Chinese Muslims in Singapore

Chinese Muslims have long been a small but distinctive minority in Southeast Asia, shaped by centuries of migration, trade, and cultural exchange. In Singapore, they represent about 0.5% of the population, numbering approximately 12,000 individuals as of 2020. While the rest of Chinese Singaporeans identify as Buddhist (40.4%), Taoist (11.6%), Christian (21.6%), or having no religious affiliation (25.7%).

Spread of Islam and the formation of Muslim communities in China

The history of Islam in China dates back to the 7th century, during the Tang dynasty. Visits from Arab envoys, scholars, merchants and businessmen brought about the spread of Islam in China. Southern port cities in China, such as Guangzhou, Fuzhou and Quanzhou, became major hubs for Arabian and Persian traders who entered China by sea to trade. These traders married local women and settled in China, forming the earliest Chinese Muslim communities. By the early 13th century, more Muslims, mainly Arabs, Persians, and various ethnic groups from Central Asia, migrated to the interior of China, spreading Islam nationwide. Many became officials and controlled major sea trading routes.1 Of the 56 ethnic groups in China, 10 practice Islam.

Over the centuries, many Chinese Muslims migrated to Southeast Asia. A significant piece of evidence of their early presence in the region is a tomb from the Song dynasty (960–1279), located in present-day Brunei. This tomb belonged to Pu Zongmin (birth and death years unknown), a high-ranking minister of Arab Muslim descent from Quanzhou, China. Pu Zongmin was sent on an official mission to “Puni”, the historical name for Brunei during the Song dynasty, where he eventually died.

A major wave of Chinese Muslim migration to Southeast Asia began in the late Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), and was fuelled further by wars and discriminatory measures introduced in the early Ming dynasty (1368–1644). In 1372, Ming emperor Taizu issued a decree that banned endogamy within the Mongolian and Muslim communities and required them to intermarry with the Chinese. Those who did not follow the rules would be caned and sent to the imperial palace as servants. In 1385, Muslims were expelled from Guangdong, forcing many to go into exile and seek opportunities in Southeast Asia.2

The most famous examples of contact between Chinese Muslims and people in Southeast Asia would be Admiral Zheng He’s voyages between 1405 and 1433 during the Ming dynasty. Zheng He, born in Yunnan to a Hui family, led seven expeditions to Southeast Asia and beyond. Accompanied by Ma Huan, who later authored Yingya shenglan (The Overall Survey of the Ocean’s Shores), Zheng He contributed to the growth of Chinese Muslim communities in the Southeast Asia region by helping them establish places of worship and other buildings.

Early Chinese Muslims in Singapore

By the 19th and 20th centuries, Chinese Muslims had an established presence in various parts of Southeast Asia, including Singapore. In 1908, Mohammed Djinguiz (birth and death years unknown) published Revue du Monde Musulman (Review of the Muslim World). In it, he reported that there were 4,920 Chinese Muslims in Singapore, constituting 3% of the total Chinese population at the time.3

Singapore emerged as a hub for Chinese Islamic publications in the early 20th century, nurturing prominent authors who were pioneers of Muslim Chinese literature. One of them was Shamsuddin Tung Tao Chang (1920–1995), who graduated from Fudan University. Shamsuddin moved to Singapore in the 1950s before relocating to the United States in 1979. During his time in Singapore, he was the chief writer for Sin Chew Jit Poh and the editor-in-chief of Nanyang Siang Pau. He wrote columns on Yisilan qianyi (Introduction to Islam) and published Kexue de huijiao (Scientific Islam) that helped introduce Islam to the Chinese community. His works featured a combination of classic Islamic literary quotations with Chinese folk proverbs and poetry.4

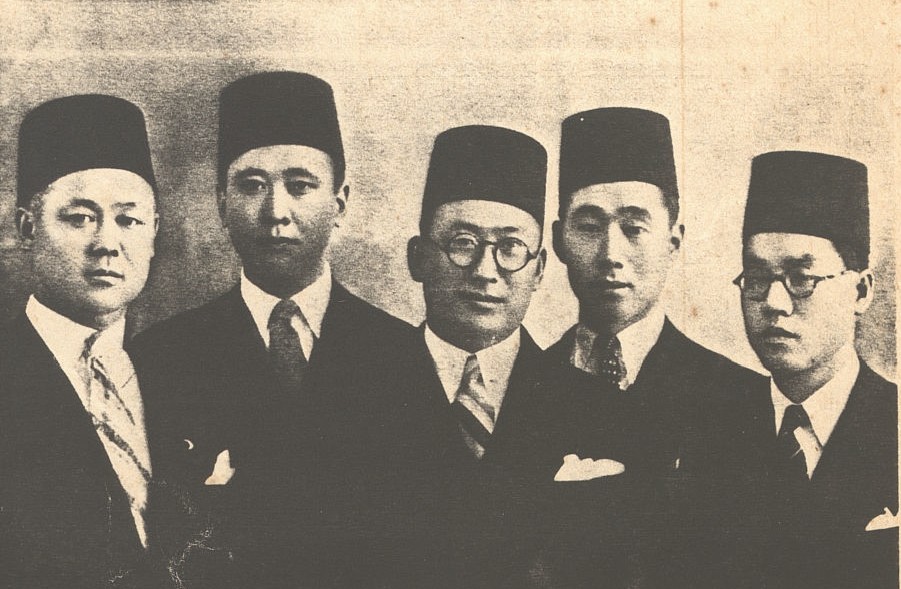

The family of Haji Ibrahim Ma Tien Ying (1900–1982) also played a pivotal role in advancing Islamic knowledge among the Chinese in Singapore and Malaya. Haji Ibrahim Ma Tien Ying was a Consul General of Ipoh sent by Kuomintang in 1948. He first came to Malaya between 1938 to 1940 as head of the three-member Chinese Muslim Goodwill South Seas delegation. Their tour, which included Singapore, allowed the locals to gain firsthand insights into Islam practices in China and inspired at least 30 Chinese in Singapore to embrace the Muslim faith. Throughout his life, he published numerous Chinese publications about Islam, such as Yisilanjiao wenda (Questions and Answers on Islam), Weishenme musilin bu chi zhurou (Why Muslims Don’t Eat Pork), Yisilan jiaoyi yu zhongguo chuantong sixiang (The Teachings of Islam and Traditional Chinese Philosophy).5 These seminal publications in Chinese helped to foster understanding between Muslim and non-Muslim communities in the region.6

After his death, his eldest daughter Aliya Tung Ma Lin (1925–2018) — a prominent author in Muslim Chinese literary circles — continued his work. Aliya moved to Singapore around the 1950s and was a member of the Singapore Association of Writers. Among her many published works were Yiwei funü dui musilin meide de yi pie (A Woman’s Glimpse of Muslim Virtues) and Ma Tianying zhuan (Biography of Ma Tianying), which contemplated the development of Islam and its religious doctrine from a Chinese woman’s perspective.7

Aside from literary contributions, Chinese Muslims also played significant roles in community building. In 1940, the Sino-Muslim Cultural Association of Malaya (Singapore) was formed to promote greater understanding between Chinese and Muslims. This happened after a meeting at the Chinese Chamber of Commerce, which was attended by prominent Chinese and Muslims — including the Chinese Islamic South Asia Goodwill Delegation — and presided over by the chamber’s president Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957).8

An individual of Hui descent who has contributed much to the community is Mohd Salleh Mah Soo Lan (birth and death years unknown) and Jaafar Mah (1949–2021). Mohd Salleh Mah Soo Lan established a thriving dairy business called Salleh’s Baby Brand Condensed Milk and opened the first Chinese Muslim restaurant at the New World Amusement Park (no longer in operation). Jaafar Mah is the son of Mohd Salleh Mah Soo Lan. Similar to his father, he is also a successful businessman and set up a food catering business called Spice Village. In 2019, he contributed to the establishment of the Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore to serve the needs of Chinese Muslims in Singapore.9

Chinese Muslim associations and practices

Today, Chinese Muslims in Singapore have forged an identity that blends Chinese cultural traditions with Islamic practices. Like other Muslims in Singapore, they observe the Five Pillars of Islam, which form the foundation of their faith. These include the declaration of faith (shahada), performing the five daily prayers (solat), giving alms to the needy (zakat), fasting during the month of Ramadan (puasa), and undertaking the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj) if they are able. They also actively participate in communal Friday prayers (solat Jumaat) at mosques.

Alongside Islamic practices, Chinese Muslims in Singapore uphold their linguistic and cultural heritage, speaking Chinese dialects and celebrating key Chinese festivals such as Lunar New Year, Chap Goh Mei, and the Mid-Autumn Festival. This dual heritage extends to their culinary and social practices, particularly during festive periods. During Lunar New Year, for example, halal versions of traditional Chinese dishes are prepared, allowing families to enjoy familiar flavours while adhering to Islamic dietary laws. Similarly, Islamic festivals such as Hari Raya Aidilfitri (Eid al-Fitr), marking the end of Ramadan, and Hari Raya Aidiladha (Eid al-Adha), associated with the annual pilgrimage to Mecca, are celebrated with devotion and communal gatherings. These festivals often incorporate elements of Chinese cultural traditions, such as the exchange of red packets (angbao).

This fusion also adapts traditional Chinese dishes to comply with Islamic dietary requirements, substituting non-halal ingredients like pork and alcohol with permissible alternatives. For instance, bak kut teh, traditionally a pork rib soup, is reimagined using halal meat to create a flavourful alternative. Halal dim sum, featuring items such as chicken-filled dumplings and beef siu mai (small dumplings typically made of ground pork), provides bite-sized delights suitable for Muslim diners. Additionally, dishes from Lanzhou, such as the renowned Lanzhou beef hand-pulled noodles, naturally align with halal standards as they originate from the Muslim-majority Hui community in China.

In Singapore today, there are two cultural organisations serving the Chinese Muslim community: the Muslim Converts’ Association of Singapore (MCAS, or the Darul Arqam) and Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore.

The MCAS, founded in 1979, is a Singapore-based non-profit organisation, formed as a place where new Muslim converts could get together and develop fraternal, religious, and social relationships. They offer services to aid and educate new Muslims, such as classes on Islamic culture and religion, financial assistance for religious activities, and social gatherings to promote fellowship. MCAS also covers the nuances of the minority experience in a primarily non-Muslim society, such as dealing with religious diversity and learning to foster tolerance between different cultures and religions within families. The group has done much to encourage recent converts to feel welcome and accepted upon their conversion, helping them develop essential ties with other members of the community that go far beyond religious teachings.10

The Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore was formed in 2019 to revive and maintain the rich history of Chinese Muslim culture. It also promotes social harmony by inviting families of mixed marriages to participate in festivities.11

| 1 | Liao Dake, Zhenghe yu dongnanya huaren musilin. |

| 2 | Ma Hailong, “The history of Chinese Muslims’ Migration into Malaysia.” |

| 3 | Rosey Wang Ma, “Chinese Muslims in Malaysia: History and development.” |

| 4 | Yang Jianjun, “Dongnanya huizu huawen wenxue de fazhan gaikuang”. |

| 5 | “Chinese Muslims in Malaysia: Haji Ibrahim Ma Tian Ying.” |

| 6 | Yang Jianjun, “Dongnanya”. |

| 7 | Yang Jianjun, “Dongnanya”. |

| 8 | Tribune Staff Reporter, “Consolidating the two communities.” |

| 9 | “Mah’s family biography,” from Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore website. |

| 10 | “History,” from Muslim Converts’ Association of Singapore website. |

| 11 | “Inception of Hui Hui,” from Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore website. |

“Chinese Muslims in Malaysia: Haji Ibrahim Ma Tian Ying.” Biniku Mualaf. | |

“History.” Muslim Converts’ Association of Singapore. | |

“Inception of Hui Hui.” Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore. | |

“Mah’s Family Biography.” Hui Hui Cultural Association of Singapore. | |

Liu, Yusuf Baojun, Haji. A Glance at Chinese Muslims. Kuala Lumpur: Malaysian Encyclopedia Research Center Berhad (Pusat Penyelidikan Ensiklopedia Malaysia), 1998. | |

Liao, Dake. “Zhenghe yu dongnanya huaren musilin” [Zheng He and Chinese Muslim in Southeast Asia]. Jinan Journal 27/6 (2005): 123–127. | |

Lim, Sakinah Arif. “Deconstructing Identities: The Case of Chinese Muslims in Singapore.” PhD diss. Singapore: National University of Singapore, 2022/2023. | |

Lin, Meiling. “Bendi huazu huijiao tu qiju qingzhu kaizhaijie” [Local Chinese Muslims gather to celebrate Hari Raya (Eid al-Fitr)]. Lianhe Zaobao, 10 April 2024. | |

Ma, Hailong. “The history of Chinese Muslims’ migration into Malaysia.” Dhul Hijjah 1438, 2017. | |

Ma, Rosey Wang. “Chinese Muslims in Malaysia: History and development.” | |

Tribune Staff Reporter. “Consolidating the two communities.” Malaya Tribune, 16 March 1940. | |

Wu, Ridzuan. Reflections of a Chinese Muslim. Kuala Lumpur: Regional Islamic Da’wah Council of Southeast Asia, 2017. | |

Yang, Jianjun. “Dongnanya huizu huaren wenxue defazhan gaikuang” [Chinese Muslim literature in Southeast Asia]. Journal of Beifang University Of Nationalities 1 (2016): 83–87. | |

Yang, Wenting. “Huilihui: Jinnian gengduo bendi huazu guiyi huijiao” [MUIS: In recent years, more local Chinese have converted to Islam]. Lianhe Zaobao, 28 June 2023. |