See Ewe Lay and Lat Pau

Lat Pau was first published on 10 December 1881 and continued running till 31 March 1932. This remarkable record of 50 years and 4 months made it the longest-running Chinese-language newspaper in Singapore before World War II. The newspaper’s enduring legacy has been largely attributed to its chief editor Yeh Chih Yun (1859–1921). Less widely known, however, is the fact that Lat Pau was founded by an English-educated Peranakan businessman, See Ewe Lay (1851–1906). See was born to a prominent Peranakan (Straits Chinese) family. His grandfather, See Hoot Kee (1793–1847), was a pioneer in the Hokkien community of Singapore.

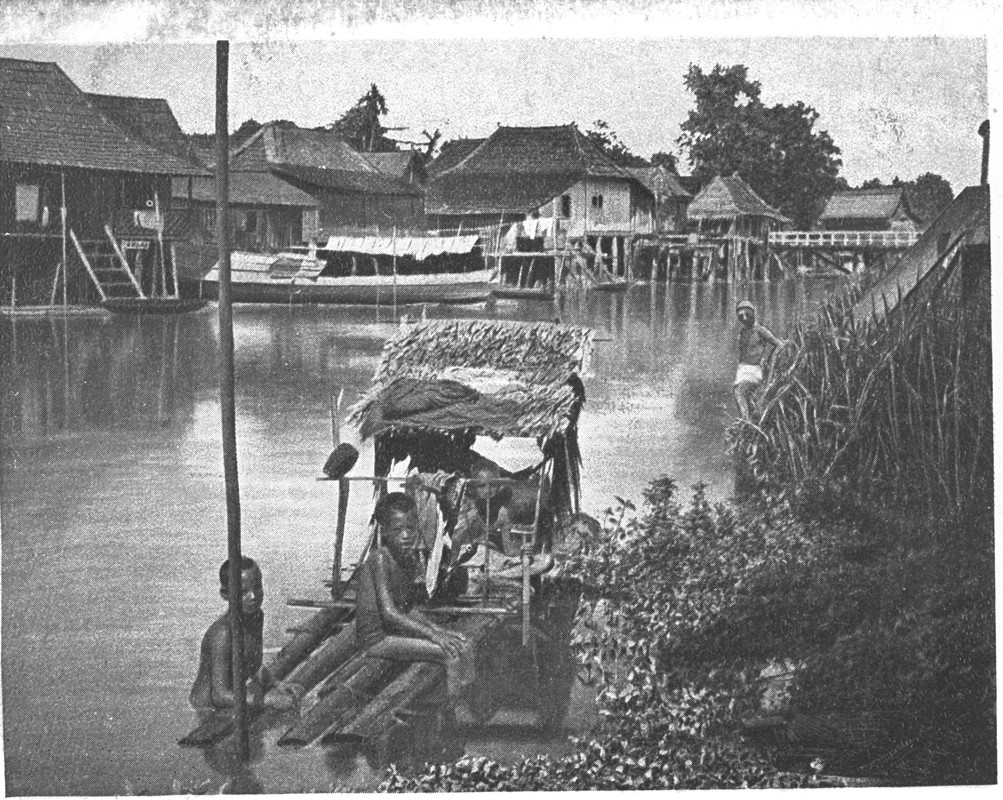

The early Peranakans’ strong identification with Chinese culture could have been a motivating factor behind See Ewe Lay’s founding of Lat Pau. Exhibits at the Baba & Nyonya Heritage Museum in present-day Malacca show how Chinese culture influenced every aspect of the daily lives of the 19th century Straits Chinese, including domestic routines, festivities, weddings and funerals. The See family also had frequent contact with China. See Ewe Lay’s father, See Eng Wat (1826–1884), ran a shipping business and frequently travelled between Singapore and Xiamen, China. See Ewe Lay’s younger brother, See Ewe Hock (Sit Yau Fu, 1862–1884), served in the Fujian Marine Fleet and died during the Battle of the Pagoda Anchorage in 1884.

Growing circulation numbers

To focus on publishing the newspaper, See Ewe Lay resigned from his well-paid comprador position at the Hongkong and Shanghai Banking Corporation. He also declined an invitation from the colonial government in 1892 to become a Municipal councillor. However, during the early years of its publication, with limited literacy among the population, Lat Pau struggled to find readers, and its average circulation was less than 350 copies per year. In 1890, the threat of closure loomed large.

| Year | 1883 | 1884 | 1885 | 1886 | 1887 | 1888 | 1889 | 1890 |

| Circulation (Copies) | 350 | 301 | 300 | 300 | 168 | 200 | 200 | 200 |

See Ewe Lay did not let these financial losses deter him. He hired Yeh Chih Yun, then editor of Hong Kong’s Chung Ngoi San Po (Chinese and Foreign Gazette), to take charge of the editorial work for Lat Pau, which gave the newspaper a significant boost. See Ewe Lay described his mission as one to “enlighten the people”. This philosophy aligned well with the ideals of his grandfather, See Hoot Kee, even though the younger See had never met his grandfather in person. With See Ewe Lay’s strong sense of cultural mission, Lat Pau managed to survive despite the financial losses during its early days.

After more than a decade from its inception, Lat Pau saw a gradual increase in circulation, reaching around 500 copies per year by 1900. Over its more than 50 years of publication, Lat Pau preserved the history of Singapore’s early Chinese community, providing invaluable source material for scholars researching the local Chinese community. The newspaper’s format served as a model for future Chinese newspapers, and its supplement was the start of newspaper’s supplements in Singapore’s history. Lat Pau holds an indelible place in the history of Chinese publications in Singapore.

This is an edited and translated version of 薛有礼与《叻报》. Click here to read original piece.

“Benbao chushi sanshi zhounian jinian xu” [A note on our 30th anniversary edition]. Lat Pau, 11 December 1911. | |

Chen, Mong Hock. The Early Chinese Newspapers of Singapore 1881–1912. Singapore: University of Malaya Press, 1967. | |

Kua, Bak Lim. “Xuefoji jiazu dui xinhua shehui de gongxian” [The contributions of See Hoot Kee’s family to Singapore Chinese society]. In Shile shiji [The History of Silat], edited by Kua Bak Lim, 65–73. Singapore: The Youth Book Co., 2007. | |

Kua, Bak Lim. “Xue shi jiazu, le bao, min bang wenhua” [See family, Lat Pau, Hokkien community culture]. In Shijie Fujian mingren lu, xinjiapo pian [Prominent Figures of the World Fujian Communities — The Singapore Chapter], edited by Kua Bak Lim, 318–327. Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 2012. | |

Lat Pau. National University of Singapore Digital Gems Collection. | |

Song, Ong Siang. One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore: The Annotated Edition, annotated by Kevin Y. L. Tan. Singapore: National Library Board and World Scientific, 2020. First published 1923 by John Murray (London). | |

Tan, Bonny Muliani. “Lat Pau (Le Bao)”. Singapore Infopedia. |