Traditional trades of the Hainanese community in Singapore

The Hainanese had fewer job options as they arrived in Singapore later than other dialect groups. As a result, they could only take up relatively strenuous jobs, such as cooks or domestic helpers in European or wealthy Peranakan Chinese households. The Hainanese would know which households were looking for domestic helpers, and get their clansmen to apply for the jobs. Over time, working for European families became a common job among the Hainanese. There was a clear division of labour between male and female domestic helpers, with the men taking care of the houses and women looking after the employers’ children.

Middle Road, Purvis Street, and Seah Street, colloquially known as “Hainan First Street”, “Hainan Second Street”, and “Hainan Third Street” respectively, were favourite haunts of the Hainanese on their days off. This is when they would catch up with one another in dormitories located in the area, enjoy Hainanese food at coffee shops and restaurants, as well as send money and letters back to their homes in China through remittance bureaus.

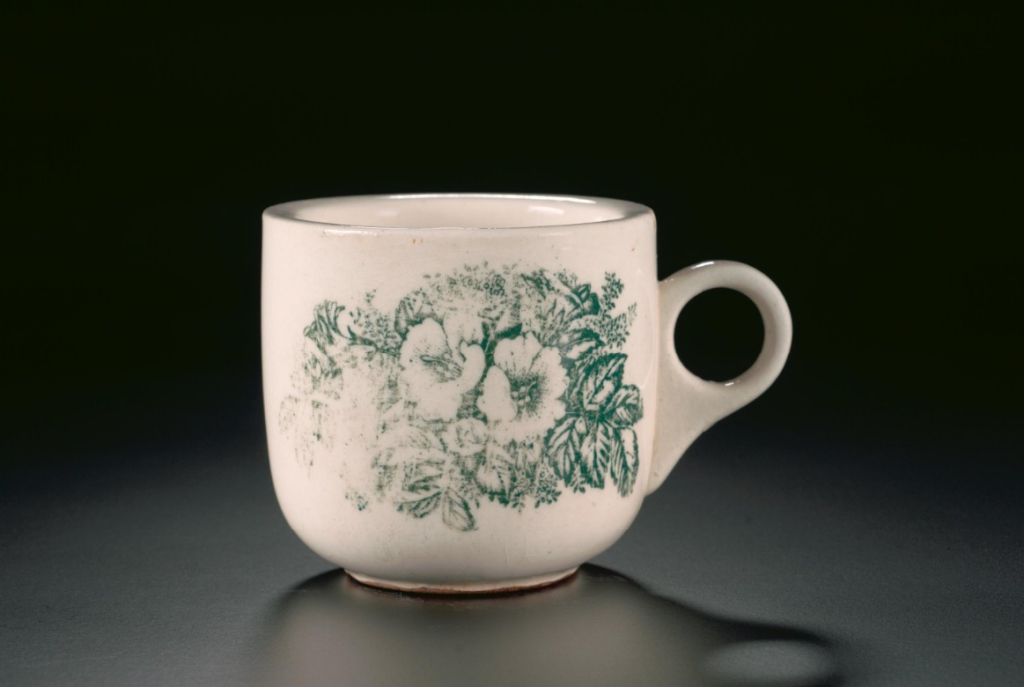

Coffee shops and bakeries

In the old days, coffee shops in Singapore were mostly run by the Hainanese and Foochows (Hockchews). From the 1920s to early 1930s, when the global economy plunged into the Great Depression, many Japanese sold off their hotels in shophouses along Beach Road and the three Hainan streets. A number of Hainanese also sold their rubber plantations in Johor and moved to Singapore, bought over these shophouses from the Japanese, and turned them into coffee shops. This was the golden era of Hainanese-run coffee shops. The short “Hainan First Street” alone had five coffee shops, while there were seven coffee shops along “Hainan Second Street” and three on “Hainan Third Street”. According to historical records, there were 195 coffee shops run by the Hainanese in Singapore in 1927.1

After the end of World War II in 1945, the Hainanese were running fewer coffee shops than the Foochows. According to data from 1949, out of the coffee shops holding a government business licence, 664 were run by the Foochows, and 467 by the Hainanese.

One main reason for the trend was the lack of successors among the Hainanese. Many of these coffee shops were family businesses, and after two generations, the third generation was usually not keen to take over the business as most of them were well-educated and aspired to spread their wings elsewhere. Hence, many coffee shops operated by the Hainanese were sold to the Foochows. Today, Hainanese and Foochow coffee shop operators still have their own associations. The Singapore Foochow Coffee Restaurant and Bar Merchants Association, founded in 1921, and the Kheng Keow Coffee Merchants, Restaurants and Bar-owners Association, which was set up in 1934, take turns to hold the annual Chinese New Year gathering to maintain friendships among those in the same trade.

Among the traditional coffee shops run by the Hainanese, Keng Wah Sung at Lorong 41 Geylang still preserves the flavour of yesteryear.

Besides coffee shops, many Hainanese also operate bakeries. Four of the better-known ones are located near North Bridge Road: Jong Juan Fang on Bencoolen Street, Ban Hup Hong on Queen Street, Red House at the corner of Victoria Street, and Xie Yu Long on Rochor Road. Before these bakeries closed down, bread consumed by people in the city area was made by these bakeries.

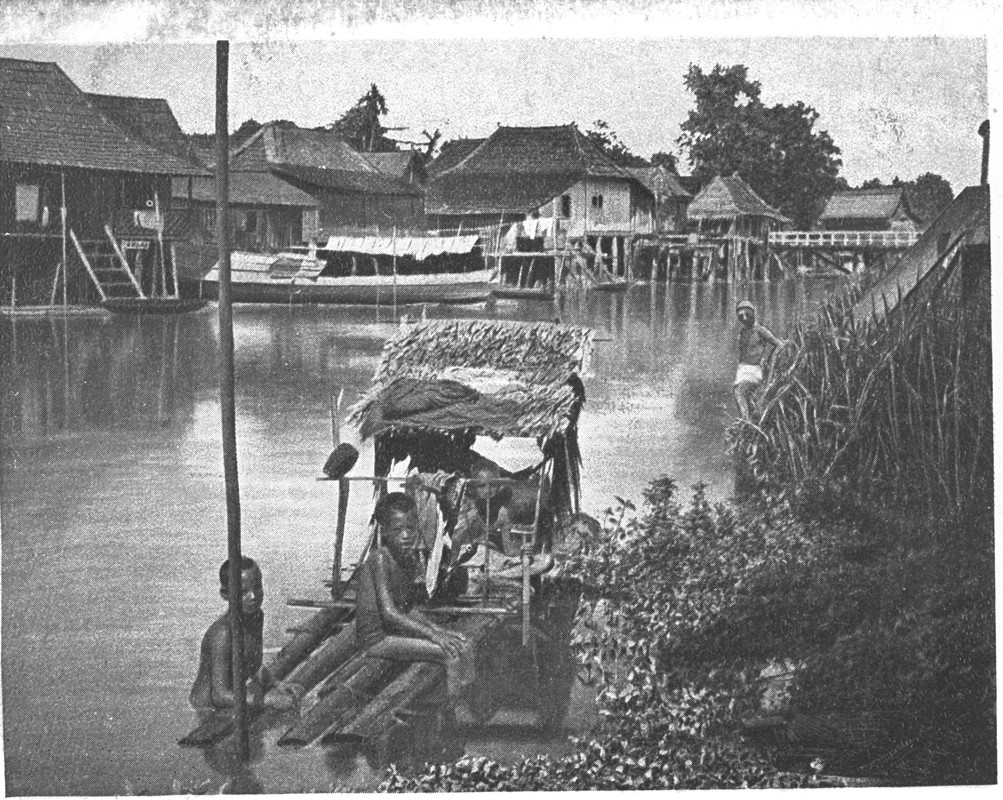

Many Hainanese were also seafarers, who were mostly introduced to the trade by people from their hometown. Some were in charge of the locomotives on board, while others worked as cooks or waiters. The dormitories mentioned earlier were home to many Hainanese seamen. They often stayed in dormitories when they were back on land, and went out to sea again when there were job openings on the ships. The dormitories provided them with a roof over their heads even when they were jobless.

The Hainanese worked hard not only to support their families, but also to give back to their community. After making their fortunes, many Hainanese donated to rural schools which helped to nurture the children of many of their clansmen.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡海南人的传统行业. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Ong Siew Peng quoted from Yun Yumin’s Xinjiapo qiongqiao gaikuang [An overview of Hainanese immigrants in Singapore] (1931). See Ong Siew Peng, “Xinjiapo hainan ren de kafei dian ye” [The coffee shop business of Hainanese in Singapore], Malaysia Singapore Coffee Shop Proprietors’ General Association website. |

Ong, Siew Peng. “Xinjiapo hainan ren de kafei dian ye” [The coffee shop business of Hainanese in Singapore], Malaysia Singapore Coffee Shop Proprietors’ General Association website. | |

Ong, Siew Peng. Oral history interview by Jesley Chua Chee Huan, 22 January 1991, audio, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 001210), Reel/Disc 6–15. | |

Wong, Chin Soon. Jiyi li de xiaopo [Memories of the North Bridge Road area]. In Gen de xilie [The roots series], v 7. Singapore: The Youth Book Co., 2005. | |

Wong, Chin Soon. Hua shuo hainan ren [Speaking of Hainanese people]. In Gen de xilie [The roots series], v 9. Singapore: The Youth Book Co., 2008. | |

Wong, Chin Soon. Hua shuo mituo lu [Speaking of Middle Road]. In Gen de xilie [The roots series], v 14. Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2021. | |

Wong, Chin Soon. Zuori hainanjie [Hainan Street of yesterday]. In Gen de xilie [The roots series], v 15. Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2023. | |

Wong, Chin Soon. “Hainan ren de huidui jie: Yi dai ren de jiti huiyi” [Remittance services on Purvis Street: A collective memory of the Hainanese]. Lianhe Zaobao, 20 April 2023. | |

“Xinjiapo hainan ren gongxian” [Contributions of Hainanese in Singapore], The Singapore Hainan Hwee Kuan website. | |

Zhou, Wenpei. “Kuaguo zhuyi yu xinjiapo qiongren” [Transnationalism and Hainanese in Singapore]. PhD diss., School of Humanities, Nanyang Technological University, 2020. |