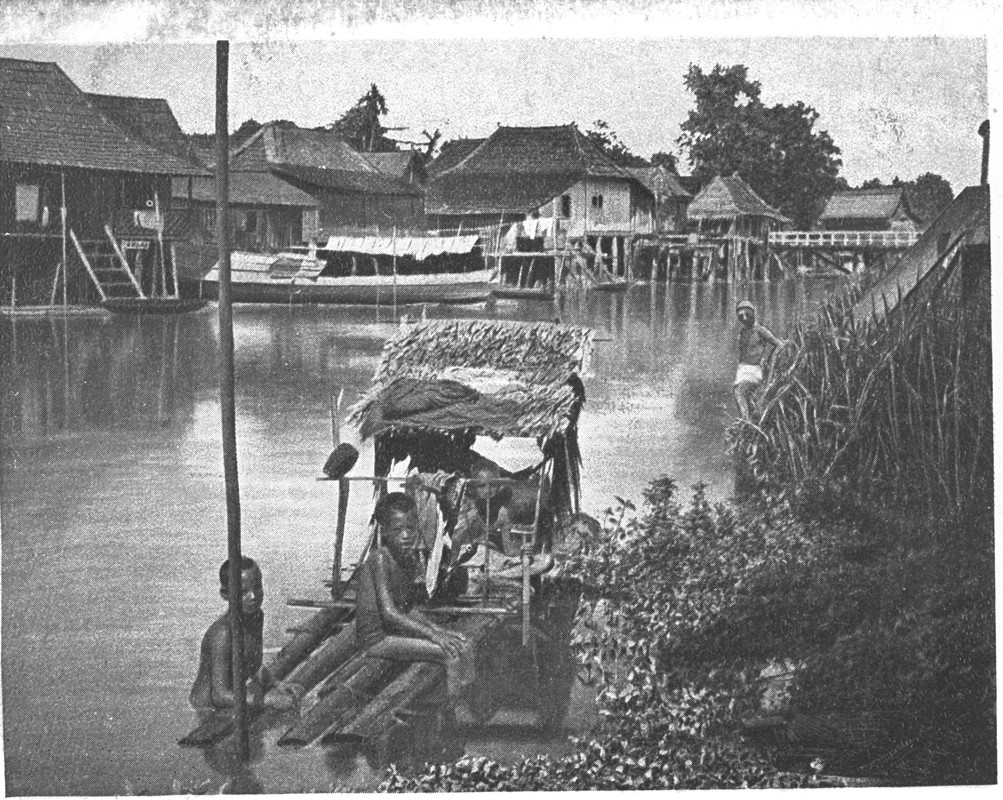

In Singapore, people from neighbouring regions in the Guangdong prefecture often started clan associations together. For example, Nam Sun Wui Kun included members from the counties of Nanhai and Shunde, and people from Nanhai and Shunde passing through Singapore on their way to South Africa for mining would stay at lodgings set up by the clan folks along Hongkong Street. Tung On Wui Kun was made up of people from the Dongguan and Bao’an (Shenzhen) counties, and its early members were mostly sailors. Chen Loong Wui Koon, founded in 1947, covered the counties of Zengcheng and Longmen.

Opera and lion dance

Clan associations established in the 19th century were characterised by their mission of supporting public welfare and improving the lives of those back in their hometowns. In the late Qing dynasty, Cantonese opera troupes from China sought opportunities abroad and the Liyuan Tang was set up in Singapore in 1857 (“Liyuan” is a term referring to opera troupes). It was later registered as Pat Wo Wui Kun in 1890, in compliance with requirements of the colonial government. The name “Pat Wo” is taken from the phrase ba tang he he, he zhong gong ji, which means a union of eight opera departments (roles) working in harmony. It symbolises the aspiration for concord among all professional actors in the troupe and the goal of bringing joy to the public.

The 20th century saw a diversification in the way clan associations were organised. For instance, Yi Yi Tang Lion Dance Troupe — which was established in 1920, and the first to perform lion dance at the Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng to honour ancestors — used lion dance as a means to unite fellow members, only setting up Hok San Association many years later in 1939.5 Shun Tak Community Guild was founded in 1948 to raise funds for flood victims in its hometown, and many of its members also belonged to Nam Sun Wui Kun.6These clan associations were concentrated in and around Chinatown in the early days, but some started to acquire property in Geylang as the city area underwent redevelopment.

Samsui women and Majie

Most of the Cantonese women who migrated south from China to seek a living in this region at the start of the 20th century originated from the counties of Sanshui (now Sanshui District) and Shunde (now Shunde District). They became members of Sam Sui Wui Kun, Nam Sun Hui Kun, and Shun Tak Community Guild, and formed a majority in these clan associations.

Those who came from Sanshui mainly worked at construction sites and were colloquially known as samsui women or hong toujin — literally “red headscarf”, a nod to their trademark red headgear. The ones who wore blue headgear instead would have been from the counties of Huaxian and Qingyuan. As for women from Shunde who worked as domestic servants in Singapore, most of them had sworn themselves to celibacy and were commonly called zishunü (self-combed women) or majie.7 In their later years, some would receive help from the clan associations to return to their hometowns, while the others would live out their days in a Gu Po Wu (spinsters’ house) or a temple known as a vegetarian hall.8

Today, the families of the early immigrants have long sunken roots in this land, and the role of clan associations has had to evolve. Since the 1990s, the Cantonese clan associations in Singapore have taken turns to host international conventions to foster connections among the Chinese diaspora around the world. Such cross-border reunions have become one of the main activities through which clan associations engage with the global community. The Cantonese clan associations of Singapore continue to preserve valuable artefacts as well as history and heritage — promoting Cantonese opera and cuisine, lion dance, festivals, and other distinctive cultural features.

The signatories on the land deed of the Ning Yeung Wui Kuan were Liang Yakuan and Dai Yahong, not Chow Ah Chey. The latter had already died in 1830 and could not have received the deed. Someone must have accepted it on his behalf when the colonial government issued it later on.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡广东人的会馆. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Lee Kok Leong, Dayanji, yueyangren [Breaking the Waves], 244–253. |

| 2 | Loo Say Chong and Ang Yik Han, Toutao zhibao, Wanshangang Fudeci lishi suyuan [A boon returned: The history of Mun San Fook Tuck Chee], 13. |

| 3 | Au Yue Pak, “Deng lu xinjiapo de cao yazhi” [Chow Ah Chey’s arrival in Singapore], Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng’s Yang, No. 18 (February 2009): 5. |

| 4 | Lee Kok Leong, Dayanji, yueyangren [Breaking the Waves], 89–98, 214. |

| 5 | Huo Bingquan, ed., Heshan Huiguan [Hok San Association] (Singapore: Singapore Hok San Association, 2015), 25. |

| 6 | Guanghuizhao Bishan ting qingzhu 128 zhounian teji [Commemorative issue of the 128th anniversary of Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng] (Singapore: Kwong Wai Siew Peck San Theng), 21, 25. |

| 7 | Lee Kok Leong, Guangdong Majie [Majie from Guangdong] (Singapore: Shun Tak Community Guild, 2015). |

| 8 | Show Ying Ruo, “Xinjiapo Yalong qu Xiantiandao zhaitang diaocha” [Survey on the Xiantiandao vegetarian halls in the Geylang area of Singapore], Fieldwork and Documents: South China Research Resource Station Newsletter, No. 87 (2017). |

Lee, Kok Leong. Dayanji, yueyangren [Breaking the Waves]. Singapore: Traveler Palm Creations, 2017. | |

Lee, Swee Har, Zhuisu guangfu wenhua, xing dao xin zhuan [Tracing Guangfu culture: a new perspective on Singapore]. Singapore: InfoMedia Publishing, 2022. | |

Loo, Say Chong and Ang, Yik Han, Toutao zhibao, Wanshangang Fudeci lishi suyuan [A boon returned: The history of Mun San Fook Tuck Chee]. Singapore: Selat Society, 2008. |