Pioneer artist: Yeh Chi Wei

Born in Fuzhou, China, Yeh Chi Wei (1913–1981) spent his childhood in Sibu, Sarawak, where his family made a living by clearing forests to grow rubber trees and various crops. In 1925, Yeh returned to Fuzhou to further his studies. Due to his strong interest in art, Yeh eventually enrolled to study Western painting at Xinhua Academy of Fine Arts in Shanghai, despite his father’s objections. After graduating in 1936, Yeh left for Singapore at the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War. After getting married and starting a family, Yeh worked as an art teacher in various schools in Sibu, Malaya and Singapore, and eventually settled down with his family in Singapore.

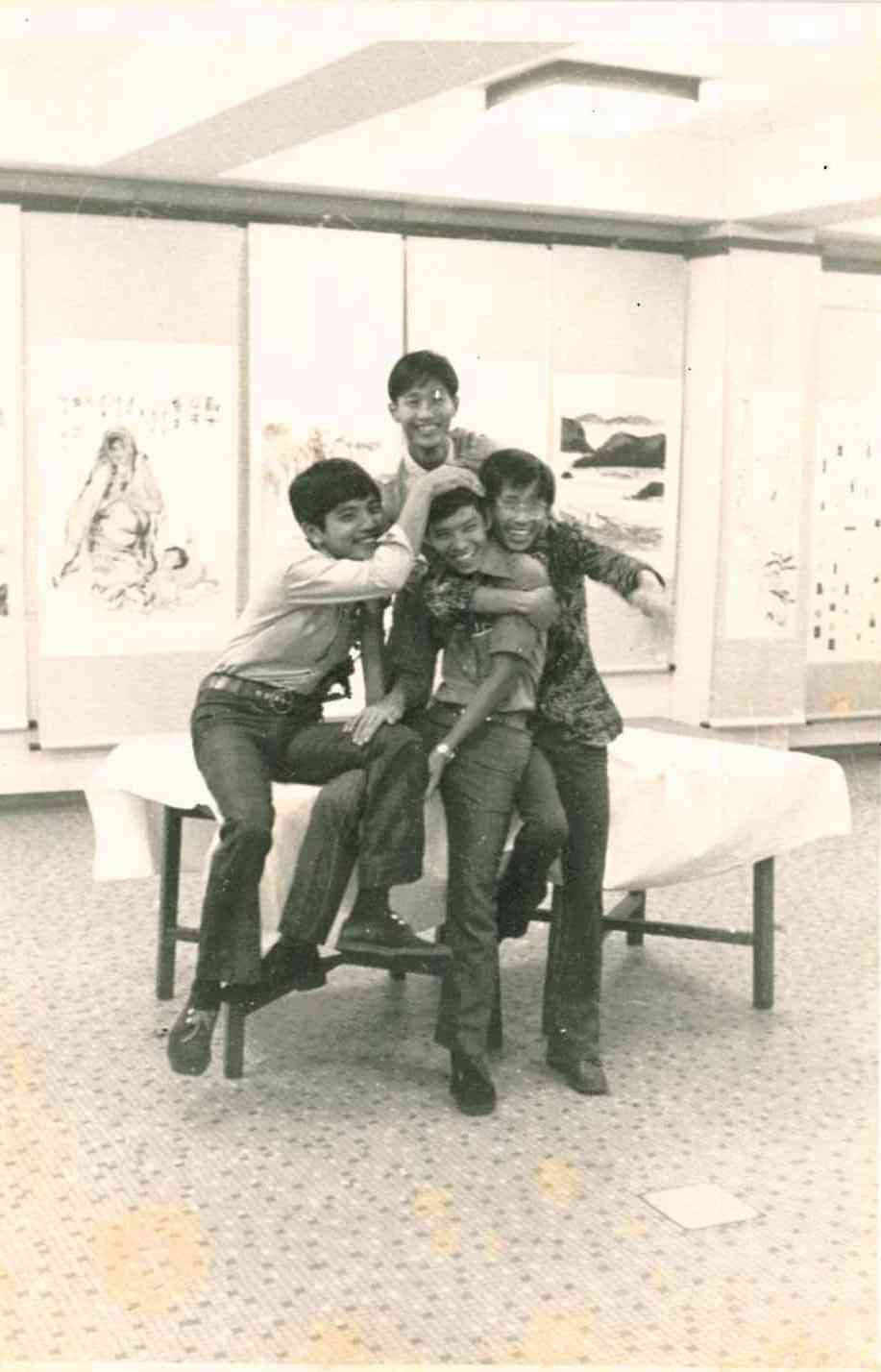

Yeh was a significant figure in Singapore’s 20th century modern art scene. First, he was an important art educator who formed part of the early cohort of professionally-trained artists who taught art to many young students in Singapore and Malaya from the early to mid-20th-century. Yeh’s impact was felt especially during his tenure at Chung Cheng High School in Singapore in the 1950s and 1960s. His former students recalled that he was a stern teacher with high standards. To encourage talented students who were keen to further their interest in art, Yeh helped set up the Chung Cheng High School Art Society in 1953, which organised regular art competitions and annual art exhibitions.

Second, Yeh was acknowledged as an influential leader of an informal collective of local artists known as the Ten Men Group. In the 1960s, this group made frequent trips to Southeast Asian countries and organised group exhibitions after their trips. Many of them were drawn to the local cultures of the countries they visited, which later became subjects of their paintings. At the time, it was unprecedented in Malaya for a large group of artists to organise themselves for overseas trips and then hold a thematic exhibition after each trip. It was even more remarkable that they did so over a sustained period, organising six trips and five exhibitions in less than a decade.1 The scale and sustained regularity of these trips and exhibitions was noteworthy, considering that travel was still a luxury in those days for most people, and considerable resources were needed to organise art exhibitions. Through his leadership of the Ten Men Group, Yeh went on to establish the Southeast Asian Art Association in 1970 (which, in itself, was also pioneering for its regionalist agenda) and was its founding president from its inception to 1977. This achievement placed Yeh among a select group of artists who had helped to found major art societies in Singapore. These included Liu Kang (Singapore Art Society in 1949) and Chen Chong Swee (Singapore Watercolour Society in 1969).

Third, Yeh was part of a special generation of China-born artists who shared a common historical background. Familiar with both Chinese and Western art, many artists of the period sought to integrate Western and Chinese art traditions in their practice. For those who later left China around the mid-20th century and found a safe haven in Singapore, they continued to pursue their artistic interests and eventually spearheaded modern art developments in their new home. Initially preferring to paint in a naturalistic mode due to his academic training, Yeh’s style changed in the 1960s. The Ten Men Group trips exposed him to different cultures and provided much stimulus in terms of subject matter, techniques and approaches. The trips also fostered his close friendships with like-minded local artists with whom he spent many hours painting together and discussing art. Yeh also started reading more about modern art developments, which revised his initial distaste for abstract art. Within this creative ferment, Yeh developed a distinctive body of semi-abstract oil paintings which incorporated his deep knowledge of Chinese art, and keen sensibilities to Southeast Asian cultures.

Southeast Asian influence

Yeh’s strong affinity for the region was reflected in his many paintings of Southeast Asian themes, particularly the indigenous communities of Borneo.1This was unsurprising as he had spent his early childhood in Sarawak, living close to nature. Later, as an adult in modern Singapore, he saw benefits in leaving behind the urban pressures of city life to seek the regenerative qualities of nature during the Ten Men trips. Hence, rather than being seen as backward or uncivilised, the simple ways of life of the Dayaks and Ibans and their closeness to nature were qualities that very much resonated with him. Yeh was also drawn to Southeast Asian material culture. Indigenous textiles and wooden carvings purchased by Yeh during his trips informed how he eventually stylised the figures in his paintings. Patterns on local textiles or carvings were also incorporated as motifs within his artworks. For instance, after his 1962 Indonesian trip, Yeh was inspired by Javanese batik, and began to “cover the entire canvas with flat colours” and “lay out decorative-looking images by means of simple colour tones and pattern-like lines.”3 This is reflected in works like Boats in Bali with their use of white negative outlines and flat colours, usually associated with traditional Indonesian textiles such as batik and ikat.4 These works are also distinguished by their long narrow compositions, which could have been inspired by the format of traditional textiles, or the artist’s familiarity with the hanging and handscroll tradition of Chinese painting.5

Incorporating ink rubbings

After Yeh’s trip to Thailand and Cambodia in 1963, his works changed again. To convey the solemnity of the ancient stone monuments he encountered, Yeh turned to his long-standing interest in Chinese calligraphy, in particular ink rubbings. In China, rubbings have traditionally been used to reproduce inscriptions or images carved onto hard substances like bone, bronze or stone. To make rubbings, a sheet of moistened paper is laid across the inscribed surface and pressed into all recessed areas with a brush. When the paper has nearly dried, its surface is pounded with an inked pad. This produces white characters or images on a black background because black ink does not touch parts of the paper that were earlier pressed into the carved inscription. Multiple copies may be made with this method. As rubbings were commonly used by calligraphers to study different ancient styles, Yeh had collected rubbings of oracle bone scripts, Western Zhou period bronze inscriptions and Han dynasty stelae carvings. These rubbings appealed to him for various reasons. Firstly, he was impressed by the sense of strength and weight of the inscriptions. Originally carved or cast on hard substances like stone or metal, these inscriptions did not have the lightness or fluidity of brush-written characters. Moreover, rubbings, being direct impressions of ancient inscriptions, were often seen as a tangible and authentic link to the past. Lastly, archaic writing on oracle bones and bronze vessels, were created mainly for ritual purposes, and hence, laden with historical, if not spiritual, associations. Therefore, Yeh might have felt that such qualities of gravity, antiquity, authenticity and ritualism were ideally suited to capture the majesty of the ancient monuments and rustic charms of Southeast Asia. On that basis, Yeh incorporated certain visual aspects of ink rubbings into his artworks. Black became a predominant colour in many of his oil paintings. His painted forms were often finished with softly blurred edges or framed within irregular outlines. These recalled the ravages of time seen on ink rubbings of ancient inscriptions. This is because such inscribed characters tended to lose their sharp edges due to damage or erosion over the centuries, and these imperfections were replicated whenever rubbings were made of such inscriptions.

In some works, Yeh even included archaic-style inscriptions (using a mixture of oracle bone and seal scripts) rendered in white against a dark background, akin to characters found in ink rubbings. The use of archaic scripts imparted a jinshi (meaning “metal and stone” refers to inscriptions on metal such as bronze vessels, and stone such as stelae metal and stone) flavour to his paintings. This was a style preferred by many early 20th century calligraphers and painters such as See Hiang To (1906–1990), Tsue Ta Tee (1904–1975), Reverend Song Nian (1911–1997), Chang Shou She (1898–1969) and Chan Tan-Nung (1903–1975). They admired the sense of strength and forcefulness found in inscriptions on ancient bronzes and stone stelae, and sought to convey a similarly rough-hewn aesthetic in their own practice.6 The jinshi taste was likely also the reason why Yeh preferred to use a palette knife. Unlike a brush used for smoothing out brushstrokes and executing fine details, a palette knife created angular strokes and left behind streaks of paint of varying thicknesses which could better convey the rustic simplicity sought by Yeh.

Despite his impact as an arts educator and leader, and the acclaim accorded to his works in the 1960s and early 1970s, Yeh faded out of the art scene in the late 1970s to live in Malaysia, and died in 1981 in relative obscurity. In recent years, his artistic achievements have started to regain attention, notably with a survey exhibition organised by the National Art Gallery Singapore in 2010.

| 1 | Interview with Yeh Toh Woi, 4 December 2009; Talk by Choo Keng Kwang at a forum held at Singapore Art Museum, 24 September 2005, in conjunction with the exhibition A Heroic Decade. By 1965, Ma Ge already regarded the group as “the longest exhibiting group of artists to date”. See Ma Ge, “Foreword,” Shiren huaji [Ten Men Art Exhibition—Tour of Sarawak] (Singapore, 1965), unpaginated. |

| 2 | Such works conveyed a romanticised view of Southeast Asian realities, as Yeh clearly preferred to depict the traditional and rural, rather than the modern and urban. For instance, while many of the longhouse inhabitants he met in Sarawak and Sabah wore a combination of modern and traditional clothes, he invariably portrayed them wearing exclusively traditional dress. |

| 3 | Yeh Chi Wei, “Artist’s Preface,” Ye Zhiwei huaji [Yeh Chi Wei Catalogue] (Singapore, 1969), unpaginated. |

| 4 | Ikat refers to a method of creating patterns on fabric by tie-dyeing the yarn before weaving. Batik refers to a method of creating dyed patterns on fabric, whereby portions of the fabric not intended to be dyed are covered with removable wax. |

| 5 | Most traditional Indonesian textiles are hand-woven on backstrap looms. The loom holds the lengthwise threads, called warps, under tension, while the weaver passes a crosswise thread, called a weft, between them. As such, the width of each cloth is limited by the width of the looms. |

| 6 | Starting from the late 18th century, large quantities of archaic oracle bones, bronzes and stelae were excavated in China, prompting interest in the study of inscriptions on such artefacts. Artists particularly admired the sense of strength and forcefulness of such inscriptions, and over time, preferred their “so-called rustic charms” over the “perfected elegance” of traditional calligraphic styles. (Shan Guolin, “The Cultural Significance of the Shanghai School,” Chinese Paintings from the Shanghai Museum 1851–1911 (Edinburgh: NMS Publishing, 2000), 200.) Artists like Zhao Zhiqian (1829–1884) and Wu Changshuo (1844–1927) incorporated the brush technique of the stele school of calligraphy as well as the knife-carving effect of seal carving, into painting and calligraphy. This created the flavour of jinshi (metal and stone) that became very popular. The sense of antiquity based on epigraphy became the “aesthetic vogue of the period”. (Anita Chung, “Reinterpreting the Shanghai School of Painting,” Chinese Paintings from the Shanghai Museum 1851–1911 (Edinburgh: NMS Publishing, 2000), 40.) |

Yeo, Wei Wei, ed. The Story of Yeh Chi Wei. Singapore: National Art Gallery Singapore, 2010. | |

Liu, Kang. “Chi Wei in the Last Ten Years”. Yeh Chi Wei, Singapore, 1969. |