Traditional trades of the Hokkiens in Singapore

Since the mid-Ming dynasty, residents along the coast of China’s Fujian province have been migrating overseas, with some settling in Southeast Asia. Some of those from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in Southern Fujian settled in Malacca and made their fortunes there, paving the way for the subsequent influx of Chinese immigrants to Singapore in the 19th century to engage in commercial activities. In Singapore, the Hokkiens were more extensively involved in various economic activities, compared to other dialect groups.

The Chinese have been flocking to Singapore since the signing of a treaty in 1819 giving the British the right to set up a trading post on the island. The Hokkiens have remained the largest dialect group among the Chinese population. By the second half of the 19th century, the Chinese in Singapore were working in over 110 professions across various trades. In particular, the Hokkiens were involved in sectors including entrepot trade, shipping and lighterage, banking, insurance, remittance, plantations, construction, transportation, culture and entertainment, hairdressing, food and beverage and tea merchanting.

Entrepot trade and commercial activities

Since the founding of modern Singapore in 1819, the growth of its entrepot trade spurred the island’s development, and provided a platform for Hokkien merchants, especially Peranakans who were fluent in English and Malay, to make their mark. By facilitating the entrepot trade, the Hokkiens played an active bridging role, becoming indispensable importers and exporters. They established business networks across Southeast Asia and sourced rubber raw materials from the Malay Peninsula and the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). They processed the rubber locally into sheets and shipped them to Singapore, and distributed them to local businesses through middlemen known as jiubahang (“98% trades”)1 for reselling in Europe and the United States. The Hokkien traders also purchased tropical produce (such as pepper, coffee) and rice from neighbouring regions, gathering these goods in Singapore before selling them to other parts of the world.

For a long time, commercial activities have been the economic mainstay of the Hokkien community, with most Hokkiens working in this sector. These activities mainly comprise wholesale and retail businesses. Wholesalers dealt in a wide range of goods, including rice, local produce (such as dried coconut, pepper, gambier, sago powder) and general merchandise (such as textiles, food and daily necessities). Hokkien-run retail shops were all over Singapore, with the majority being grocery shops and departmental stores. The former sold a variety of goods, mainly sugar, rice, oil, salt and canned food, while the latter dealt in textiles, clothing and footwear.

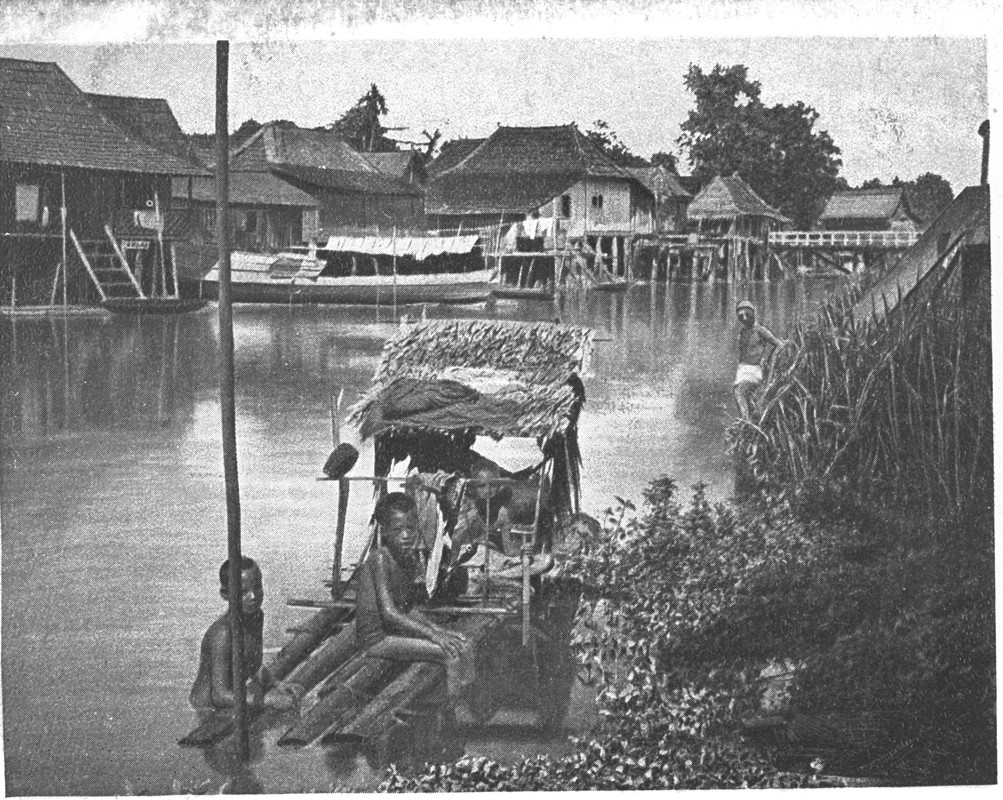

Complementing the commercial trade was the emergence of the shipping and lighterage industry, in which Hokkien merchants played a pivotal role. Among the notable Hokkien merchants in the shipping industry were those from Zhangzhou, Fujian, with Wee Bin (1823–1868) being one of the pioneers. In 1856, he founded Wee Bin & Co., which owned over 20 ships that plied between Singapore, China and the Dutch East Indies. More Hokkiens later joined the shipping trade, including Khoo Tiong Poh (1830–1892), Tan Kim Ching (1829–1892), Tan Keong Saik (1850–1909), Lim Ho Puah (1841–1913) and his son Lim Peng Siang (1872–1944), and Oei Tiong Ham (1866–1924). In Singapore’s barge industry, most of the operators were also Hokkiens from Tong’an, Fujian, followed by the Teochews. For example, Lim Kim Tian (1879–1944), whose ancestral home was in Tong’an, was a well-known barge owner and once served as the president of the Singapore Lighter Owners’ Association.

Banking industry

As trade and commerce activities grew, Chinese merchants had a growing need for robust financial services to facilitate their business dealings. However, Singapore’s banking industry in the 19th century was monopolised by British banks, and language and cultural barriers made it difficult for the Chinese to do business with them. As the Chinese community lacked the financial experience, capital and talent required to run banks, it took them a long time before Chinese-funded banks were established.

It was not until the early 20th century that these banks began to emerge. Early Chinese-funded banks founded by leaders of the Hokkien community included the Chinese Commercial Bank, the Ho Hong Bank, and the Oversea-Chinese Bank. The chairmen and directors of these banks were mainly Hokkien capitalists, including Lim Peng Siang, Lee Kong Chian (1893–1967) and Yap Twee (1897–1984). Today’s Oversea-Chinese Banking Corporation Ltd was formed through the merger of the three abovementioned banks and has since become one of Singapore’s largest Chinese-funded banks. Another Chinese-funded bank, the United Overseas Bank, was founded in 1935 by Wee Kheng Chiang (1890–1978), Ong Piah Teng (1892–1957), and other leaders of the Hokkien business community.

Plantation and tea industries

The earliest Hokkiens to engage in large-scale plantations were Tan Kee Peck (unknown–1909) and Tan Tye (1839–1898), who were respectively the fathers of Tan Kah Kee (1874–1961) and Tan Chor Lam (1884–1971), both prominent figures in Singapore and Malaysia. Tan Kee Peck initially operated a rice mill, and later started a sago factory to produce sago for export. He also branched out into pineapple cultivation. Tan Tye was a timber merchant and pineapple farmer. He set up a pineapple processing plant in the northern bank of Clarke Quay, and shared the nickname “Pineapple King” with Lim Nee Soon (1879–1936), a Teochew who was also involved in pineapple cultivation.

In terms of rubber cultivation, Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957) and Tan Chay Yan (1871–1916, grandson of Tan Tock Seng), whose ancestors hailed from Haicheng, Fujian, were among the earliest pioneers. Tan Kah Kee also began investing in the rubber industry in the 1920s, focusing on diversifying rubber products. Employees of Tan Kah Kee’s companies, including Lee Kong Chian and Tan Lark Sye (1897–1972), were key leaders of the local Hokkien community. In 1919, Hokkien rubber merchants established the Rubber Trade Association of Singapore, with a predominantly Hokkien leadership.

Fujian is a prominent tea-producing region, with tea merchants primarily from Anxi, who had long travelled to Southeast Asia to establish tea businesses to market tea from their hometown. Among them, the earliest to start a tea firm in Singapore was Koh Beng Jin (birth and death years unknown) and his brother, who were from Daping, Anxi. They founded Koh Beng Huat Tea Merchant in 1905. Later, more and more Hokkiens established their own tea companies, the most famous being the Lim Kim Thye Tea Company headed by Lim Keng Lian (1893–1968). These firms imported tea from China, and roasted and packaged it, before distributing it to retailers. In 1928, the Singapore Tea Merchants’ Association was established with 22 members, 15 of whom were from Anxi.

In the early days, apart from their storefront businesses, tea merchants also operated tea vans, which travelled from Singapore to various parts of Malaya selling wholesale tea leaves. Painted with brightly coloured advertisements, these vans moved around cities, towns and villages. Besides the Chinese, other ethnic groups in these places also patronised the tea vans. The tea vans of Pek Sin Choon Pte Ltd, established in 1925, featured an image of a big buffalo to promote its “Cowherd Boy on Buffalo” tea brand. When the van arrived in a small village, the local children would recognise it from a distance and excitedly shout in Hokkien, “The buffalo van is here, the buffalo van is here!” This demonstrates just how deeply ingrained the brand was in the community.

Other trades

In addition to the abovementioned traditional trades, the local Hokkien community have also long been involved in industries such as remittance, construction (fanglang2), transportation, hairdressing and food. In the remittance industry, the Kiaw Thong Exchange set up by Lim Soo Gan (1913–1993), a native of Anxi, Fujian, was a pioneer. In construction, Nan’an native Lim Loh (unknown–1929) and construction magnate Lee Kim Tah (1902–unknown) were notable figures. In transportation, the industry was dominated by the Henghua (Hinghwa) and Futsing (Hockchia), who were involved in services related to horse-drawn carts, rickshaws, tricycles, bicycles, and even bus companies. In hairdressing, the pioneers were mostly Foochow (Hockchew), who established Singapore’s earliest hairdressers’ association, Zheng Ke Xuan, in 1909. In food processing, the local production of soy sauce, canned pineapple and biscuits were also considered traditional trades of the Hokkien community in Singapore. Long-established brands such as Tai Hua Soy Sauce, Lee Pineapple Co Ltd, Khong Guan Biscuit, and Yeo Hiap Seng are all household names in Singapore.

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the economic activities of the Hokkien community continued to grow and diversify. As the largest Chinese dialect group in Singapore, the Hokkien community is also seen to be wealthy and influential, and has long held a significant position in the Chinese business community.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡福建人的传统行业. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Acting as intermediaries between producers and buyers, these firms were responsible for wholesaling local produce on behalf of their clients, charging a commission of typically 2% of the transaction value. This earned them the name jiubahang (literally “ninety-eight firm”). |

| 2 | Originally, fang referred to square timber and lang to a passageway in a building. In Singapore, fanglang has an extended meaning, referring to shops selling building materials such as timber, cement, sand, bricks and small hardware items. |

Lim, Kai Thiong and Tan, Keng Teh et al. Dongnanya de fujian ren [The Hokkien community in Southeast Asia]. Xiamen: Xiamen University Press, 2006. | |

Ng, May Fun. “Xinjiapo fujian ren shequn zhi yanjiu (1945–1965)” [The Hokkien community in Singapore (1945–1965)]. Singapore: MA thesis, Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 2006. | |

Perng, Peck Seng and Tan, Kian Choon et al. Tou lu: Xinjiapo fujian ren de hangye [Headways: The professions of the Singapore Hokkiens]. Singapore: Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, 2008. |