Chinese identity and loyalty in Singapore in the 19th and 20th centuries

It is well known that there has never been only one kind of Chinese identity. This is particularly true of those who left home to settle abroad and had to adapt to different circumstances and different social and political environments. Like migrants everywhere, Chinese have multiple identities, some superficial and momentary, others very deep and permanent. At the personal level, Chinese can choose which identity to emphasise at any one time. They could come from a wide range, from surface identities linked with one’s work, hobby, and social circles, to deep and passionate identities expressed through commitments to family, country, religious faith, or even a political party. Also, different adjectives might be used to characterise their identity. For example: arrogant, cunning, hardworking, backward, superstitious, China-centred. With each of them, various cultural and political judgments were made, and for centuries, most Chinese were powerless to change such labelling and were frustrated by the failure to prove them misleading or wrong.

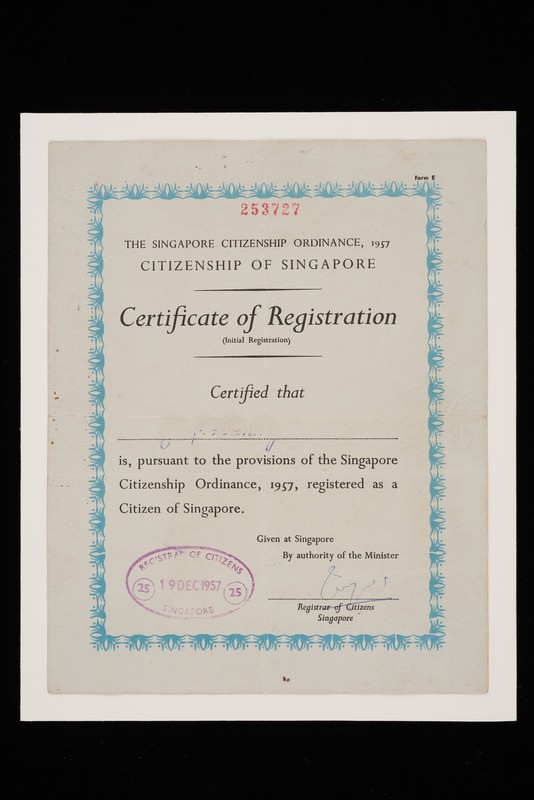

Obviously, self-identity as Chinese could be quite different from being identified by others as someone Chinese. Often, attributes are selectively used, such as a filial son, loyal brother, friend or partner, to describe what was Chinese. These could be used to determine how Chinese someone was. Also, when we speak of different kinds of Chinese, we might expect them to have different identity mixes. For example, there are differences between the Baba and sinkeh; traditionalists and radicals; Chinese-educated and English-educated. We would expect these mixes to emphasise different identities to different peoples and at different times and places. Certainly, there are official and legal identities that cannot be freely challenged. For example, being registered as Chinese at a point of entry to Singapore, in a court of law, or receiving travel papers or permits to set up businesses.

A hierarchy of loyalties

Most people do have more than one identity and are unlikely to have a single unchanging identity all their lives. How, then, does identity relate to loyalty? We can speak of degrees of loyalty as we can of layers of identity. For example, traditional Chinese place loyalty to family above all others, and that could translate to loyalty to the chief, to the prince, to the emperor and all forms of authority. But they also recognised loyalty to friends and partners in any enterprise, and often used kinship terms to describe that. Today, Chinese, like many others, may expect loyalty to country to take precedence over the others. But others would claim that there are loyalties that rise above that. The strongest are values conscientiously expressed that are akin to absolutes in religious faith, followed by assertions of right and wrong, but also where there are clear injunctions to perform certain rites and rituals at specific times. For example, practices in relation to births and deaths, rites of passage, and marriage conditions, that must be respected and may override all other loyalties.

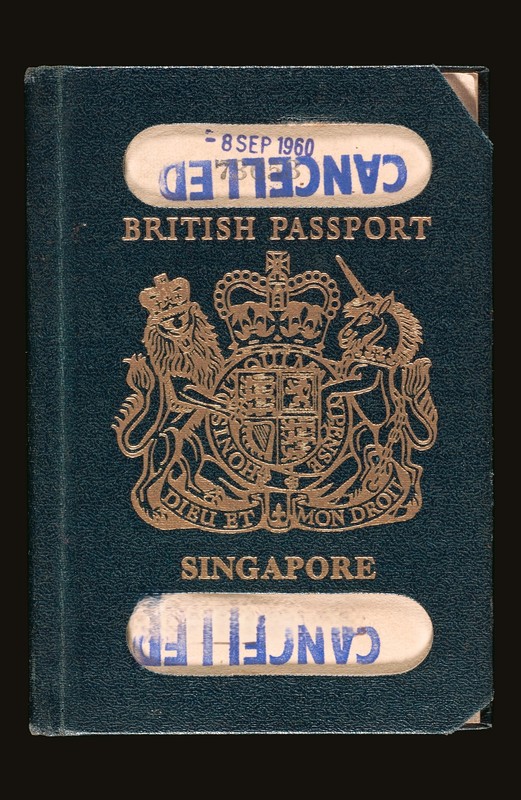

Unlike identity, conflicts of loyalty can be more unyielding. In the two centuries of Singapore’s modern history, some kinds of loyalty have coexisted, like being a British subject and culturally Chinese. Others might include being loyal to a family, to a god or a set of gods, to a secret society or a banned political party. What prevailed was often determined by the exercise of force and law. Most of the time, however, the practices of a plural society allowed some give-and-take and some freedom to choose.

Early years to the 1870s

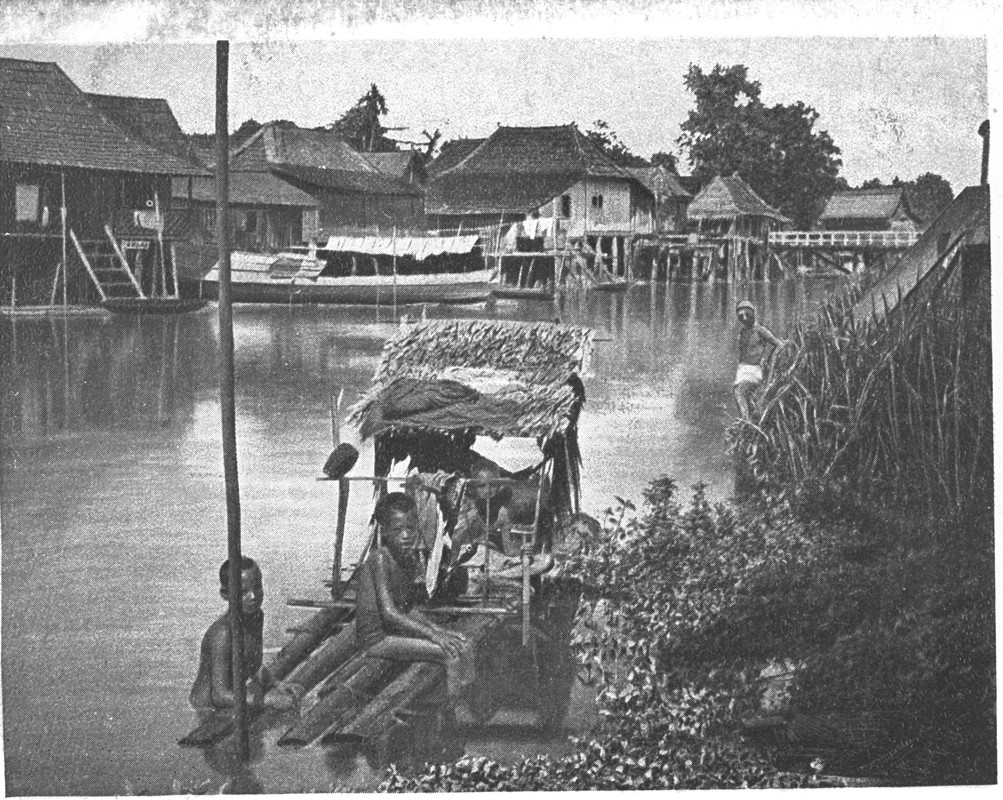

For a few decades, in early history, Singapore was the newest port in the Malay world. The first Chinese who came from that world were largely Baba Chinese who had worked with Dutch and British merchants keenly interested in trading with China. They came largely from Malacca and the nearby islands, and were familiar with the Malay elites, as well as with Anglo-Dutch officials. The British found them invaluable to get the port off to a good start. Most of them were descendants of Chinese men with local wives. They were a closely knit group, proud of their ancestral customs and practices, but did not identify with their homes in China. Others had also been trading and working in the neighbourhood and came to Singapore and received help from Baba Chinese to work here. Theirs was a more localised Chinese culture brought out of their homes in China. They knew their family and village origins and located them in provinces like Fujian and Guangdong, but did not identify with the Qing empire. If anything, they sympathised with those who hated the Manchus and wanted to restore Han Chinese rule.

After the British took Hong Kong and opened up treaty ports in China, many more Chinese spread out in every direction, including thousands who came to Singapore on the way to other islands and the Malay states. Many of them stayed on in Singapore, and they soon outnumbered the earlier Baba Chinese. The British had to learn to differentiate between the varieties of peoples who stressed their different origins and were organised accordingly. The Babas were counted on to be relatively loyal to colonial rule, while the sinkeh, the newcomers, were only loyal to their own kinsmen. Some were active in secret brotherhoods that defended and fought for them. It was also a time when the imperial order in China faced numerous rebellions. The most serious of these, the Taiping Heavenly Kingdom, was exceptionally brutal — not only against Manchu rule, but also against the literati classes, the ruling elites, or even those of Han Chinese origin.1 These rebels generally wanted to upend traditional norms, and when they finally failed in China, many survivors escaped to the Malay world, including to Singapore. They identified with the secret societies, and were usually alienated from any established authority. The Chinese quickly became the majority population in Singapore. It was surprisingly fast, and the British took special measures to ensure that their rival organisations avoided open conflict and respected British laws. A new kind of identity was introduced to the Singapore-born. When any of them traded in China’s treaty ports, British consular services protected them as British subjects. Qing officials — those in Fujian and Guangdong, for example, and even in Shanghai — resented this, and some began to rethink their policy towards the Chinese overseas.

However, it was not until the 1870s that policies were changed and the first consuls were appointed to Singapore, the officials then discovered that the well-established Chinese actually welcomed their offers of protection as subjects of the Qing empire. Thus, some Chinese could now become two kinds of imperial subjects: British and Chinese. Most Chinese were proud to be Chinese, whatever that meant to the British and Dutch and various Malay and Thai rulers, but the idea of being Chinese nationals did not yet arise. Other loyalties still prevailed, such as filial piety to parents, loyalty to immediate family, inherited religious practices and other cultural artefacts, and collectively, to their district or dialect communities. They had no expectations from Qing China. Instead, where the British provided effective governance, some Chinese enjoyed special relations with the colonial authority. Thus, the Chinese lived with multiple identities quite comfortably, and chose which ones to stress when called on. At the same time, there was a hierarchy of loyalties where family would come first, but allegiances to whatever could help their livelihood were also allowed.

British Malaya in the 1870s and beyond

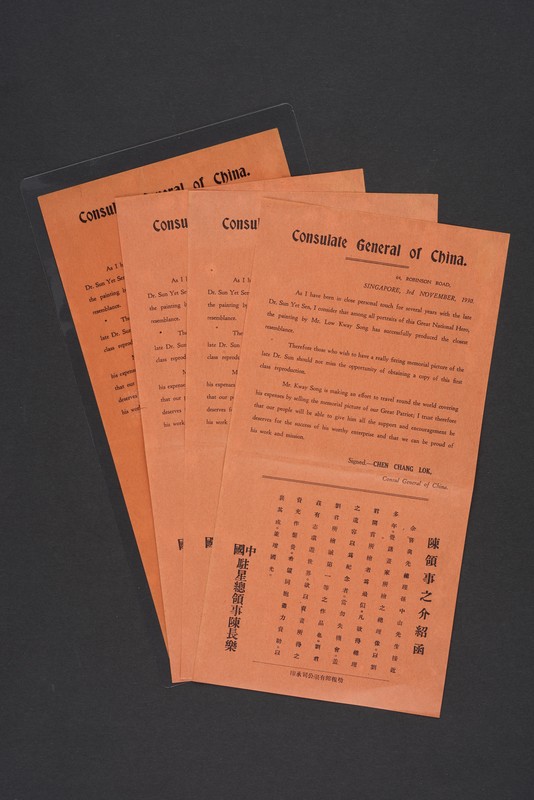

The second period, starting from the 1870s, marked a turning point. For the British, intervention in the Malay states following the Pangkor Treaty (1874) created new regimes of control.2 For the Chinese, the new consulate-general in Singapore, established at about the same time, was a first step in giving them an officially recognised identity. More Chinese were now drawn to British Malaya, and many of them used Singapore as their base. The establishment of a consulate was a reminder that this was a time when the idea that everyone should belong to some nation or another, that idea was spreading around the world. Thus, the Chinese overseas, whether China born or British subjects, were seen as citizens or nationals for the first time, but temporarily living abroad. Hence, the idea of being huaqiao, or Chinese resident temporarily abroad. In that capacity, these Chinese found it increasingly painful to see Qing China continue to weaken and its efforts to modernise and reform being aborted. Some Chinese then openly supported the drive to reject the Manchu and call them foreign rulers, and that gave them a baseline for the growing national awareness. Being Chinese was being redefined using terms that were now hardly distinguishable from those that Japan had adopted from the European nation-states in order to unite the Japanese people. Similar terms were adopted by the Chinese revolutionaries who fought against the Manchus. The pre-national Malay world around Singapore was similarly aroused with this sense of nationality that was spreading everywhere, not least by those who noticed the large numbers of Chinese among them. What being Chinese meant was now questioned at all levels of society by all sections of populations, not least by those who saw them purely as foreign immigrants.

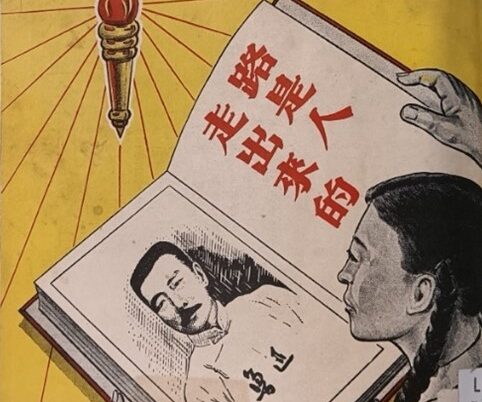

At one end, everyone who originated from China was grouped together as Chinese. This implied a single collective of people. Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925), who lived in Singapore for a while and wanted unity among the Chinese he met, was very unimpressed with this idea that the Chinese were a collective. On the contrary, he compared the Chinese to a large plate of loose sand, unable to cooperate and very difficult to unite. At the other end, Straits Chinese, who claimed to be loyal to the British Empire, contributed money and effort to support empire war efforts ranging from the Boer War to both World War I and World War II.3 In between were men with Baba backgrounds such as Gu Hongming (1857–1928), who discarded what he was taught about modern Western civilisation, and passionately supported the total retention of Confucian traditional values. Others like Lim Boon Keng moved only halfway. He wanted Chinese to be both modern and Confucian at the same time. Yet others were more decisive — a very obvious person to mention is Tan Kah Kee (1874–1961), who aligned his Hokkien culture with national aspirations, and exhorted his compatriots to identify fully with the new China. He was clear what being Chinese meant, and was steadfast in acting as a patriot.

But uncertainty still remained over what defined the Chinese. After the fall of the Manchu Qing empire, a new formula was devised to include everyone within the borders of the former Qing Empire. The term “Five Nation Republic”, or wuzu gonghe, identified the Han, Manchu, Mongol, Muslim Hui, and Tibetans as Chinese, as zhonghua minzu (Chinese people). This is a new term devised at the turn of the century. This new inclusive definition meant that China was nation-building on a different platform altogether, on a very large scale. For those in Singapore who came from southern China, this new construct was rather abstract and remote, so the Chinese Republic launched a massive campaign to re-educate everyone to understand this new formula. The central theme was that the sacred land of China was being cut up and the country dismembered. Including everybody within the borders was the only way to defend the heritage.

Colonial policy encouraged Chinese to bring their families to settle in Singapore, but essentially left them to educate their children. Modern schools sprouted quickly and adopted the Chinese national curriculum. New generations of teachers were inspired by the May Fourth Movement, one of the most radical of the young people in China at the time, and brought their belief that Western, scientific and democratic values could be used to unite China and recover its ancient glory. Newspapers educated the adult population to the power struggles that were occurring all over China by bringing that politics into Singapore. Chinese of all classes began to shape their identities and loyalties in response to this massive education campaign. The British were alarmed and tried to curb what they considered to be excessive nationalist displays. But the alternative that they offered, of becoming Straits Chinese British subjects, promised too little for most Chinese, especially for those who were now politically aroused by what was happening in China. The Baba were also divided — some began to learn the national language and studied things Chinese to affirm their Chinese origins.

National identity was widely asserted when the Nationalist government in China came to power in 1928. When Japanese imperialists created the puppet state of Manchukuo and pushed further inland into northern China, the rising tide of nationalism became overwhelming. Japanese victories in Southeast Asia followed, and the British surrender of Singapore hit the Chinese the hardest. Three years of Japanese occupation forced the Chinese to rethink who they were. It was but a short step from anti-Japanese imperialism to anti-imperialism in general. Most people could now see a post-imperial world of independent states. This placed national identity above all others. The former colonies were ready to start afresh without Europeans in charge. Among Chinese, the numbers of local born had caught up with those born in China, and they looked for new identities and asked what they should now be loyal to. For the post-war economy to recover after the war, law and order was necessary. For the poorer working classes, many were convinced that the time for exploitation was over — the fight for social justice was greatly appealing to most of them. For the young, many more schools were built to prepare them to live as post-colonial nationals, and they began to understand that the polity that replaced British rule would consist of a mix of peoples that looked to different national identities elsewhere — to China, to India, to Indonesia, Melayu Raya, and so on. 4

After the war ended, people in Singapore asked what they could now be. Never before had political identity been defined in narrow national terms. They also had to confront the faded vision of the Malayan Union that the British experimented with. If Singapore were to be included in a communal, dominated Federation of Malaya, there would be further uncertainties. 5 On top of all the layers of ethnic, social and cultural loyalties, the political identity of this Malaya was the central question. Should that state be in the hands of feudal bureaucrats and business classes carrying on the colonial heritage? Should it be a welfare state, as many progressive states, especially in the developed Western world, had become? Or one that chose the revolutionary path, as in China, Vietnam, and even Indonesia? Or should it be a state where ethnic majority dominance determined all issues of identity and loyalty? These questions came up in more and more debates among the people in both Malaya and Singapore. These processes and these questions could not be separated from the larger struggle for global dominance between the United States and the Soviet Union, who then had the Cold War reach out to China and Southeast Asia. Once the Chinese Communist Party won power on the mainland, no Chinese anywhere was immune to the pressure to identify with one side or the other. Political identity, whether based on ideology or ethnicity, began to overwhelm all others.

The nation state and the pluralist ideal

The decades of uncertainty in China and British Malaya, from the late 19th century to the 1960s, saw the challenge of many identities for the Chinese. Singapore was the centre for trade, news, education, and became a node for change among the Chinese in the region. Numerous teachers and journalists kept its Chinese population close to the developments in China. Many official delegations came to Singapore, as did hundreds of political exiles from the civil war between the Guomindang and Chinese Communist Party (CCP). Furthermore, major efforts to raise funds to support the defence of China against the Japanese were inspired by community leaders like Tan Kah Kee. It is now hard to imagine how powerful the pull of China was for most Chinese in Singapore.

Even before the Japanese Occupation, patriotism had become mainstream, and it challenged any residual loyalty to the British and their idea of a pluralist port city. Chinese could see that nationalism had become the most visible and potent political creed. Although many remained firm in their primary concern for family and clan and district associations, the pressure to give priority to national and ideological loyalties continued to grow, particularly in the case of graduates of Chinese high schools. In comparison, many at the English schools tended to identify with modern civic values learnt from Britain, or specific Christian values. Only few admired the national and revolutionary movements in China. It was clear that the products of the two education systems in Singapore were growing apart. The war with Japan narrowed that gap for a while, when Chinese and British interests coincided in the hatred of Japanese militarism. But when the war ended, this was set aside when most of the Chinese educated sympathised with the anti-colonial forces and wanted to see the British leave as soon as possible.

The Chinese remained divided into the 1950s. A small number continued to identify with the politics of China. A larger number engaged in the battle to determine their future in Singapore, but an even larger proportion of them longed for the return of normalcy so that they could protect their businesses and their livelihood and their families. And for this last group, the old formula of loyalty to family and local cultures remained paramount. They understood that Singapore was not China, and could not ever claim to be part of China. They were content to live and work in a plural society, and were ready to go on doing so. In that way, their cultural identity could be preserved, and their children could share their loyalty to what they valued as intrinsically Chinese. As they saw it, what was central was continued access to the Chinese language. This was not only for practical reasons, but also because it gave meaning to their moral and social life.

It was in this context that the campaign for Nanyang University was launched. Once it was clear that high school graduates could no longer pursue their tertiary education in China, the answer was obvious: Singapore should lead the way to build a Chinese-language university. The response, not only in Malaya, but also elsewhere in the region, was overwhelming. In Singapore, Chinese, once again, felt they had a central role in Nanyang and a new kind of transnational Chinese could see Singapore as their base. The British were not prepared to support this in their colony, and non-Chinese political leaders in Singapore shared those concerns. Some feared that Taiwan leaders would use it to nurture and recruit future anti-communist nationalists. Others saw it as a potential seedbed to further radicalise high school graduates who already leant towards the new China.

The founders’ desire to raise language and cultural levels of the Nanyang Chinese was truly deep and genuine. But the anti-communist war in Malaya, the “Ganyang Malaysia” campaign in Sukarno’s Indonesia, and the bitter battles that led to separation and independence for Singapore, conspired to focus attention on the university’s problems rather than its promise.6Its political roles were consequently raised above its educational ideals. Thus, instead of becoming an institution that the Chinese-educated could be loyal to, it stumbled along until it was forced to merge with the University of Singapore, leaving a cultural vacuum that has only been partially mended.

The long and contested decolonisation process after 1945 revealed how much existing national and ethnic identities could threaten the underlying pluralist ideal. Fortunately, most of the younger generation of Chinese education after the war had decided that Singapore was their home. Their Chinese identity was not tied to either the mainland People’s Republic of China or the Republic of China in Taiwan, but was increasingly focused on their cultural heritage. The tumultuous events in China under Mao Zedong merely deepened the distance they felt, and except among a few, being Chinese had nothing to do with communist ideology. Other uncertainties remained, not least those brought by unfriendly elements among Singapore’s neighbours. In that context, the failed 30 September coup — the Gestapu in Indonesia, only weeks after Singapore’s independence — was a stroke of good fortune. When the backlash against the coup destroyed the PKI, the Communist Party of Indonesia, it was a great relief for the new state. The Cultural Revolution in China followed after that, and the horrendous damage it did to Chinese culture and values removed any remaining inclination to admire that China.

Singapore Chinese could now think afresh about the makeup of their country and reflect on the kind of identity and loyalty that could come out of a commitment to what was meant to be a pluralist state. This goal would not be easy to achieve. To define such a national identity not found anywhere else in Asia required very careful and sensitive education for all concerned. The fact that power was in the hands of the Chinese majority in Singapore made it incumbent upon its leadership to ensure that that power was not used to undermine that pluralist ideal. It could not depend on force alone. In the long run, it hinged on building a deep understanding of the equal rights of all Singapore citizens and the guarantee of security among its minorities. Such a commitment demanded open minds, a willingness to compromise, as well as great persuasive skill.

The future of Chinese identity

In the 21st century, conditions are changing as the world adjusts to Chinese economic power. It is timely to ask how Chinese cultural identity in China itself will change, and how that will align with Singapore’s Chinese or national identity.

We have seen what the Chinese overseas in Singapore and elsewhere have been through since the nineteenth century. They have had to change parts of their identities several times and have learnt to manage the chances successfully. From the extreme demands of Chinese nationalism to accusations of being the fifth column of the communist world, from being called hanjian (traitors) by other Chinese to being labelled as alien (pendatang) by local bumiputra, they have been through it all. A deep-rooted pragmatism prevailed as they firmly confronted each kind of crisis and found themselves wiser and enriched by their experience.

There has never been any one Chinese identity, that every has multiple identities. Chinese in Singapore were no exception. Over time, they learnt that Chinese were always diverse and it was in their own interest to acknowledge that diversity. That made most of them accept the norms of plural societies as something they could live with and benefit from.

The second half of the 20th century saw the emergence of new norms for national identity — these expect the people of Singapore, not least the majority Chinese, to construct something beyond having multiple identities and exercising a hierarchy of loyalties. The ingredients for producing a composite Singapore identity seem now present, although it is yet to have an agreed name and such a construct would be contrary to ethnic-based national norms. One would expect it to be an identity that is integrative and distinctively multidimensional, and Chinese experiences in Singapore will have a unique place in shaping that condition – a condition that will allow Singaporeans to say that they are also Chinese.

| 1 | The Taiping Heavenly Kingdom was established in 1851 by Hong Xiuquan (1814–1864), who led the Taiping Rebellion against the Qing dynasty in China between 1850 and 1864. |

| 2 | Also known as the “Pangkor Engagement”, this treaty signed between the British and the local Malay chiefs of Perak effectively marked the beginning of British colonial intervention in the Malay states. |

| 3 | The Boer War was a war between Great Britain and the two Boer republics – the South African Republic and the Orange Free State – which took place from 1899 to 1902. It ended with the Boers accepting defeat. |

| 4 | “Melayu Raya”, meaning “Greater Malay” or “Greater Malaysia” in English, is a political idea in the early 20th century used to signify an enlarged nation incorporating the Malay Peninsula, Java, Sumatra, and other Indonesian islands. |

| 5 | The Malayan Union was formed on 1 April 1946. It included the nine Malay states and the Straits Settlements of Penang and Malacca, while Singapore became a separate crown colony. |

| 6 | On 25 September 1963, President Sukarno (1901–1970) announced a “Ganyang Malaysia” or “Crush Malaysia” campaign during the Indonesia-Malaysia Confrontation period (commonly known as “Konfrontasi”), which escalated to open cross-border military attacks against Malaysia and Singapore. |

Chan, Ying-kit and Hoon, Chang-Yau. Southeast Asia in China Historical Entanglements and Contemporary Engagements. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2022. | |

Ho, Elaine. Citizens in Motion: Emigration, Immigration, and Re-migration Across China’s Borders. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2018. | |

Kuhn, Philip A. Chinese Among Others: Emigration in Modern Times. Singapore: NUS Press, 2008. | |

Wang, Gungwu. China and the Chinese overseas. Singapore: Times Academic Press, 1991. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Dongnanya yu huaren: Wang Gengwu jiaoshou lunwen xuanji [Southeast Asia and the Chinese: Selected papers of Professor Wang Gungwu]. Beijing: China Friendship Publishing Company, 1987. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Nanyang: Essays on Heritage. Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, 2018. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Living with Civilisation: Reflections on Southeast Asia’s Local and National Cultures. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2023. | |

Wang, Gungwu. Roads to Chinese Modernity: Civilisation and National Culture. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2025. | |

Wang, Gungwu. The Chinese Overseas: From Earthbound China to the Quest for Autonomy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000. |