Hokkien clan associations in Singapore

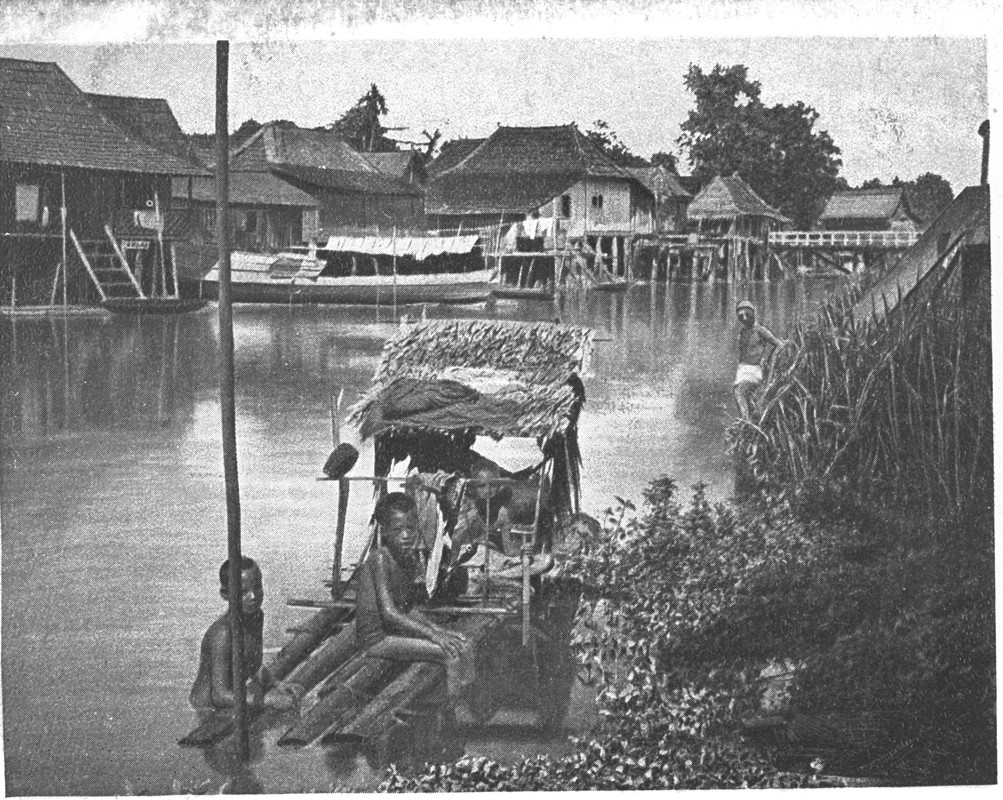

The earliest Hokkien immigrants in Singapore were descendants of Hokkiens from Minnan, or China’s Southern Fujian province, who had lived in Malacca for decades. These Malaccan Hokkiens arrived in Singapore even before the Hokkien immigrants from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou. The Malaccan Hokkiens had a competitive edge as they were among the first to learn about Raffles’ intention to transform Singapore into a free port (which came to pass in 1819). Recognising the immense opportunity at hand, the Malaccan Hokkien community moved swiftly to Singapore under the leadership of pioneer See Hoot Kee (1793–1847), bringing in capital to exploit these new market prospects.

By 1828, they had already founded the Heng San Teng (also known as Heng San Ting or Heng Suah Teng) cemetery temple in Singapore. Modelled after the Cheng Hoon Teng and Poh San Teng cemetery temples in Malacca, the Heng San Teng cemetery temple was more than a place of worship — it was a vital and earliest-established institution that catered to the Hokkien community’s livelihood and welfare. It also led and represented the Hokkien community in Singapore. While Heng San Teng did not officially promote itself as a clan association (also known as huiguan or huay kuan), it fulfilled roles reminiscent of the early clan associations.

Hokkien Huay Kuan and Thian Hock Keng

In 1839, See Hoot Kee stepped down from his leadership position and returned to Malacca, where he later took charge of the Cheng Hoon Teng cemetery temple. That same year, another figure from Malacca, Tan Tock Seng (1798–1850), rose to prominence as the new leader of the Hokkien community in Singapore. Under his leadership, Hokkien merchants came together to build Thian Hock Keng temple on Telok Ayer Street. Completed in 1842, this temple complex was dedicated to Mazu — the Mother of Heavenly Sage and the Goddess of the Seas. Community leaders aspired to use the worship of Mazu as a unifying force for the diverse Chinese communities in Singapore, and stone steles installed in the temple in 1850 carry inscriptions that document this vision. Tan Tock Seng and other temple directors referred to themselves as “Tang people” (tangren) — a term that applies to the broader Chinese community, transcending individual dialect groups or places of origin. The inscription also suggests that Thian Hock Keng, in addition to being a temple, functioned as a clan association that represented the community and cared for its well-being.

In time, the Hokkien Huay Kuan relocated from Thian Hock Keng temple and established its own building just across the street, where a street opera stage used to be. Until 1929, the Hokkien Huay Kuan was helmed by See Tiong Wah (1886–1940) — a direct descendant of See Hoot Kee — and managed by a handful of Hokkien community leaders. The period from 1929 to 1949 was a transformative time for the Hokkien Huay Kuan. Under the stewardship of Tan Kah Kee (1874–1961), the association enhanced the educational standards and opportunities for the Chinese community in Singapore. There were also significant reforms to the association’s structural organisation. Furthermore, the association expanded the business prospects for the Chinese community, and initiated reforms in funeral rites and traditions. It was also under Tan Kah Kee’s leadership that the association made significant contributions to China’s disaster relief initiatives as well as resistance efforts against Japanese aggression during World War II. This era thus marked the transformation of the Hokkien Huay Kuan from a parochial, clan-based organisation to one with broader objectives. It not only represented and unified the Hokkiens in Singapore, but extended its influence over the various Chinese communities in the Malaya and across Southeast Asia. Through these endeavours, Tan Kah Kee was acknowledged as the preeminent leader of the Chinese communities in Singapore and Malaya.

In the meantime, Hokkien immigrants from different Fujianese counties in China also ventured to Singapore in large numbers. They founded their guilds or clan associations grouped around local or regional identities.

List of locality-based Hokkien clan associations

- Eng Choon Hway Kuan (1867)

- Singapore Foochow Association (1909)

- Singapore Futsing Association (1910)

- Singapore Jin Hoe Lian Ghee Sia (1910)

- Singapore Chin Kang Huay Kuan (1918)

- Hin Ann Huay Kuan (1920)

- Singapore Ann Kway Association (1922)

- Singapore Thor Guan Club (1923)

- Singapore Hui Ann Association (1923)

- Lam Ann Association (1926)

- Ho San Kong Hoey (1928)

- Chang Chow General Association (1929)

- Tung Ann District Guild (1931)

- Chao Ann Association (1936)

- Lung Yen Hui Kuan (1938)

- Leong Khay Huay Kuan (1939)

- Phor Tiong Koh Peng Association (1947)

- Singapore Oh Hong Sia Association (1948)

- An Hai Association (1948)

- Chuan Koon Kang Kong So (1948)

- Gnoh Kung Association (1953) (Relocated to the premises of Kim Mui Hoey Kuan, 1988)

- Pho Chen Huay Kuan (1957)

- Bukit Panjang Hokkien Kong Huay (1958)

List of kinship-based Hokkien clan associations

- Singapore (Ji Yang) Cai Clan Association (1866)

- Singapore Lam Ann Loh Khoe Ng Shi Association (1947)

- Singapore Hokkien Yeo See Association (1950)

- Foochow Hoon Clan Guild of Singapore (1956)

- Singapore Futsing Tung Chiang Clansmen’s Association (1964)

- Singapore Hokkien Ong Clansmen General Association (1967) (Traces back to Hokkien Ong Ancestral Temple, founded in 1875)

Most of these locality and kinship-based associations were established in Singapore during the British colonial era. They saw close collaboration between regular Hokkien immigrants, as well as their community leaders who shouldered the responsibility of creating jobs, supporting livelihoods, and managing funeral rites. These associations thus came to be the highest body for Hokkien communities in Singapore away from their ancestral homes. They also played the important role of preserving Chinese culture, making Singapore a home with familiar traditions from immigrants’ homelands.

After Singapore gained independence, the new government took over many of the roles once fulfilled by clan associations. The clan associations thus shifted their focus to local concerns, including education and the promotion of Chinese cultural heritage.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡闽帮会馆文化. Click here to read original piece.

Dean, Kenneth and Hue, Guan Thye, eds. Chinese Epigraphy in Singapore 1819–1911. 2 Vols. Singapore & Guangxi: National University of Singapore Press and Guangxi Normal University Press, 2017. | |

Lim, How Seng et al. Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat]. Singapore: South Seas Society, 1975. | |

Song, Ong Siang. One Hundred Years’ History of the Chinese in Singapore: The Annotated Edition, annotated by Kevin Y. L. Tan. Singapore: National Library Board and World Scientific, 2020. First published 1923 by John Murray (London). | |

Chen, Ching-ho and Tan, Yeok Seong, Xinjiapo huawen beiming jilu [A Collection of Chinese inscriptions in Singapore]. Hong Kong: The Chinese University of Hong Kong Press, 1972. |