Stories behind the stones: Bukit Brown Cemetery

The rolling hills of Bukit Brown Cemetery are the final resting place of many of Singapore’s Chinese pioneers, ranging from the rich to the poor, and the illustrious to the obscure. They include not just prominent businessmen such as Chew Boon Lay (1852–1933) and Cheang Hong Lim (1841–1893), but also rickshaw pullers and ordinary people killed in World War II. The tombs, a blend of East and West, are a trove of material culture, featuring carvings of Chinese folklore, Sikh guards, winged angels and golden bells.

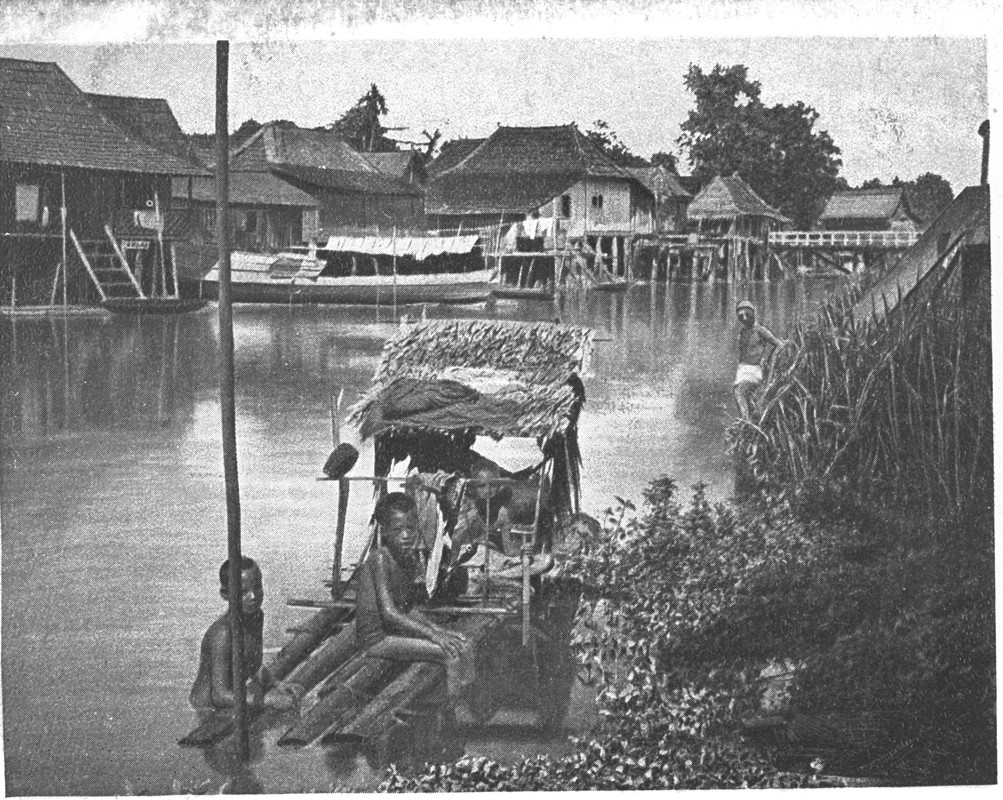

Bukit Brown (“Brown’s Hill”) is the first placename in Singapore made up of words from different languages — in this case, Malay and English. It first appeared on a map in 1898 and was named after British businessman George Henry Brown (unknown–1882)1, who came to Singapore in the 1840s, after spending time in Calcutta and Penang. Upon his arrival in Singapore, he bought a large plot of land to try his hand at planting nutmeg and coffee — which turned out to be failed ventures.

Brown, who would eventually leave Singapore and die in Penang, sold the land to Chettiar Mootapa Chitty (birth and death years unknown) and Chinese businessman Lim Chor Ghee (birth and death years unknown). In 1872, three businessmen from the Hokkien Ong clan acquired 211 acres (85.4ha) of the land from Chitty and Lim and initially earmarked the plot as a village for poorer members of the Ong clan. The land later became a burial ground called the Seh Ong Cemetery.

A common burial ground for the Chinese

At the turn of the 20th century, a few Straits-born Chinese came forward with an ambitious proposal for a common Chinese burial ground. Doctor and social reformer Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957) first raised the idea of a Chinese municipal cemetery in 1906, with Tan Kheam Hock (1862–1922) and See Tiong Wah (1886–1940), who were municipal commissioners, later lobbying the colonial government for Bukit Brown to be the location. The municipal government subsequently acquired part of Seh Ong Cemetery, totalling 98 acres (39.7ha) from the Hokkien Ong clan between 1918 and 1919, to be used for the new burial ground.

Bukit Brown Cemetery, which officially opened on 1 January 1922, was the first Chinese municipal cemetery in Singapore. It was administered by the British, and open to all Chinese — regardless of dialect group, kinship ties, or social status.

At first, the Chinese were reluctant to be buried close to those unrelated to them and in standardised lots that faced designated directions, which disregarded fengshui. Several months would pass before the first recorded burial took place at the municipal cemetery, and according to the burial registry, only 93 burials took place in its first year of operation. However, as social luminaries, such as See, booked plots for their families in the cemetery, the Chinese community eventually warmed to the idea of being buried there. By 1929, more than 40% of all officially registered Chinese burials were interred at Bukit Brown.

The municipal cemetery was officially closed for burials in 1973 as part of the government’s efforts to conserve land for development. The first burial recorded after the cemetery became a municipal cemetery was on 5 April 1922, while the last recorded burial was on 4 December 1972. Both of the deceased were women.

Estimating the number of graves at the Bukit Brown Cemetery is a daunting task. Due to limited knowledge of the actual terrain and burial patterns on the cemetery ground, figures may vary depending on the source. The Bukit Brown burial registry on the National Archives website recorded more than 89,000 interments from 1922 to 1972 when Bukit Brown became a Chinese municipal cemetery. However, researchers put the figure at more than 100,000 after taking into account burials that were not recorded in the burial registry, while the Ministry of Environment documented 67,400 graves in 1973, according to a public talk in 2014 by cartographer Mok Ly Yng, who has done extensive research related to the cemetery’s terrain. There are other older cemeteries in the vicinity of Bukit Brown Cemetery, including Lao Sua, Kopi Sua and Seh Ong Cemetery, so the number of graves would be much larger if those were also accounted for.

Tombs of trailblazers and war heroes

Home to a vast number of graves, Bukit Brown offers a precious glimpse into Singapore’s history in immigration, social, trade, and material culture.

Some of the earliest graves in the vicinity date back to the Qing dynasty’s Daoguang era (1820–1850). The oldest grave in Bukit Brown belonged to Fang Shan (unknown–1833), while the adjacent Lao Sua cemetery has an even earlier tomb dated 1826 belonging to Xie Guangze (unknown–1826) from Fujian, China. Both tombs had been relocated to Bukit Brown from the now-defunct Hokkien cemetery Heng San Teng.

Some inhabitants of Bukit Brown were trailblazers in their own right, such as Chew Boon Lay (1852–1933), who arrived in Southeast Asia penniless but later became the biscuit king of Singapore; Lee Choo Neo (1895–1947) who was the first female medical practitioner in Singapore and an aunt of founding prime minister Lee Kuan Yew (1923–2015); and Tay Koh Yat (1880–1957), a World War II hero who also owned a bus company that was once the largest in Singapore.

Other well-known pioneers whose tombs were relocated to Bukit Brown from elsewhere include Tan Kim Ching (1829–1892) — eldest son of Tan Tock Seng (1798–1850) and a friend of King Mongkut of Siam (1804–1868) — as well as “Opium King” Cheang Hong Lim (1841–1893).

Bukit Brown also has its fair share of stories of ordinary people. Not far from Tay’s tomb is the resting place of 19-year-old Soh Koon Eng (unknown–1942)2, who used her body to shield her family from a Japanese bomb during World War II. Then there is Low Nong Nong (unknown–1938), a rickshaw puller who died during a clash between the police and rickshaw pullers on strike. His tomb, located in the pauper’s section, was erected by fellow rickshaw pullers. Principal Lim Chek Yong (unknown–1948), a lifelong bachelor who had devoted his life to education, was buried by the Chinese Industrial and Commercial Continuation School (now known as Gongshang Primary School) which he ran.

Treasure trove of material culture

The largest tomb in the cemetery belongs to Ong Sam Leong (1857–1918), a wealthy plantation owner and contractor of phosphate mines on Christmas Island. Ong’s tomb, complete with a moat, covers 600 sq m, the size of nearly 10 three-room Housing and Development Board (HDB) flats. It contains some of the most eye-catching material culture in Bukit Brown — stone lions in their eastern and western forms, the Golden Boy and the Jade Girl, carvings of classical Chinese stories, and Sikh guards, to name a few. Chinese lions, with the male usually resting his paw on a ball and the female tending to a cub, are believed to bless the family. The Golden Boy and the Jade Girl, on the other hand, are tasked with guiding the deceased in the underworld.

Common stories etched on more elaborate tombs at Bukit Brown include scenes from Madam White Snake, Romance of the Three Kingdoms, and the Eight Immortals. Ong’s tomb, which has the luxury of space, features intricate carvings of The Twenty-four Filial Exemplars.

Some tombs in Bukit Brown contain features that are unique to Southeast Asia and not found on traditional tombs in China. Banker Chia Hood Theam’s (1863–1938) tomb, for example, contains the Chinese name of the deceased, but other information about him is in English. Other western features include cherubic angels guarding the tomb of trader Teo Chin Chay (unknown–1935), and liberty bells on the tomb of philanthropist Tan Boo Liat (1874/5–1934)3, great-grandson of Tan Tock Seng.

The tombs are also etched with different calendars that reflect the times in which they were erected. Most use the Republic of China or Minguo calendar, while others follow the Gregorian calendar, the reigning eras of Ming and Qing emperors, or the Japanese Koki or Showa calendars that are typical of World War II tombs.

Another noteworthy tomb belongs to the sinseh (traditional Chinese physician) Chew Geok Leong (unknown–1940)4, which has two painted Sikh guards — a sign of how the privileged wanted their trusted bodyguards to watch over them even after death. Other tombs have vibrant decorative tiles which were widely used in houses during the British colonial era.

Making way for the living

In 2011, the Singapore government announced plans to construct a multi-lane road that would bisect Bukit Brown Cemetery, which itself spans an area bigger than the Singapore Botanic Gardens. More than 4,000 tombs were exhumed to make way for the road — now known as Lornie Highway, which was completed in 2019. More exhumations are likely to come as the Bukit Brown area has long been earmarked for residential development, as shown in the government’s Concept 1991 plan.5

In a race with time after the 2011 announcement, heritage and nature enthusiasts spoke up on the need to preserve the site, with volunteers stepping up efforts in conducting guided tours, chronicling personalities buried there, and recording the flora and fauna teeming the luxuriant grounds. The movement gained traction with a group called all things Bukit Brown (atBB) leading a series of efforts that resulted in the cemetery being included on the list of the World Monuments Watch, a sold-out book World War II@Bukit Brown, and the launch of the Bukit Brown Spirit Film Festival. In August 2024, atBB worked with the Singapore Heritage Society to erect the Sounds of the Earth memorial using 80 unclaimed artefacts from tombs exhumed to make way for Lornie Highway.

Known to heritage enthusiasts as an open-air museum, Bukit Brown is packed with personalities and tombs that reflect Singapore’s multiculturalism. There are still more stories waiting to be unearthed, stories that will help future generations better understand the past.

| 1 | George Henry Brown’s grave in Penang stated that he died on 5 October 1882 at age 63. |

| 2 | Her death certificate stated the date of death as 27 January 1942. It did not, however, mention the date of birth, which may be 1922 or 1923. |

| 3 | Various sources put his birth year as 1874 or 1875. |

| 4 | While other death years have been stated on different websites, 1940 is the date on the tomb. |

| 5 | This was not the first time that graves in the cemetery had been exhumed to make way for development. In 1965, more than 200 tombs were exhumed to make way for the re-alignment of Lornie Road; in 1993, some 600 graves were exhumed to allow for the expansion of the Pan Island Expressway (PIE). See “Bukit Brown Municipal Cemetery”, Singapore Infopedia, National Library Board. |

1911 Revolution: Singapore Pioneers in Bukit Brown. Singapore: Sun Yat Sen Nanyang Memorial Hall, 2016. | |

Bukit Brown Wayfinder: A Self-Guided Walking Tour. Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society, 2017. | |

Huang, Jianli. Resurgent Spirits of Civil Society Activism: Rediscovering the Bukit Brown Cemetery in Singapore. Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society87:2 (2014), 21–45. | |

Hui, Yew-Foong, Feng, Chen-Chieh and Neo, “Grave Matters: Spatial-temporal Analyses of Bukit Brown and Seh Ong Cemeteries.” National Heritage Board’s Roots, 31 March 2024. | |

Leow, Claire and Lim, Catherine. World War II @ Bukit Brown. Singapore: Ethos Books and Singapore Heritage Society, 2016. | |

Lim, Chee Kiong Walter. Chenfeng yishi, cong wuji bulang zhui su xinhua liangbainian [Forgotten anecdotes: tracing the 200 year history of Singapore Chinese through Bukit Brown cemetery]. Singapore: kafeishan wenshi yanjiu, 2020. | |

National Archives of Singapore. Bukit Brown Burial Registers. | |

Ng, Keng Gene and Kevin Lim. “Markers of the Past: Unclaimed Tombstones at Bukit Brown.” The Straits Times, 28 August 2024. | |

Tan, Audrey. “Singapore’s History to Come Alive in New Book Focusing on Bukit Brown.” The Straits Times, 5 April 2016. | |

Teo, Jennifer. Do-It-Yourself Bukit Brown Tour — A Pocket Guide By The People. Singapore: Selitar Press, 2022. | |

World Monuments Fund. 2014 World Monuments Watch |