Traditional trades of the Teochews in Singapore

Influenced by clan kinship and geographical ties, early Chinese immigrants in Singapore often hired fellow clansmen to help run their businesses. Having learnt the ropes of the trades and accumulated enough capital, these workers would often set up their own businesses in the same industries. Gradually, some businesses became the traditional trades of specific dialect groups. Over time, as the business environment changed, other dialect groups also ventured into these industries, while some traditional trades were gradually phased out by society.

Gambier and pepper cultivation

Before the founding of modern Singapore in 1819, there were already Teochew settlers on the island engaging in gambier and pepper cultivation, which were the earliest traditional trades of the Teochews. By 1848, gambier and pepper plantations accounted for 76% of the island’s total arable land, with over 90% of the operators being Teochew. Some of them became wealthy, such as Seah Eu Chin (1805–1883), Chan Ah Lak (1813–1873), and Su Tianfu (unknown–1913).

From the late 19th century to the early 20th century, changing market demands prompted Teochew businessmen to move into the emerging pineapple and rubber planting industries. For instance, canned pineapples produced by Seah Liang Seah (1850–1925) were popular in the region, Europe and the United States, while Lim Nee Soon (1879–1936) was the largest supplier of pineapples in Nanyang, earning him the nickname “Pineapple King”. Lim also pioneered rubber plantations spanning more than 20,000 acres in Singapore and Johor. During the same period, Teochews such as Teo Eng Hock (1872–1959), Leow Chia Heng (1874–1931), Seah Peck Seah (1859–1939) and Li Xingyan (1878–unknown) ran thriving rubber processing plants. These plantations and factories hired tens of thousands of Teochew workers, while their upstream and downstream supply chains were also dominated by Teochew businessmen.

Fishing and farming

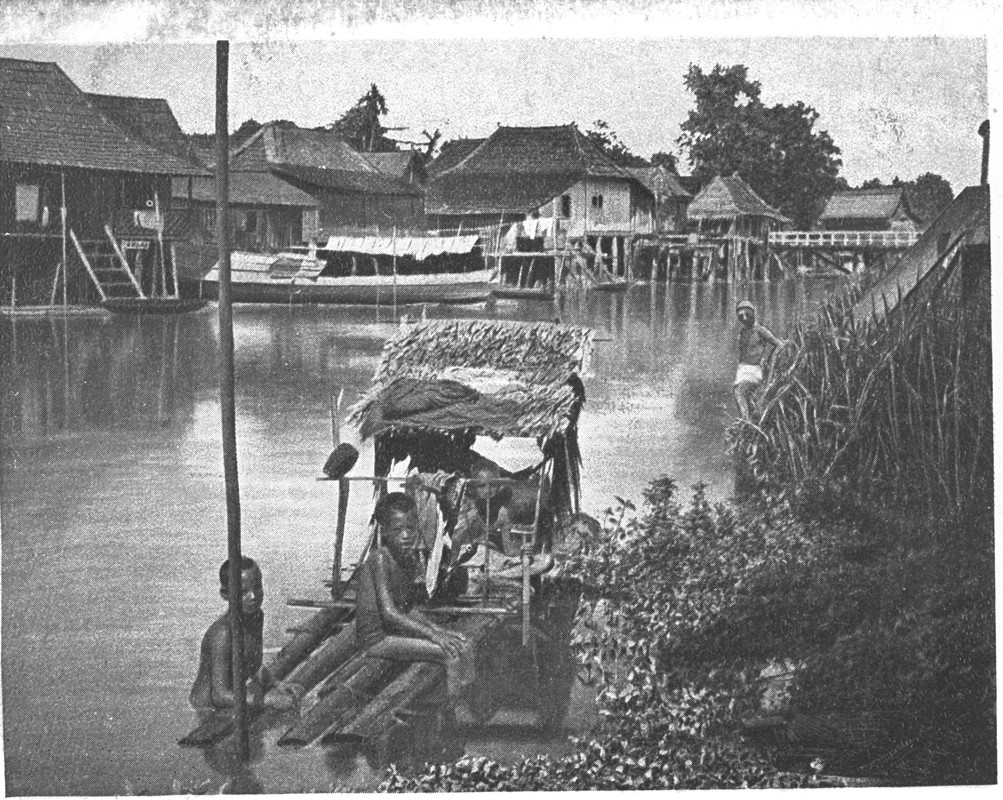

Vegetable growing, fishing and pig farming were also traditional trades of Teochews in early Singapore. Many Teochews from Huilai grew vegetables in the Mandai area, also known as “Little Huilai”, and most of the vegetable wholesalers were Teochews. The early vegetable wholesale markets were located in Carpenter Street. Before World War II, Teochew-run kelongs accounted for nearly half of the kelongs owned by the Chinese.1 After the war, there were still close to 100 Teochew-owned kelongs in the sea around Changi, Bedok, Pulau Tekong, Pulau Ubin and Pasir Panjang. The wholesale fish markets in Koh Sek Lim Road and Hougang Kangkar were the stronghold of the Teochew fishing trade, while pig farming was concentrated in the Punggol suburb where many Teochews lived.

‘98% trades’ and the rice trade

After Singapore was established as a free port in 1819, its trade grew rapidly, with Teochew immigrants playing an active role in commercial activities. Some wealthy traders engaged in entrepot trade, charging a 2% commission on the sale of goods for their intermediary role in business dealings. They were therefore also known as jiubahang (“98% trades”). This traditional industry mainly dealt in the trade of various local products, with traders importing goods such as seafood, bird’s nest, dried goods, rice and palm oil from Hong Kong, Shantou, and Southeast Asia. Some of these goods were distributed locally, while the rest were exported to Australia, Japan and the United States as well as to Europe and the Middle East. In addition, they sold Nanyang products and European industrial goods to mainland China via Hong Kong and Shantou. Through this business model, Teochew merchants established a unique trading network centred on Nanyang products and connecting the markets of the East and West.

In the early days, Teochew merchants dominated the rice trade in Singapore. Key figures in the industry before World War II included Chua Chu Yong (1847–unknown), Nah Kim Seng (1859–1919), Tan Sam Er (1891–1952) and Tan Keng Khor (1895–1945), some of whom operated rice mills in Bangkok. By the mid-20th century, Teochew merchants accounted for over 70% of the local wholesale rice market. The reputable Tan Guan Lee, Chop Wee Heng, Yuan Long Sheng Ji and See Hoy Chan were companies that monopolised the industry.

Textile, porcelain, and other traditional trades

The wholesale textile industry was also traditionally associated with the Teochews. In the early days, textile shops of all sizes run by Teochews were concentrated at Circular Road, colloquially known as zab boih goin ao (literally, “behind the 18 units”). After 1980, some businesses relocated to the Textile Centre in Jalan Sultan Road, importing mainly fabric, silks and satins from China, Europe and Japan. In addition to supplying local retailers, they also sold their products to Southeast Asian countries.

Teochew merchants were also involved in porcelain trading, with their shops clustered around Rochor Road and Beach Road. They primarily imported their wares from China, Japan and a few European countries, before selling them on to other parts of Nanyang. These merchants were also involved in wholesale and retail businesses in Singapore, establishing this trade as a traditional Teochew industry.

After Huang Jiying (birth and death years unknown) set up the Tee Seng remittance house in 1835, the Teochews began to venture into the remittance trade. By the 20th century, Teochew-owned remittance houses accounted for 70% of the local market, forming a trade network with distinct clan and ethnic ties. For example, the largest remittance house with the widest network, Chye Hua Seng Wee Kee, had branch offices and subsidiaries whose members and clientele from all over the world shared the same ancestral hometowns and clan roots.

Teochew merchants also gained a foothold in the lighterage industry, dominating this traditional trade alongside Hokkien merchants. The barge trade slowly declined after the Singapore River was transformed into a tourist attraction.

On the southern bank of the Singapore River was a Teochew settlement colloquially known as cha choong tow, a reference to a small jetty nearby where barges unloaded charcoal and fuelwood from Indonesia. The 1950s to 1960s marked the peak of the charcoal and fuelwood industry, with Teochew merchants accounting for more than 70% of the wholesale and retail markets. In order to meet demand, the small dock was relocated to larger ones in Tanjong Rhu and Serangoon River.

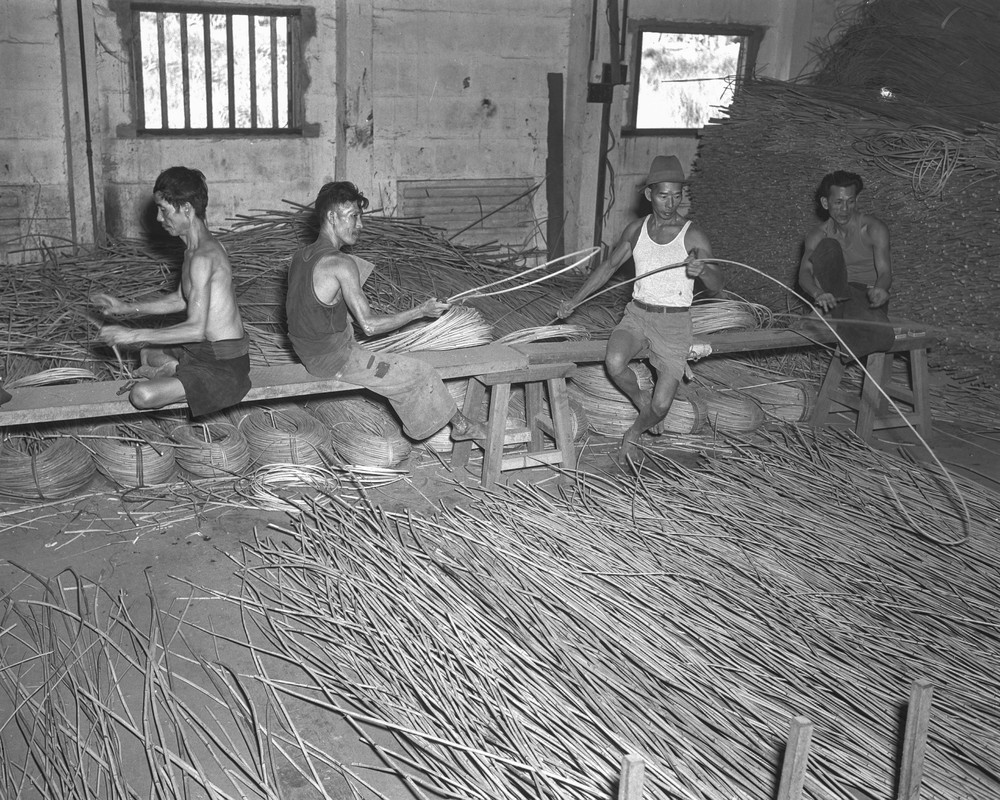

Among the traditional trades of the Teochews, the more unusual ones included bamboo and rattan weaving, as well as poultry hatching, which are no longer seen today.

In order to strengthen ties, secure better welfare for their fellow traders and safeguard shared economic interests, Teochew merchants in traditional trades actively established associations based on trade ties. These trade associations were established in the early 20th century, and some of the more influential ones include the Teochew Piece Goods Traders Guild (founded in 1908 and later renamed the Singapore Piece Goods Traders Guild), the Singapore Teochew Exchange Association (founded in 1929), the Singapore Retail Fish-sellers Guild (founded in 1940), the Singapore Cheohern Kimkuay Hiangswa Union (founded in 1945) and the Chinaware Merchants Association (founded in 1951). As the industries declined, these associations gradually dissolved at the end of the 20th century, becoming part of the historical memory of the Teochew community.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡潮州人的传统行业. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | The kelong is a traditional fishing method used by fishermen in Singapore and Malaysia. It consists of a platform built on wooden stilts with fishing nets laid underneath. The kelong serves as both living quarters for the fishermen and a tool for catching fish. |

Cheng, Lim-Keat. Social Change and the Chinese in Singapore: A Socio-economic Geography with Special Reference to Bang S Singapore: Singapore University Press, 1985. | |

Choi, Kwai Keong. “Xinjiapo chaozhouren dui jingji fazhan de gongxian” [The Contributions of the Teochew people to the economic development of Singapore]. In Xinjiapo chaozhou wenhuazhan tekan [Commemorative issue of the exhibition on the heritage of the Teochew community in Singapore], edited by Ang Hoon Seng. Singapore: Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan, 2002. | |

Goh, Choon Kang. “Xinjiapo taociye, jiu cheng yezhe shi chaozhou fengxiren” [Singapore’s ceramics industry: 90% of practitioners are from Fengxi, Chaozhou]. Lianhe Zaobao, 27 February 2025. | |

Phua, Chay Long. Malaiya chaoqiao tongjian [The Teochews in Malaya]. Singapore: South Island Press, 1950. | |

Siah, U-Chin (Seah Eu Chin). “The Chinese in Singapore, General Sketch of the Numbers, Tribes and Avocations of the Chinese in Singapore.” Journal of Indian Archipelago and East Asia II (1848): 283–290. |