Traditional trades of the Cantonese community in Singapore

From the 19th to the mid-20th century, the diversity of Singapore’s Chinese community was reflected in a system or bang, based on dialect groups. One feature that best demonstrates this structure was the trade specialisation among the different dialect groups. In the business sector, certain industries were monopolised by specific dialect groups. The Cantonese, the third-largest dialect group in Singapore in terms of population, were mainly involved in local industries, particularly those related to personal services and crafts.

In Singapore, the Cantonese are not narrowly defined as the Cantonese-speaking community or immigrants from Guangdong. Rather, they are understood to be immigrants from Guangzhou, Huizhou, and Zhaoqing prefectures, collectively known as the Kwong Wai Siew (Kwong Wai Shiu) community. Hakka immigrants from Huizhou formed the Kwong Wai Shiu community with Cantonese-speaking immigrants from Guangzhou and Zhaoqing, as most of the immigrants from Huizhou left for Singapore via Guangzhou, like those from Guangzhou and Zhaoqing. Moreover, Huizhou is geographically close to Guangzhou, and its residents were mostly proficient in Cantonese. All these factors had brought together the Hakkas in Huizhou and the Cantonese in Guangzhou and Zhaoqing.

Economic pillars of the Cantonese community

Compared with the Hokkien and Teochew communities which invested in gambier plantations, established banks, and actively built business networks, the Cantonese were in a relatively weaker economic position. They were mainly involved in seven industries, including grocery retail, gold and silver pawnbroking, construction and transport, garment manufacturing, daily necessities retail, food and beverage (F&B) and tourism, and traditional Chinese medicine. With the exception of relatively key industries such as grocery retail and construction and transport, the other trades were more related to localised personal services and crafts.

The grocery retail industry was the Cantonese community’s strongest economic trade. They brought in all kinds of products from Guangdong to sell in Singapore, including cigarettes, firewood, rice, oil, salt, sauces, vinegar, and tea. As these goods came from Guangdong, they were known as guanghuo (Guangdong goods). Merchants from Xinhui and Heshan played a key role in this industry. While Heshan businessmen set up many provision shops in Hong Kong Street near the Singapore River, those from Xinhui were even more influential. In the early 19th century, the Choo and Loh families came to Singapore and established businesses in Market Street, where the Hokkiens made their fortunes. Loh Kee Seng, Choo Kong Lan, Choo U Lan, Kwong Hang, Loh Chee Seng, Tong Tak, and Choo Foo Lan, collectively referred to as the “Seven Shops of Market Street”, monopolised the grocery retail market at that time. The seven merchants also served as the first chairmen of the Thong Chai Medical Institution, an organisation that transcended dialect group identity, testifying to the influence of Xinhui merchants in Singapore’s Chinese community.1

Although the influence of the seven merchants waned considerably in the early 20th century, their kin and clansmen continued the Xinhui merchants’ leadership in the industry by establishing businesses collectively known as the “Little Seven Shops”. In 1908, they jointly set up the Singapore Dried Goods Guild with other Cantonese grocers. Later in 1939, a group of Cantonese grocers formed another trade association — the Kwong Foh Hong.

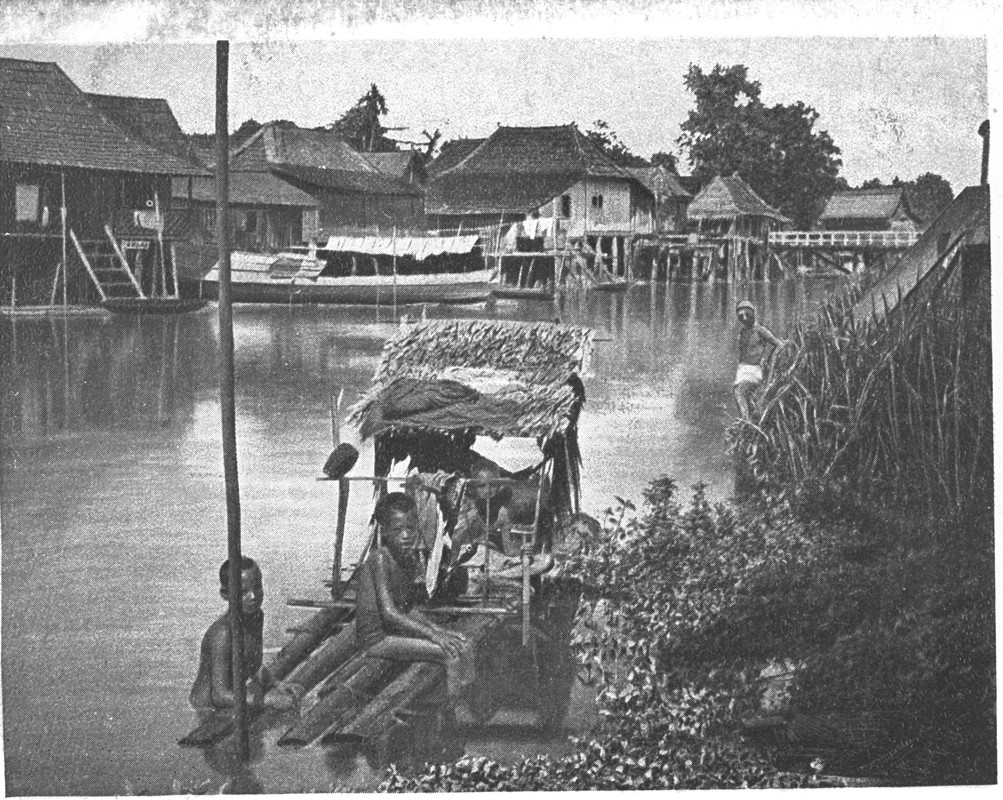

The construction and transport industry was regarded as another economic pillar of the Cantonese. As early as the 19th century, the Kallang River areas became another main enclave of the Cantonese community besides Chinatown. Thanks to their location, the areas along the Kallang River saw the development of waterway transport, shipyards, brick kilns, and other related industries. Boey Nam Lock (birth year unknown – 1914), a merchant from Taishan, started his career in the construction industry and set up a tannery in Kallang. Today, there is a Nam Lock Street in Kallang to commemorate Boey’s contributions. Cantonese workers in the construction industry are also credited with starting the two earliest trade associations in Singapore — the Pak Seng Hong, established in 1867, and the Lo Pak Hong, founded in 1890. This reflected the influence of the Cantonese in the construction industry during the 19th century.

In the early 20th century, women from Guangdong who came to Singapore in search of a livelihood also joined the construction industry. Those who came from Sanshui and Shunde mostly worked at construction sites, and were colloquially known as samsui women or hong toujin (red headscarf), a nod to their trademark red headgear. Some women from the county of Huaxian also worked in the construction industry, and were known as lan toujin because they wore blue headgear. Those from Dongguan, on the other hand, worked as cleaners in dockyards, and were known as hei toujin because of their black headscarves. The inclusion of women further consolidated the position of the Cantonese in Singapore’s construction and transportation industry.

Leaving their mark in diverse trades

In addition to the two major trades mentioned above, the Cantonese were also involved in a variety of personal services and the crafts. From the 19th century to the mid-20th century, the Cantonese established several trade associations that reflected their involvement in a variety of trades.

The Gold & Silver Workers Union (Singapore Branch) established in 1908, and the Kheng See Hong founded in 1929, were associations started by the Cantonese which were related to the gold and silver pawnbroking industry. In the garment manufacturing industry, the Cantonese founded the Hean Yuen Merchant Tailors Association as early as 1880, and subsequently established The Singapore Chinese Textiles & Sundries Importers’ Union, the Chinese Tailors Union, How Fook Tong, and the Chinese Laundry Owners Association. These trade associations reflected the active involvement of the Cantonese in the garment manufacturing industry.

The Cantonese also set up trade associations related to the daily necessities, F&B, and tourism sectors. To distinguish these associations from similar organisations established by other dialect groups, the names of these associations bore the word “Cantonese”, such as the Cantonese Butcher Association, the Cantonese Grocers’ Association, the Cantonese Cooked Food Sellers’ Association, and the Cantonese Rattan Workmen’s Benevolent Fund. In the printing industry, the Cantonese formed the Chinese Printing Workers’ Union and the Master Printers’ Association. In the food industry, the Ku So Shan Keng Thong, founded in 1876, is the oldest Cantonese F&B association.

The numerous trade associations mentioned above not only reflect the diversity of trades that the Cantonese community was involved in, but also depict the many facets of their lives in Singapore.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡广东人的传统行业. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Au Yue Pak, “Bainian qian chengba zhongjie de qijiatou: hongyan, zahuo, jiangyuan dawang” [Seven shops of Market Street a century ago: Kings of tobacco, groceries and soy sauce], in Kong Chow Wui Koon 150th Anniversary Celebration Souvenir Magazine, edited by Kong Chow Wui Koon (Singapore: Kong Chow Wui Koon, 1990), 42–52. |

| 2 | Yang Yan, “A brief history of Chinese medicine in Singapore,” in Routledge Handbook of Chinese Medicine, edited by Vivienne Lo, Michael Stanley-Baker and Dolly Yang (London: Routledge, 2022), 528–531. |

Chan, Hong Yin. “A Preliminary Study of the Social History of the Cantonese Chinese Community in Singapore.” Translocal Chinese: East Asian Perspectives 16, no. 2 (2022): 151–180. | |

Xingzhou guanghuo hang di shisi zhounian jinian tekan [The 14th anniversary commemorative booklet of Kwong Foh Hong]. Singapore: Kwong Foh Hong, 1953. | |

Xinjiapo gusu shenjing tang chajiulou hang chengli yibai zhounian jinian tekan [The 100th anniversary commemorative booklet of Singapore Ku So Shan Keng Thong Restaurateurs Association]. Singapore: Ku So Shan Keng Thong Restaurateurs Association, 1976. |