From Singapore Performing Arts School to The Theatre Practice

The Theatre Practice is an important bilingual theatre group in Singapore. Its predecessor, the Singapore Performing Arts School, was founded by the playwright Kuo Pao Kun (1939–2002) and dancer Goh Lay Kuan, both recipients of the Singapore Cultural Medallion Award.

In 1965, with the experience they had gained from their training in Australia, Kuo and Goh returned to Singapore to establish the Singapore Performing Arts School. From the outset, the school emphasised the importance of both training and practice. As part of training, it offered systematic professional drama and humanities courses, while it continuously experimented with new playwriting and theatrical forms in its practice.

The Performing Arts School’s first theatrical performance was The Test in 1966, which commentators believe marked a significant change in stage design and lighting in theatre. Departing from the traditional method of changing props for each scene, the play introduced the use of lighting to depict space and highlight characterisation, providing audiences with a novel theatre experience. Subsequent performances such as Life Breaks, Dark Souls, and Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle continued to explore forms distinct from traditional realism by combining realistic and impressionistic stage sets and lighting designs.

In 1967, the Performing Arts School started its first drama training course. It ran for over 20 sessions until its discontinuation in 1984, and nurtured numerous talents in the field of theatre. In 1968, the Performing Arts School presented its collective work Hey! Wake Up, which incorporated the theatrical techniques of German playwright Bertolt Brecht (1898–1956) into its portrayal of local social issues and characters. This production once again showcased the school’s ongoing experimentation with theatrical forms.

Later, in 1972, students from the drama class established the independent Selatan Arts Ensemble (renamed Southern Arts Society in 1976), which became one of the most active theatre groups in the first half of the 1970s.

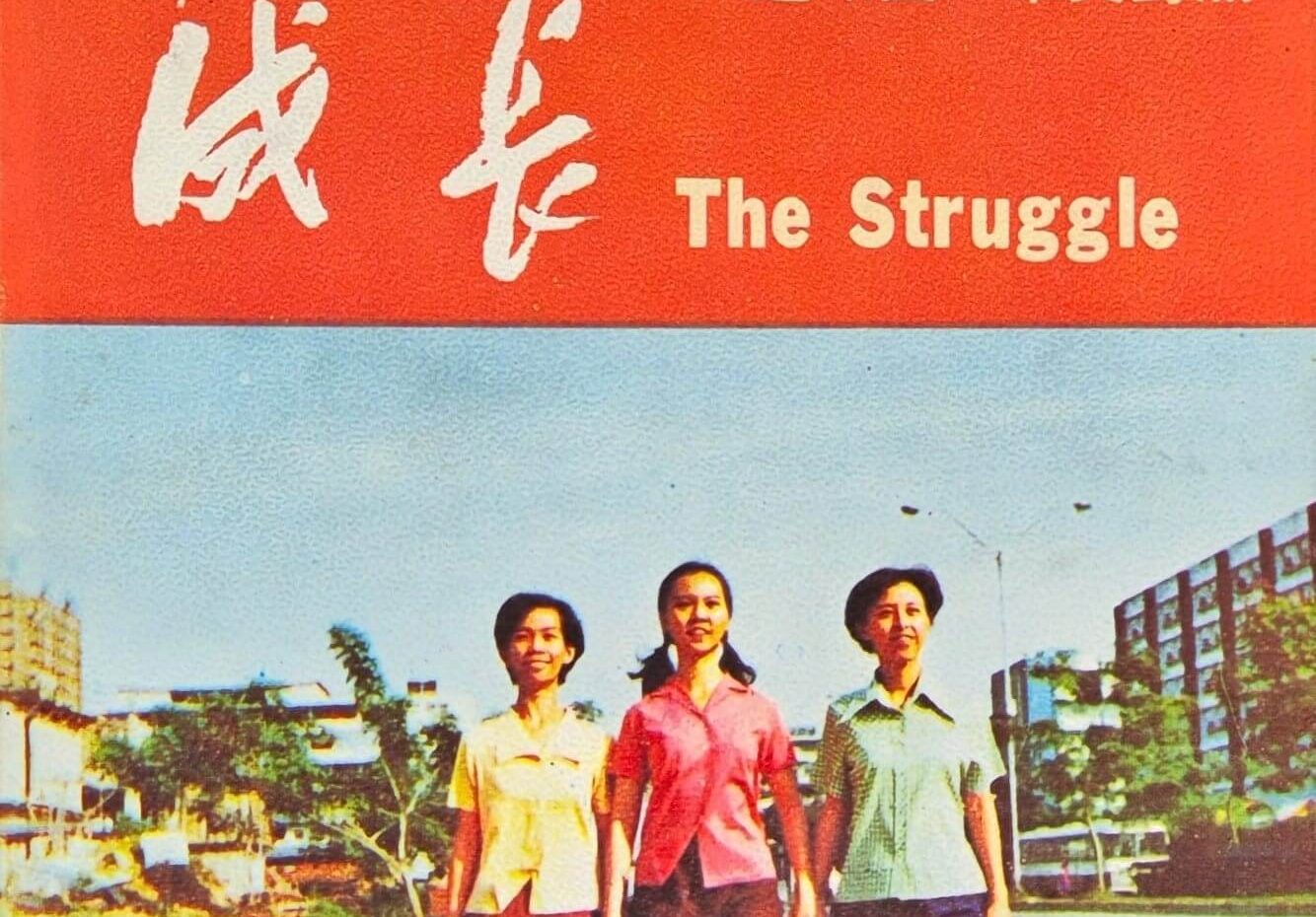

From the latter half of the 1960s, many individual theatre groups began exhibiting a strong leftist orientation, shining light on the concept of class struggle and articulating their ideals for society. The Performing Arts School was no exception, and became one of the groups most frequently subjected to performance bans during this period. The school’s collective creations, Struggle in 1969 and Sparks of Youth in 1971, were both denied performance permits and could not be staged.

In order to avoid the situation in which multi-act plays could not be performed once they were banned, the Performing Arts School adopted an integrated performance approach since 1969. For instance, they introduced “Arts Night”, which featured a combination of short plays, poetry, dance, singing, and other programmes. In addition to public performances, the school also organised various internal “learning and observation nights” to maintain its vitality.

Kuo Pao Kun’s translated dramas

Early Singapore theatre productions featured scripts not only from Chinese works of the May Fourth period but also from European realist classics (particularly those of Russian origin). Theatre groups typically used translations from China for the latter.

Kuo took a different approach. Instead of using Chinese translations wholesale, he either further adapted them or personally translated the English originals. Three plays from the 1940s and 1950s, The Test, Dark Souls, and Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle, were all translated by Kuo and imbued with a strong modern consciousness and the spirit of class struggle.

In 1973, the Singapore Performing Arts School was renamed Practice Theatre School and then Practice Performing Arts School in 1984. In 1986, Practice Theatre Ensemble was established. In 1988, the Practice Performing Arts Centre. was officially registered, relocating to Stamford Arts Centre and operating in parallel with two core entities, Practice Performing Arts School and Practice Theatre Ensemble.

The flourishing of Chinese-language theatre after the 1980s

In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Singapore’s society and economy entered a period of stable development, spurring initiatives to actively kickstart cultural and artistic planning. Coupled with the gradual easing of global Cold War tensions, this provided favourable conditions for cross-national and cross-regional cultural and artistic exchanges. During this period, while serving as a key intermediary and promoter in the local Chinese theatre scene, Kuo also played a crucial role in the realm of theatrical arts and the broader cultural and intellectual spheres. Scholars have even dubbed this 20-year period the “Kuo Pao Kun Era”.

In 1976, Kuo was arrested under Internal Security Act for alleged communist activities and detained for four years and seven months. During this period, Practice Performing Arts School was led by Goh. In 1982, following his release, Kuo participated in the direction and production of his first original work Little White Boat, which premiered at the arts festival sponsored by the Ministry of Culture. Little White Boat was jointly performed by 14 Chinese theatre groups, leading to the resurgence of local Chinese-language theatre, which had largely been dormant in the late 1970s.

In 1984, Kuo began directing bilingual plays with his work The Coffin is Too Big for the Hole. In 1988, he led a group of actors with diverse linguistic backgrounds to create the multilingual theatre production Mama Looking for Her Cat, which featured languages familiar to Singaporeans such as English, Malay, Mandarin, Tamil, Hokkien, Cantonese, and Teochew. Kuo was widely regarded as a representative figure in cross-cultural communication and exchange. While Mama Looking for Her Cat may not have been the first instance of multiple languages being showcased simultaneously in Singapore theatre, it was the first collaborative effort among theatre practitioners from different linguistic backgrounds to create a uniquely Singaporean style of drama.

Besides the Performing Arts School and Practice Theatre Ensemble, other artistic groups and institutions founded by Kuo include The Substation (1990) and the Theatre Training & Research Programme (2000, co-founded with Thirunalan Sasitharan, now known as Intercultural Theatre Institute). He received numerous awards as well, such as the Singapore Cultural Medallion (1989), the ASEAN Cultural Award (1993), the Knight of the Order of Arts and Letters of France (1996), and the Singapore Excellence Award (2002). Goh also received the Singapore Cultural Medallion Award in 1995.

The birth of The Theatre Practice

In 1996, with the aim of promoting traditional puppet theatre to the younger generation, Practice Performing Arts Centre established The Finger Players, which became an independent theatre company in 1999.g

More significantly, in 1997, Practice Theatre Ensemble changed its name to The Theatre Practice. Following Kuo Pao Kun’s death in 2002, Wu Xi and Kuo Jian Hong assumed the roles of Co-Artistic Directors. In 2006, Kuo Jian Hong became the sole Artistic Director. Upholding the spirit of “playfulness” while still rooting its productions in original texts, The Theatre Practice continues to explore more experimental artistic forms today.

In 2005, The Theatre Practice presented the musical adaptation of Kuo Pao Kun’s original script Lao Jiu, marking a significant milestone in the production of Chinese-language musicals by The Theatre Practice. It continues to deepen the connections between local theatre and the world and actively nurture artistic talents in Singapore through various programmes such as the Chinese Theatre Festival (2011–2017), Singapore Theatre Festival (2018–2021), Practice Laboratory (2013), Artist Farm (2017–2020), and the Practice Artists Scheme (2018–present).

In 2016, The Theatre Practice relocated to a double-storey building consisting of three connected units in Waterloo Street, with a multi-purpose black box theatre attached to its clubhouse. The following year, it established a café and art space called Practice Tuckshop on the ground floor of its clubhouse to strengthen its connection with the local community. This was also in line with The Theatre Practice’s focus on sustainable development, which directly influenced its production model. Combining dining experiences with storytelling exchanges, Recess Time (2017–present) is one of the most well-known works by Practice Tuckshop.

To emphasise the importance of arts education, The Theatre Practice continues to offer children’s courses through the Practice Education Project and develop youth theatre productions suitable for different age groups, including the Nursery Rhymes Project (2017–present). These initiatives aim to bring the arts into homes, schools, and communities, making it an integral part of everyday life for Singaporeans.

In 2020, the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic significantly disrupted live performances. As a result, The Theatre Practice set up an online platform that combined video screenings, live streaming performances, and interactive activities to provide audiences with a unique digital theatre experience. It also collaborated with digital technology companies to jointly develop a live streaming system called XIMI.

Today, The Theatre Practice remains one of the most prominent groups in the local theatre scene.

This is an edited and translated version of 从新加坡表演艺术学院到实践剧场. Click here to read original piece.

Practice Theatre School. Dance Potpurri. Singapore: Practice Theatre School, 1979. | |

Quah, Sy Ren. Xiju bainian: Xinjiapo huawen xiju 1913–2013 [Scenes: a hundred years of Singapore Chinese language theatre 1913–2013]. Singapore: Drama Box, National Museum of Singapore, 2013. |