Local lexicon: The two Chinese terms for ‘week’

The idea of a seven-day week does not feature in the traditional Chinese lunar calendar. The concept was introduced to the Chinese by Western colonisers who arrived in Southeast Asia from the 16th century onwards.

The Chinese in Southeast Asian were the first to use libai (礼拜) to mean “week”. While libai originally referred to Sunday worship, the term was eventually used to refer to the seven-day week. The earliest-known record of such usage appears in the Dictionario Hispánico Sinicum, compiled in the 1620s by Spanish missionaries and Hokkien Chinese in the Philippines. The appendix of this Spanish-Chinese dictionary included the names for the days of the week, each prefixed with the term libai. For example, Sunday was known as libai tian (“day of worship”), and was followed by libai yi (Monday, where yi means one), libai er (Tuesday, where er means two), and so on. This is the first known written evidence that Chinese community using ‘libai’ as a term to refer to time, and the seven-day week.

New vocabulary for new concepts

In the Dictionario Hispánico Sinicum, the entry for libai has two corresponding Spanish terms: “semana” (meaning “week”) and “domingo” (meaning “Sunday”). A note states that the Chinese did not have names for each day of the week, and instead used numbers to refer to them. We can thus infer that the concept of a seven-day week did not exist for the Chinese before this.

The Chinese in Southeast Asia accepted the use of libai to refer to time and the seven-day week more than 200 years before this happened in China. The uniform adoption of new terms and concepts by the Chinese in different parts of Southeast Asia was spurred by the region’s business and immigration networks.

After the British established a trading post in Singapore in 1819, the island rapidly became a hub for regional trade and Chinese immigrants. Due to its geographical location and its majority-Chinese population, Singapore became the main place for the development of Nanyang (Southeast Asian) Mandarin. For example, the term libai and the concept of a seven-day week were already widespread in Singapore by the early 19th century, as seen in Chinese-language documents and correspondence from early Christian churches.

Today, the standard term for “week” in the Chinese language is xingqi (星期), while libai is used in more colloquial contexts. This change is not simply due to the phenomenon of a gradual divergence between spoken and written terms. Rather, it stems from the cultural conflicts that arose as libai spread from Southeast Asia to China.

During the late Qing dynasty, reformists in China pushed for a shift to the Western calendar system, saying that it was scientifically-based, straightforward and practical. However, China’s gentry felt that libai was too strongly associated with Western religion. While they accepted the concept of a seven-day week, they argued that libai should be replaced with a more nationalistic term to prevent the erosion of Chinese culture.

Xingqi becomes mainstream

In the late 1890s, xingqi replaced libai as the term for “week” in China. An existing Chinese term, xingqi (literally “star period”) was repurposed to refer to the seven-day week, as it reflected the Chinese tradition of observing celestial bodies to determine the calendar system. In 1906, when the Qing government declared Sundays as rest days, it took the chance to propose the use of xingqi instead of libai. Due to official propaganda and strong support from the gentry, xingqi gradually replaced libai as the standard term for “week”.

In 1911, when the Republic of China was founded, the government officially announced that the country would adopt the solar calendar in place of the lunar calendar. Nationalism and a desire for cultural autonomy further drove the use of xingqi into the mainstream.

By the late 19th century, the term libai — religious connotations notwithstanding — had long been accepted by the Chinese communities of Southeast Asia. As a British colony following the Western calendar system, Singapore was removed from the ideological battles surrounding the term in China. Its Chinese immigrants also had a relatively weaker sense of Chinese nationalism.

In the 20th century, however, China’s reform movement began to influence Singapore. New modern schools and Chinese-language newspapers were established, and the first stirrings of a nationalist consciousness emerged. When Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925) came to Southeast Asia to enlist support for his revolution, nationalist sentiments surged further. As a result, the ideological battle over libai and xingqi migrated from China to Singapore.

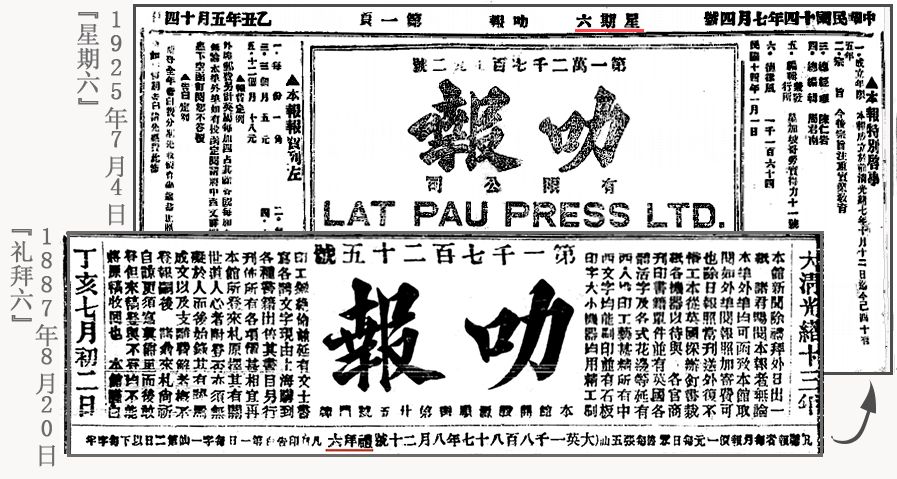

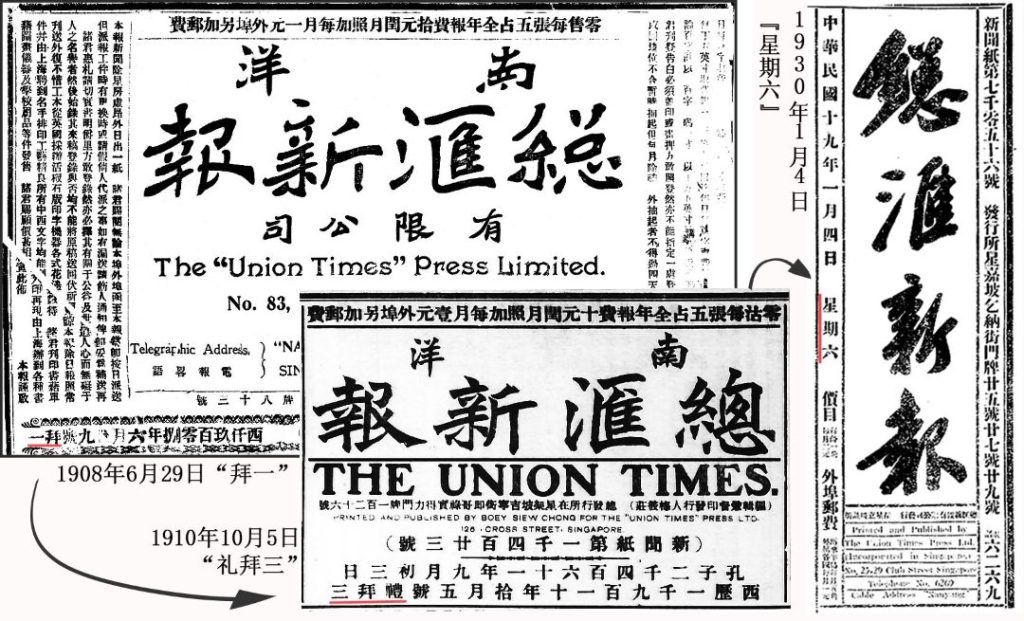

At the time, there were more than 10 Chinese-language newspapers in Singapore. Some were royalist, some reformist, some revolutionary (these tended to have allegiances to the Kuomintang), and some radical. It was easy to identify a newspaper’s political leanings based on whether it used libai or xingqi in its headlines and articles.

Singapore newspapers started using the term xingqi much later than China did, because the Chinese community in Singapore already had its own deep-rooted linguistic habits, and had a weaker nationalist sentiment. The switch to xingqi in Singapore was therefore gradual, even passive. While it reflected elements of China’s modern nationalism, it did not spark cultural conflicts or disputes between the Eastern and Western religious communities. Today, Chinese Singaporeans use xingqi as the standard term for “week”, but when it comes to colloquial usage, libai is still going strong.

This is an edited and translated version of 【本土语汇】“星期”与“礼拜”. Click here to read original piece.

Hsu, Yun Tsiao. Wenxin diaochong [Reflections on language]. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1973. | |

Khoo, Kiak Uei. Malaixiya huayu yanjiu lunji [Collected writings on Malaysia’s Chinese language studies]. Kuala Lumpur: Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies, 2018. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Lunxue zazhu conggao [Collected writings of Lim Buan Chay]. Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2017. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Yuyan wenzi lunji [Collected writings on language]. Singapore: National University of Singapore Department of Chinese Studies, 1996. | |

Lim, Earn Hoe. Wocheng woyu: xinjiapo diwenzhi [Our city, our language: Chronicling Singapore’s Chinese language heritage]. Singapore: Great River Book Co., 2018. | |

Wong, Wai Tik. Shicheng yuwen xiantan [Languages in Singapore]. Singapore: Federal Publications, 1995. |