Local lexicon: ‘Bread’ in Nanyang

Western colonisation of the East in the 16th century resulted in an East-West cultural exchange and dialogue. Given the Chinese saying, “Food comes first for the people” (min yi shi wei tian), the differences between their respective food cultures naturally stood out when the Chinese encountered the Westerners. For instance, rice is a staple food for the Chinese, whereas bread is central to the Western diet.

So how did the Chinese community in Nanyang first encounter bread, and how did it go on to become a common food item in their diet? In Nanyang’s multicultural environment, bread was known by different names at different periods. As the terminology developed, its Mandarin name went through stages of likening, borrowing, and forming new words. The term mianbao (面包) finally emerged as the favourite and was added to the Nanyang Mandarin lexicon.

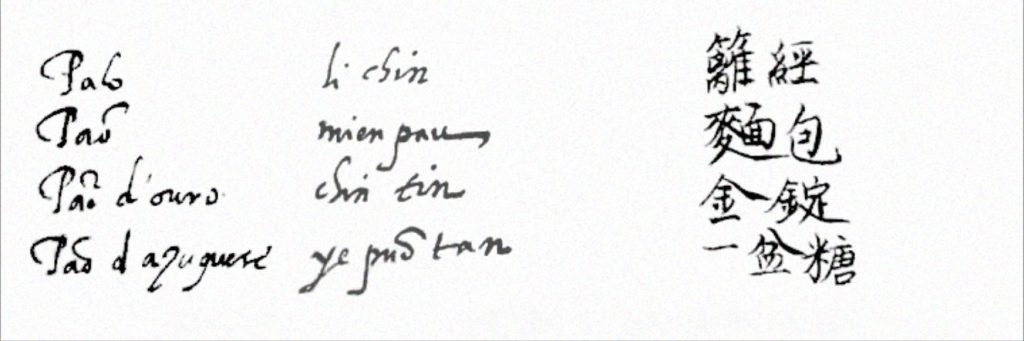

The word ‘pao’ in Dicinario Portugues-Chines

Portugal was the first Western power that colonised territories in Southeast Asia. When the Portuguese occupied Malacca in 1511, Chinese immigrants were already living there. The Portuguese later left behind a Dicinario Portugues-Chines (Portuguese-Chinese dictionary) in Macau, which, according to researchers, was compiled in the 1580s by Portuguese missionaries and the Chinese. Among the Chinese editors, there might have been some who were Chinese Hokkien interpreters from Malacca. The dictionary contained more than 5,600 Chinese words or phrases, and most of them were Nanyang Hokkien words. Among these were three Chinese words or phrases in Mandarin related to bread. They were mianbao (pao in Portuguese; “bread” in English), mianbao pu (forneiro in Portuguese; “bread shop” in English), and mai mianbao de (padeir in Portuguese; “bread-seller” in English). These were the earliest known records of the Chinese word mianbao.

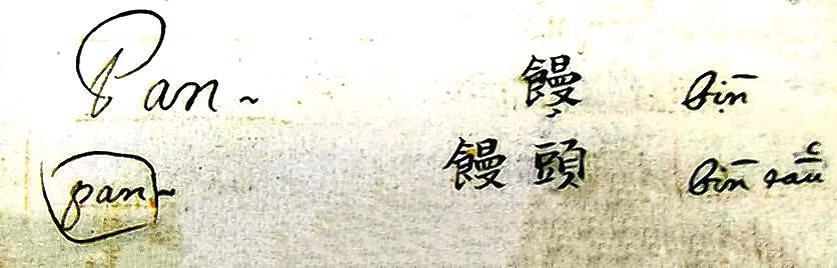

The word ‘pan’ in Dictionario Hispánico Sinicum

When the Spanish arrived in the Philippines in 1541, there was already a big Chinese community living in the country, mostly from Zhangzhou in China’s Fujian province. The Spanish left a manuscript of the Dictionario Hispánico Sinicum (Spanish-Chinese dictionary) behind in the Philippines, which was then compiled into a book in the 1620s by the priests from the Dominican Missionaries together with the Chinese Hokkiens living in the Philippines. The manuscript contained around 2,700 Chinese words and phrases. Most of them were words used in daily life, and the word “bread” was naturally included as it was a staple food of the Spanish. The entry “pan”, Spanish for bread, was glossed in Chinese as man and mantou. The Chinese did not have a food like bread in their culture originally, but mantou (steamed bun), a traditional food of the Chinese, was also made using flour. Using mantou to refer to “bread” allowed the Chinese to understand it easily, without having to create a new word.

The word ‘roti’ in the Dutch Minutes of the Board Meetings of the Chinese Council

The Dutch were the third European colonial power to arrive in Southeast Asia. The Chinese had a long history of going to Indonesia to do business or settle, so the Chinese population in Indonesia was bigger than in other parts of Southeast Asia at that time. Early documentary records that the Chinese left behind in Indonesia included The Chinese Annals of Batavia and Minutes of the Board Meetings of the Chinese Council. These books were precious source material for research on the language of overseas Chinese in the early days. In The Chinese Annals of Batavia, one can find the record of an incident that happened in 1732, when the governor built a water mill in front of his residence so that bakers could pay a fee to use the mill to grind flour.

A judicial inspection record documented in the Minutes of the Board Meetings of the Chinese Council on 8 October 1844 showed that bread was referred to as “roti”, a word derived from Hindi. The Indians called pancakes made with flour “roti”, and when the Europeans took bread to India, Indians used the word “roti” to also refer to bread. When Indian pancakes were taken to the Malay Archipelago by Indian immigrants, the word “roti” was absorbed into the Malay and Indonesian lexicons. It has since become a word for Indian pancakes and bread.

Conforming to local customs, the Indonesian Chinese referred to bread as “roti” as well, which was a natural choice for overseas Chinese living in a multicultural society.

In its early days as a commercial port, Singapore, then a British colony, imported bread from nearby Batavia (Jakarta). On 15 March 1832, the English newspaper The Singapore Chronicle And The Commercial Register published an advertisement for a bakery called John Francis & Son, which could have been among the first batch of bakeries in Singapore. On 15 September 1842, a reader wrote a letter to the editor of The Singapore Free Press about Chinese bakeries. That was an obvious indicator that there were already Chinese-operated bakeries in Singapore during that period.

“mianbao” become a frequently used word

Lat Pau, published from 1887 to 1932, had a large corpus on the term mianbao, proving that it had already become a frequently used word in the newspapers then. Two major Chinese dailies, Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh (both first published in the 1920s), are ideal research material for the local Mandarin lexicon. From their first publications to the time around World War II, both had always used mianbao as their only word of choice for “bread”. This showed that since the early days, mianbao had been accepted as a fixed term in the Mandarin lexicon of the Singapore Chinese community.

Even though Singapore uses the word mianbao in written form, it is still common to use “roti” to refer to bread. The difference between the written and spoken forms of Singapore Mandarin is a reflection of Singapore’s multiculturalism. As the Indians and Malays use the word “roti” to refer to bread, the Chinese and the English-speaking community also adopted it, and “roti” became a common word used across various ethnic groups. “Roti” has endured in the lingo of Chinese Singaporeans because of a strong social basis.

Singapore did not only inherit the legacy of the early Nanyang Mandarin language and adapt it into the Singapore Mandarin lexicon. The migration of Chinese to Southeast Asia, as well as the distribution of Singapore Chinese newspapers in the region, have also made Singapore a centre for Chinese-language communication. The country continues to play an important role in developing and furthering the legacy of Nanyang Mandarin.

This is an edited and translated version of 【本土语汇】面包. Click here to read original piece.

Hsu, Yun Tsiao. Wenxin diaochong [Reflections on language]. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1973. | |

Khoo, Kiak Uei. Malaixiya huayu yanjiu lunji [Collected writings on Malaysia’s Chinese-language studies]. Kuala Lumpur: Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies, 2018. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Lunxue zazhu conggao [Collected writings of Lim Buan Chay]. Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2017. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Yuyan wenzi lunji [Collected writings on language]. Singapore: National University of Singapore’s Department of Chinese Studies, 1996. | |

Lim, Earn Hoe. Wocheng woyu: xinjiapo diwenzhi [Our city, our language: Chronicling Singapore’s Chinese language heritage]. Singapore: Great River Book Co., 2018. | |

Wong, Wai Tik. Shicheng yuwen xiantan [Languages in Singapore]. Singapore: Federal Publications, 1995. |