Singapore’s Chinese film and television industry

For much of the 20th century, Singapore’s film and television industries developed separately and hardly crossed paths. Singapore’s film industry was largely driven by private enterprises, while the television industry was owned by the state or state-owned investment companies. It was not until the mid-1990s that these two major media industries finally converged.

The beginning of local Chinese films

Singapore’s film industry began in 1927 with the silent Chinese film Xin Ke (The New Immigrant). Financed by entrepreneur Low Poey Kim (1902–1959), the film brought together experienced filmmakers from mainland China and Taiwan, who worked with local film enthusiasts to produce the film. Back then, Singapore had no experience in short film production and Xin Ke made history by debuting as a feature film, making it Singapore’s first movie. However, the film did poorly at the box office due to a lack of support from the industry and censorship by the British colonial government. As a result, Low’s filmmaking career came to a halt. From 1927 to 1978, similar problems kept recurring, resulting in only 22 Chinese-language films being produced in Singapore over a span of more than 50 years.1

At that time, the distribution and screening networks for Chinese-language films were mainly centred in Shanghai (1920s–1940s) and Hong Kong (1950s–1990s). This meant that the nascent local Chinese cinema not only lacked industry support, but also faced strong competition from the two cities. Shaw Organisation and Cathay Organisation, which had extensive film distribution and screening networks in post-war Malaya, regarded Singapore as a production hub for Malay films instead. They established the Malay Film Productions and Cathay-Keris Film Productions respectively to produce films targeting Malay-speaking audiences across Southeast Asia. Backed by powerful film distribution and screening networks, these two major Malay film companies were able to continue making films, releasing nearly 300 Malay movies over 25 years in what was known as the golden age of local Malay cinema.

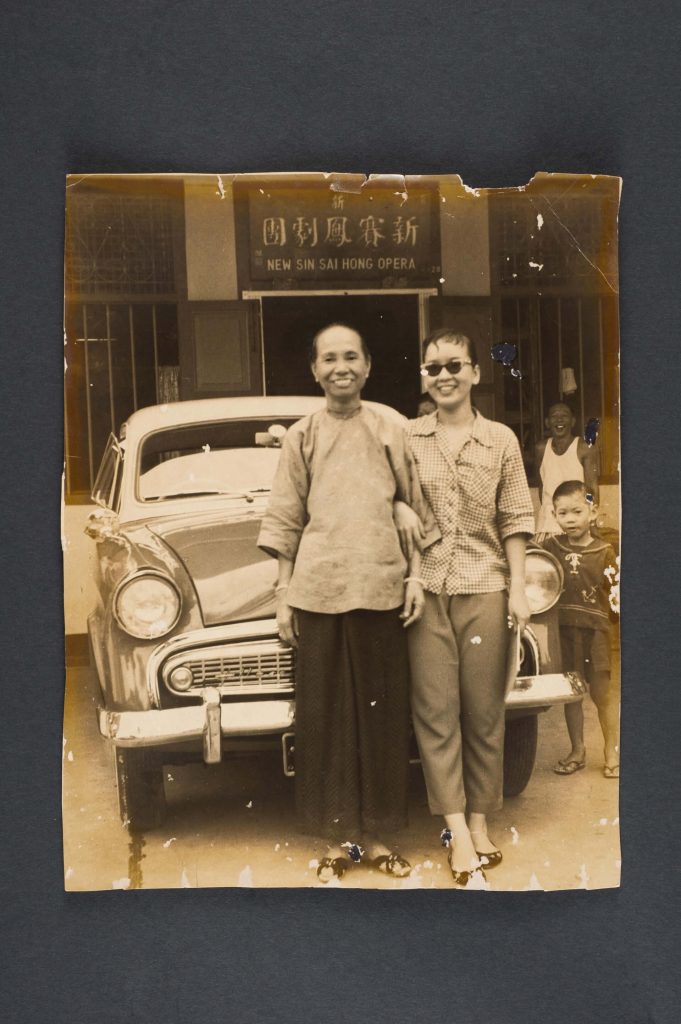

While local Chinese film productions during this period were sporadic, Singapore did not lack cinematic talents. Chng Soot Fong, the queen of Amoy-dialect cinema who made her stage debut as a getai singer, as well as comedy duo Wang Sha and Ye Feng, were scouted by Hong Kong filmmakers for their exceptional talent. They subsequently pursued their careers in Hong Kong and were among the earliest Singaporean movie stars who found success abroad.

Dawn of the SBC era

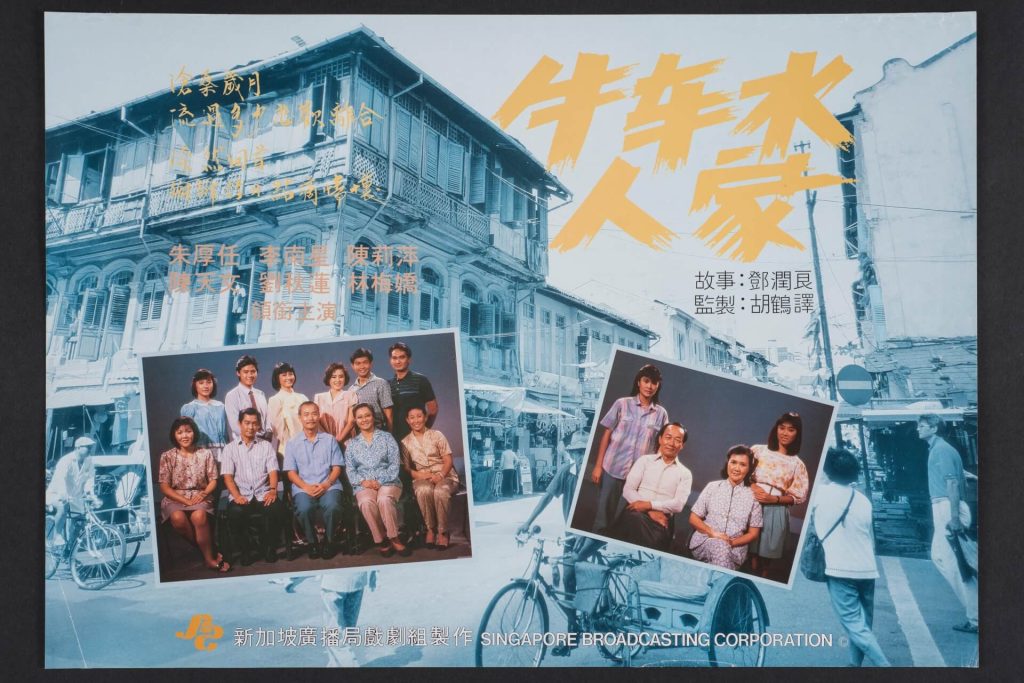

Singapore became the world’s fourth television broadcaster and the first in Southeast Asia to offer Chinese programmes in 1963. From the start, local television was positioned as an important tool in nation-building and tasked with the triple mission of informing, educating and entertaining Singaporeans. During the era of government-run broadcasting, the programmes primarily focused on informing and educating the public, and their entertainment value was relatively low. The Central Production Unit (renamed Current Affairs in 1970) played an exceptionally vital role during this period. Among its Chinese productions, the inter-school debate and inter-varsity debate held in 1968 were well lauded by viewers. As for drama programmes, be they children’s shows or television serials, educational value was prioritised over entertainment, and most of the actors were amateurs. It was only after the government-owned Radio and Television Singapore was restructured into the Singapore Broadcasting Corporation (SBC) that the entertainment value of Chinese programmes and professionalism of actors were enhanced.

During the SBC era, local Chinese dramas and variety shows saw significant improvements in quality and quantity. With help from Hong Kong’s television professionals, Chinese TV serials in the 1980s and 1990s became a source of soft power for Singapore. These productions were not only popular in Chinese-speaking regions, but also dubbed in other languages for distribution in Southeast Asia. The success of Chinese dramas boosted Singapore’s confidence in facing regional competition. In line with the tide of globalisation, the government decided in 1995 to privatise SBC, which remained owned by Singapore government’s investment company Temasek Holdings. By privatising SBC as the Television Corporation of Singapore (TCS), the government hoped it would have greater flexibility to respond to external competition.

Following privatisation, TCS converted Channel 8 into a fully Chinese-language channel and added other new television channels. At the same time, the Economic Development Board (EDB) successfully attracted several foreign satellite television channels to set up regional hubs in Singapore. These new local and foreign channels required locally produced programmes or services, thereby creating growth opportunities for local production houses.

Revival of local cinema

In the late 1980s, Singaporeans’ expectations for local films grew, and discussions on reviving local film production gained momentum.2 In 1989, then-chairman of EDB Philip Yeo pointed out that the film sector could drive Singapore’s economic growth, including creating more job opportunities, increasing business spending and enhancing Singapore’s image as a tourist destination.3 The same year, Ngee Ann Polytechnic set up a School of Film & Media Studies, signalling Singapore’s intention to nurture talent in this field.

In 1991, after a hiatus of more than a decade, Singapore saw the release of Medium Rare, a co-production with Australia. However, the film did not do well at the box office and received poor reviews, causing local feature film production to stall again. The same year, the Singapore International Film Festival, then in its 5th edition, introduced the Silver Screen Awards, a competition segment that included a Singapore Short Film Category. This category had a far-reaching impact on local feature film production. Several winners of the Singapore Short Film award in the 1990s went on to release feature films in the early years of Singapore’s film revival. These auteurs included Eric Khoo, Ong Meng, Kelvin Tong, Lim Suat Yen, Cheah Chee Kong, Wee Li Lin and Jack Neo. Their experience in short film production and networks created opportunities for them to make feature films. For instance, Khoo secured sponsorship from Kodak after his win in 1994 for his short film Pain,4 which enabled him to produce his debut feature film Mee Pok Man (1995).

The confluence of movies and television

Local feature film production was finally restarted in 1995 with Khoo’s Mee Pok Man. Around the same period, some production companies serving television channels also began producing films or participating in film projects. For instance, Oak3 Film, which was established in 1996 and one of Singapore’s earliest production houses, initially produced Malay programmes for TCS, then went on to release the Chinese film The Road Less Travelled in 1997. Meanwhile, television actors also began venturing into movies. Jack Neo, Mark Lee, Henry Thia, Patricia Mok and John Cheng (1961–2013), who became household names through their performances on Channel 8’s variety show Comedy Night, went on to star in Money No Enough and The Return of Liang Po Po. Both films grossed S$5.8 million and S$3.03 million respectively, becoming the top-grossing films in Singapore in 1998 and 1999. In 1998, TCS established a subsidiary Raintree Pictures specifically for film production, which further bridged the gap between Singapore’s television and film industries. From 1998 to 2012, Raintree Pictures produced 37 films, over half of which were local or co-produced Chinese films.5

The flow of talent between television and film has exerted a positive impact on the overall development of Singapore’s film and television industry, allowing Chinese movies to be produced year after year since 1995. Local film output surpassed the annual threshold of 10 films in 2005, and peaked at 32 films in 2008. Of the films produced annually, a third to half were Chinese films. While some film studios could not sustain their business after making just one movie during this period, the broader environment where the film and television industries complemented each other, coupled with support from the Singapore Film Commission set up by the government in 1998 and the involvement of local film distributors in production, have enabled local Chinese cinema to finally break the curse of unsustainable production in the early years.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡的华语影视产业. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | |

| 2 | “Bendi yingyi gongzuozhe xin zhanwang” [New prospects for local film professionals], Shin Min Daily News, 20 March 1987; “Zhengfu youyi kaituo bendi dianying shichang” [The government aims to open up the local film market], Lianhe Zaobao, 10 May 1987; “Ruhe fazhan xinjiapo dianyingye? He linguo hezuo ke kaiban kecheng” [Collaboration with neighbouring countries and introduction of courses are key to developing Singapore’s film industry], Shin Min Daily News, 23 February 1987; “Yule wangguo dai you ri” [Could Singapore become an entertainment hub?], Lianhe Zaobao, 6 August 1989. |

| 3 | “Yang Lieguo zhichu, fazhan woguo dianyingye ke cujin jingji chengzhang” [Philip Yeo: Film sector is key to our economic growth], Lianhe Zaobao, 9 March 1989. |

| 4 | Dion Tang, “Rensheng ru xi dianying bushi meng” [Eric Khoo and Anthony Chen: crafting passion on screen], ICON, 7 June 2024. |

| 5 | See “MediaCorp Raintree Pictures,” Singapore Infopedia. |

“MediaCorp Raintree Pictures.” Singapore Infopedia. | |

Tang, Dion. “Rensheng ru xi dianying bushi meng” [Eric Khoo and Anthony Chen: crafting passion on screen]. ICON, 7 June 2024. | |

Tay, Philip J., Choo Lian Liang, et al., eds. Huiwang jialigu shan [Reflections from Caldecott Hill]. Singapore: Global Publishing, 2021. |