A brief history of Nanyang University

The immigrants from China who arrived in Singapore valued education and the passing down of culture and values. Under British rule from the early 19th century to the mid-20th century, education for the Chinese in Singapore was very much a community effort. Due to limited resources, there were many challenges.

After World War II, the British colonial authorities implemented certain measures that further hampered Chinese-language education in Singapore. First, the 1947 Ten-Year Programme for education planning concentrated all resources on developing English-language education, resulting in an existential threat to the Chinese-language education. Second, following the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the colonial government banned students from Singapore and Malaya from pursuing tertiary education in China to prevent the spread of communist influence. As a result, students from Chinese-medium schools had no avenue for furthering their studies.

These circumstances left the Chinese community in Singapore and Malaya deeply concerned over the future of Chinese-language education. They aspired to come together and establish a university that could forge a complete pathway for Chinese-language education.

The founding of Nanyang University

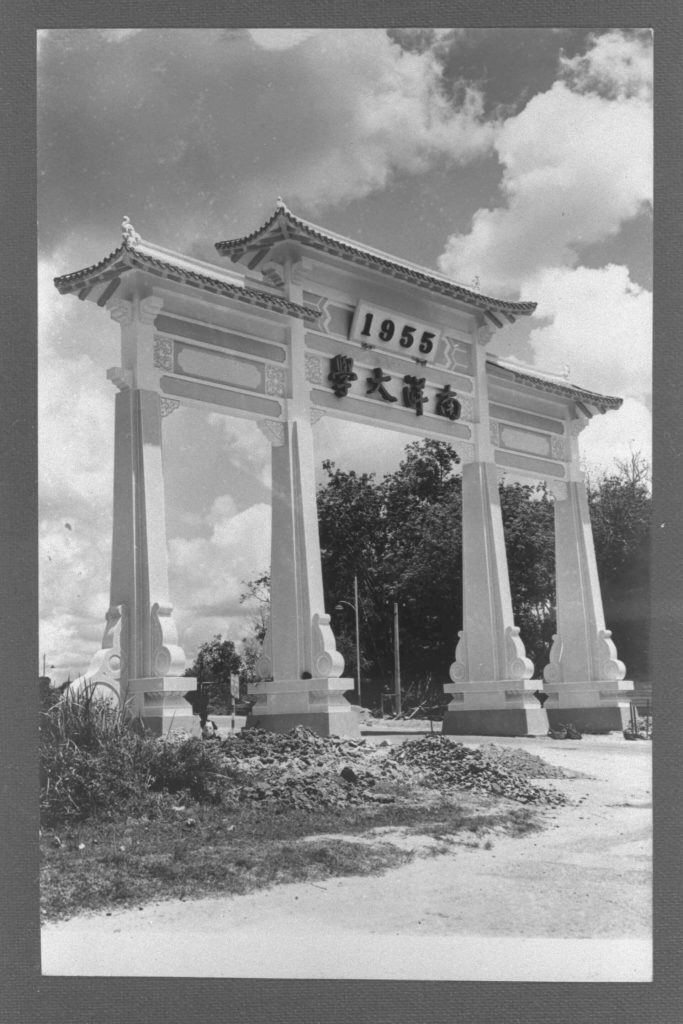

In the 1950s, a few Chinese community leaders called for Singapore to set up a Chinese-language university. Among them, the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan, led by Tan Lark Sye (1887–1972), was a key champion for this cause. In 1953, Tan donated $5 million for the project, and the Singapore Hokkien Huay Kuan donated a 523-acre rubber plantation plot in Jurong as the site of the new university.

This initiative was warmly welcomed by the Chinese community in Singapore and Malaya, and prominent community figures showed their support and joined fundraising efforts. They included Singapore Chinese Chamber of Commerce’s then-president Tan Siak Kew (1903–1977) and then-vice president Ko Teck Kin (1911–1966), Lim Lean Teng (1870–1963), Lien Ying Chow (1906–2004), Ng Aik Huan (1908–1985), Lee Kong Chian (1893–1967), Aw Boon Haw (1883–1954), Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957), Tan Chin Tuan (1908–2005), Lee Choon Seng (1888–1966), Tan Eng Joo (1919–2011), Loke Wan Tho (1915–1964) and Run Run Shaw (1907–2014).

Tan Cheng Lock (1883–1960), founding president of the Malayan Chinese Association, played a unique and crucial role. The English-educated businessman supported Tan Lark Sye and others in communicating with the British colonial authorities, helping to pave the way for the new university.

The construction and operational costs for this university were enormous. The colonial government had no intention of contributing any funding. So from 1953, the preparatory committee started fundraising in Singapore, the Malay Peninsula, Sarawak, North Borneo (a British protectorate), and Indonesia. Chew Wee Kai, a Singaporean researcher of culture and history, wrote: “The Chinese community in Singapore and Malaya swiftly harnessed the strong ground-up support for Nanyang University. The preparatory committee led an unprecedented mobilisation of the community, and donations poured in. People from all walks of life used different ways to give what they could and pool their resources. This spirit was sustained for two, three years.”1

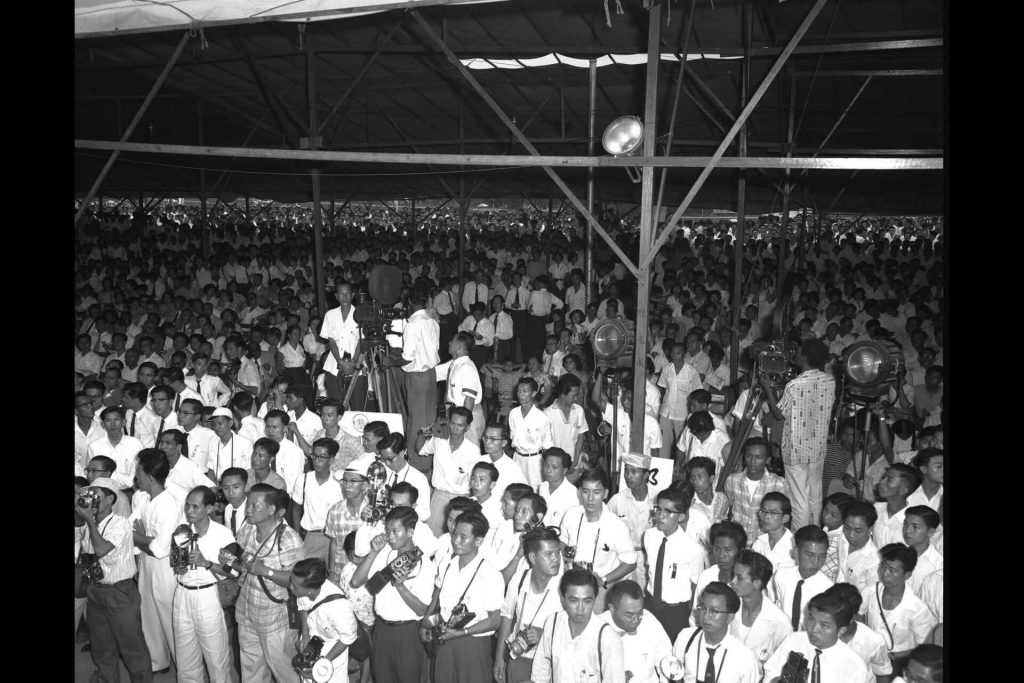

According to Nanyang University’s records, the companies and organisations in Singapore and the Malay Peninsula that took part in these fundraising efforts included around 800 Chinese-owned enterprises; over 300 clan associations; over 300 trade associations, trade unions, and fraternal organisations; around 100 Chinese-medium schools; as well as Chinese temples and cultural groups, which included entertainment organisations, student groups and groups affiliated with clan associations and sports organisations. They staged a wide variety of performances (from concerts to lion dance), carnivals, and sports events to raise funds.2

Grassroots support in Singapore and Malaya was strong, with people from all trades eager to do their part. The ground-up fundraising activities were widely reported in the media, and included charity performances by singers and actors; charity dances by dance hostesses; charity rides from taxi drivers, trishaw pullers and freighters; and charity meals from hawkers. Rallying together to realise the dream, the community found strength in unity.

The preparatory committee led by Tan Lark Sye decided on the name Nanyang University (also referred to as Nantah). “Nanyang” was a common name for Southeast Asia. The name suggested that this would be a university rooted in this region, and serve the community here. During this period, prominent businessman Lien Ying Chow helped to secure Chinese scholar Lin Yutang (1895–1976) as the university’s first chancellor. Lin assumed the post in October 1954. However, his differences with the university’s founders over its ideology and management saw him leaving in March 1955, before classes commenced.

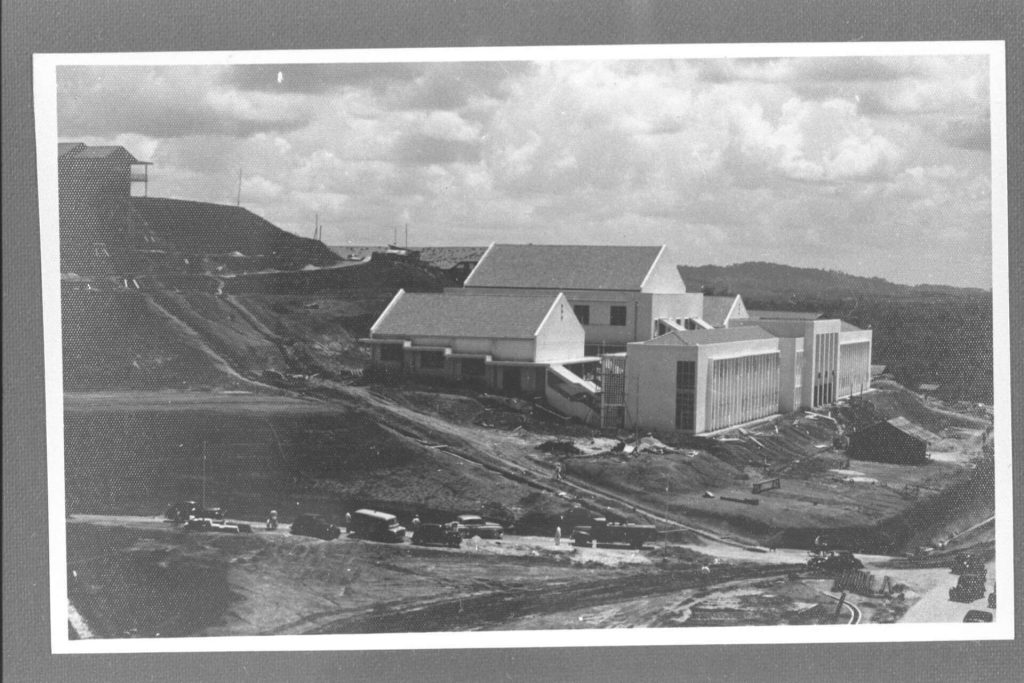

On 15 March 1956, after three years of hard work, Nantah finally welcomed its first cohort of 584 students. That year, the Nanyang University Executive Council was established. It was chaired by scholar Chang Tien Tze (birth and death years unknown) who, as the Dean of Nanyang University, temporarily took on the duties of the chancellor.

In its first year, Nanyang University set up faculties for the arts, sciences and commerce. Departments under these faculties included Chinese language and literature, modern language and literature, history and geography, economics and politics, education, mathematics, physics, chemistry, biology, business administration, and accounting and banking. The university articulated its mission as follows: (1) provide middle-school graduates with opportunities for higher education; (2) train teachers for middle schools; (3) develop talents for Singapore; and (4) meet the needs of an expanding population and developing economy.

On 30 March 1958, Nantah held a ceremony to mark the completion of its first phase of university building. It was attended by tens of thousands of people, with cars and crowds thronging the streets from Jurong’s Yunnan Garden all the way to Newton Circus in town. It was a sight to behold. The guest of honour was then-Governor of Singapore, Sir William Allmond Codrington Goode (1907–1986), who unveiled a tablet commemorating the university’s founding.

Development and reform

Although it had support from the Chinese community, Nantah encountered many challenges and obstacles. The Cold War was in its early stages then, and anti-communist sentiment and racial tensions affected the development of Chinese-language education in the region. Non-Chinese communities that opposed Nantah’s establishment felt that such an institution would damage racial harmony and could further sinicise Malaya. The British colonial government was not keen on it either, as it feared that Nantah would become a hotbed for breeding communists.

After attaining self-governance in 1959, Singapore separated from Malaysia in 1965 and gained independence. During this period, student movements were rife in Nantah. Students staged demonstrations and strikes to protest the government’s interference in university administration and its non-recognition of Nantah degrees. The government was also concerned about the infiltration of left-leaning influences on campus. In this atmosphere of intense conflict, the government (first led by the Labour Front, and subsequently by the People’s Action Party) appointed experts to propose reforms for the university. The resulting recommendations were submitted in three separate reports.

In February 1959, then-Chief Minister Lim Yew Hock (1914–1984) appointed S. L. Prescott (1910–1978), vice-chancellor of the University of Western Australia, to lead a four-member commission in preparing a report on Nantah’s organisation, administration, curriculum, facilities, as well as the calibre of its teachers. The commission was tasked to offer recommendations for reform, which were laid out in the Prescott Report.

That July, newly elected Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew (1923–2015) set up a committee, led by Gwee Ah Leng (1920–2006), then acting medical superintendent of the Singapore General Hospital, to review the Prescott Report. In February 1960, this committee issued its own report, known as the Gwee Ah Leng Report. It recommended that Nanyang University recruit students from other language streams as well, increase its proportion of English-language teaching and start offering Malay-language classes.

In January 1965, the government appointed scholar Wang Gungwu to lead a committee to review Nantah’s curriculum. In September that year, the committee released the Report of the Nanyang University Curriculum Review Committee (also known as the Wang Gungwu Report), which recommended that Nantah replace its four-year undergraduate system with a three-year system (much like the system used in England), and introduce honours degrees. Other recommendations included improving teacher’s qualifications and students’ standard of English, and setting up a Malay Studies department.3

The Chinese community and Nantah students generally disagreed with these recommendations. They worried that implementing the suggested reforms would dilute the institution’s core identity as a Chinese-language university.

In the institution’s early years, Nanyang University’s executive council worked hard to secure government financial support and its recognition of Nantah degrees. The government, on the other hand, hoped for the university to revise its direction and organisation, and ultimately integrate into the national education system. After many years of negotiations, both parties reached a consensus in April 1964. In their joint statement, a key point was stated: Once Nanyang University had shown satisfactory improvement, the Singapore government would accord it the same treatment as the University of Singapore (SU), and help to lighten the financial burden of its students and improve its teacher benefits and facilities.4

As a new school year began in 1966, recommendations from the Wang Gungwu Report were adopted. These included a conversion to a system where three years of study culminated in an ordinary degree, and the introduction of honours degrees. A language centre was set up to help students learn non-Chinese languages. Two years later, Nantah completed its reorganisation. In May 1968, then-Minister for Education Ong Pang Boon announced at the university’s ninth graduation ceremony that the government would formally recognise its degrees.

In March 1970, Nanyang University set up a research institute, with specialisations in Asian studies, business studies, mathematics and natural sciences. Classes started in May that year. In 1972, the Lee Kong Chian Museum of Asian Culture opened. It was funded by collectors, artists, architects, and the Lee Foundation.5

From 1969 to 1972, Nantah was led by chancellor Rayson Huang (1920–2015), a scholar of sciences. He worked hard to expand research facilities (for students pursuing master’s degrees and doctorates), and improve the university’s academic standing. From the academic years of 1975 to 1976, Nantah began to recruit non-Chinese students. It also revamped its curriculum to introduce more flexibility and provide a more broad-based education. This replaced the former approach of instruction that was mainly focused on a single academic discipline. New departments were also established, including computer science, physics and chemical sciences, environmental science, banking and finance, mass communication, sociology, and psychology.

In the 1970s, English-language education became mainstream in Singapore, and the number of students in Chinese-medium schools began to dwindle, resulting in a shrinking recruitment pool for Nanyang University. This became a pressing problem.

On 14 March 1975, then-Minister for Education Lee Chiaw Meng (1937–2001) became the chancellor of Nanyang University. Another extensive round of reforms followed. With the exception of Chinese language and Chinese history, all other classes were now taught in English. In February 1978, when then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew spoke at a lecture organised by Nantah’s Historical Society, he stressed the importance of mastering bilingualism and said: “The Nanyang University campus was an established Chinese-speaking environment. The usage of English could not be easily established in this environment.” He suggested that Nantah students immerse themselves in English-speaking environments.

On 4 March 1978, the councils of Nantah and the University of Singapore issued a joint statement announcing that the latter’s Bukit Timah campus would become the joint campus for classes that were offered to students at both universities. This would allow Nantah students to learn in an English-speaking environment.

From December 1979 to March 1980, then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew engaged in many discussions with Nanyang University’s executive council, which was led by banker Wee Cho Yaw (1929–2024). The subject was the future of the institution. On 7 March 1980, Lee wrote a letter to the council, stating that since 1975, fewer and fewer Chinese-stream secondary school graduates had been applying to Nantah as their first choice for tertiary education. The university also found it hard to recruit new teaching staff with deep expertise. Under these circumstances, he said, “the correct answer … is to merge SU and NU into a National University of Singapore”.

Lee recommended that the Nantah campus be developed into a technological institute, which could serve as the engineering arm of the merged university. The goal: by 1992, when the graduates from this institute were comparable in calibre with American university graduates, it could become a full-fledged university.

The Nantah council accepted the recommendation. On 5 April 1980, Nanyang University officially merged with the University of Singapore. On 8 August 1980, this new entity was launched as the National University of Singapore.

In 1991, Nanyang Technological Institute became Nanyang Technological University (NTU), one year ahead of schedule.

Nantah alumni

In its 25 years, Nanyang University produced 21 cohorts of graduates, educating a total of 12,000 students from Singapore, Malaysia, Southeast Asia and beyond.

Among its alumni is the academic Leo Suryadinata, who once noted that Chinese-medium schools were strong in mathematics, physics, chemistry and biology, and that Nantah nurtured many talents in these areas. Several of them became prominent scholars: Teh Hoon Heng, Chew Kim Lin and Lee Peng Yee from the Department of Mathematics; Hew Choy Sin and Liew Choong Chin from the Department of Biology; and Hew Choy Leong from the Department of Chemistry. Many graduates from the Department of Physics went abroad to further their studies, then returned to their alma mater to develop its computing capabilities. They included Hsu Loke Soo, Chan Sing Chai, Tan Kok-Phuang and Thio Hoe-Tong. Nantah was the first university in Southeast Asia to set up a computer centre. Tan Lip-Bu, who graduated from its Department of Physics in 1978, is a leading figure in the global semiconductor industry. In 2025, he was appointed chief executive of Intel, an American multinational technology company.6

In the humanities, Nantah alumni include Liaw Yock Fang, an internationally acknowledged expert in Malay language and literature; and Yen Ching-hwang, a renowned academic of overseas Chinese studies. Beyond the world of academics, Nantah alumni have also excelled in regional politics, education, finance, business, social services and philanthropy.7 For example, the following Nantah alumni are recipients of Singapore’s Cultural Medallion: authors Wong Meng Voon, Tham Yew Chin (You Jin) and Chew Kok Chang (Zhou Can); calligrapher Tan Siah Kwee; and artist Tan Swie Hian. In the area of religion, John Chew Hiang Chea, the eighth Bishop of Singapore under the Anglican Diocese of Singapore, is also an alumnus.

The Nantah spirit

The Nantah spirit has endured through the decades. Speaking at NTU’s 50th anniversary celebration on 29 August 2005, then-Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong said: “The Nantah spirit remains as relevant as ever. We should keep its flame alive, and nurture a strong sense of community and mutual support, not just in NTU, but also in our other local universities NUS and SMU,8 and indeed in our society at large.”

Today, the Nantah created by the Chinese community in Singapore and Malaya has become a part of history. But the Nantah spirit lives on in the hearts of Singapore’s Chinese community.

List of chancellors and their tenures

- Lin Yutang (1954–1955)

- Chang Tien Tze (1956–1959) (Chairman of the Nanyang University Executive Council)

- Chuang Chu Lin (1960–1964) (Vice-chancellor)9

- Huang Yingrong (1965–1969) (Vice-chancellor cum acting chancellor)

- Lu Yao (1968–1977) (Vice-chancellor [administrative])

- Rayson Huang (1969–1972)

- Hsueh Shou Sheng (1972–1975)

- Lee Chiaw Meng (1975–1976)

- Wu Teh Yao (1976–1977) (Acting Chancellor)10

This is an edited and translated version of 南洋大学历史事略. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Chew Wee Kai, “Cheng changfeng yiju gong xingxue: 1953–1955 nian nanyang daxue mukuan biji” [Notes on the Nanyang University fundraising campaign, 1953–1955], Yihe shiji, 2015, 37. |

| 2 | Chew Wee Kai, “Cheng changfeng yiju gong xingxue: 1953–1955 nian nanyang daxue mukuan biji” [Notes on the Nanyang University fundraising campaign, 1953–1955], 36–48. |

| 3 | On 20 January 1965, the Interim Nanyang University Executive Council appointed a Curriculum Review Committee to conduct a comprehensive review of necessary reforms for all faculties, citing the need to adapt to new requirements. This committee was led by Wang Gungwu, the head of the history department at the University of Malaya; Koh Seow Tee, a lecturer at the Singapore Polytechnic; Lim Ho Hup, the managing director of the Economic Development Board; Liu Kung-Kwei, the acting dean of commerce at Nanyang University; Lu Yao, the chief inspector of schools at the Ministry of Education; Thong Saw Pak, the head of the physics department at the University of Malaya; and Wang Shu-Min, a visiting professor at the University of Singapore. See Report of The Nanyang University Curriculum Review Committee (Singapore: Nanyang University, 1965). |

| 4 | Nanyang University 25th Anniversary Commemorative Magazine, 25. |

| 5 | The collection is now part of the NUS Museum. See Ng Siang Ping, “Cong zengli kan yishu shoucang” [Collecting art through gifts], Lianhe Zaobao, 1 March 2024. |

| 6 | Leo Suryadinata, “Nanda yu qi xiaoyou dui xinma de gongxian” [The contributions of Nantah and its alumni to Singapore and Malaysia], Lianhe Zaobao, 23 September 2016. |

| 7 | Leo Suryadinata, “Nanda yu qi xiaoyou dui xinma de gongxian” [The contributions of Nantah and its alumni to Singapore and Malaysia]. |

| 8 | SMU refers to Singapore Management University, Singapore’s third university founded in 2000. Speech extract from Lee Hsien Loong, “Speech at the NTU 50th Anniversary Celebration,” Ministry of Information, Communications and the Arts, 29 August 2005. |

| 9 | The position of vice-chancellor is equivalent to that of a president in the American university system. Chuang Chu Lin was appointed vice-chancellor in 1960 and was responsible for the management of the university. He tendered his resignation on 1 July 1964. On 8 July, the Interim Nanyang University Executive Council was formed to oversee university affairs, with Liu Kung-Kwei as its chairman. See Nanyang University 25th Anniversary Commemorative Magazine, 9; Nanyang daxue shiliao huibian [The history of Nanyang University], 6–9. According to the 1977 Report on the Standardisation of Chinese Translations of Names of Govt. Departments and Statutory Bodies, “vice-chancellor” was standardised as xiaozhang (meaning principal) in Chinese. |

| 10 | The chancellor position was left vacant from 15 August 1977, with a Special Committee responsible for managing the university’s administration. Tan Chok Kian served as director-general, implementing the committee’s decisions. |

Nanyang University 25th Anniversary Commemorative Magazine. Kuala Lumpur: Nanyang University Alumni Association of Malaya, 1982. | |

Chew, Wee Kai. “Cheng changfeng yiju gong xingxue: 1953–1955 nian nanyang daxue mukuan biji” [Notes on the Nanyang University fundraising campaign, 1953–1955]. Yihe Shiji, 25 (2015): 36–48. | |

Chew, Wee Kai. “Dashidai de tezheng, beijing buyiban de nanyang daxue zhongwenxi xueren” [A unique context: Scholars of the Nanyang University Chinese faculty in a great era]. Lianhe Zaobao, 2 August 2021. | |

Chew, Wee Kai. “Fengzhi nanyang daxue luocheng dadian bainabei” [The inauguration ceremony of Nanyang University]. Yihe Shiji, no. 40, 16 September 2021. | |

Choi, Kwai Keong. Xinma huaren guojia rentong de zhuanxiang 1945–1959 [The shift in national identity of Chinese in Singapore and Malaya, 1945–1959]. Singapore: Singapore South Seas Society, 1990. | |

Ku, Hung-ting. “Xingma huaren zhengzhi yu wenhua rentong de kunjing: nanyang daxue de chuangli yu guanbi” [The dilemma of political and cultural identity for Chinese in Singapore and Malaya: The founding and closure of Nanyang University]. In Dongnanya huaqiao de rentong wenti: malaiya pian [Identities of overseas Chinese in Southeast Asia: Essays in Malaya], 169–195. Taipei: Linking Publishing Company, 1994. | |

Lee, Guan Kin, ed. Images of Nanyang University: Looking from Historical Perspectives. Singapore: Centre for Chinese Language and Culture, Nanyang Technological University and Global Publishing, 2007. | |

Lee, Leong Sze. “1950 niandai xinjiapo de zhengzhi, jiaoyu yu zhongzu maodun: yi nanyang daxue de chengli wei li” [Political, educational and racial conflicts in Singapore in the 1950s: The founding of Nanyang University as a case study]. Chung-Hsing Journal of History, 17 (2006): 533–551. | |

Lee, Leong Sze. “Cong chuangxiao dao zhixiao: pingjia chenliushi jingying nanyang daxue de linian yu celüe” [From founding to governance: An evaluation of Tan Lark Sye’s philosophy and strategies in the management of Nanyang University]. In Huayu yuxi de renwen shiye: xinjiapo jingyan [Sinophone humanities and the Singaporean experience], edited by David Wang Der-wei. Singapore: Centre for Chinese Language and Culture, Nanyang Technological University, 2014. | |

Lee, Leong Sze. Tan Lark Sye and Nanyang University. Singapore: Centre for Chinese Language and Culture, Nanyang Technological University, 2012. | |

Lee, Yip Lim, Lee Leong Sze et al., eds. Nanyang daxue zouguo de lishi daolu [The historical path of Nanyang University]. Kuala Lumpur: Nanyang University Alumni Association of Malaya, 2002. | |

Leo, Suryadinata. “Nanda yu qi xiaoyou dui xinma de gongxian” [The contributions of Nantah and its alumni to Singapore and Malaysia]. Lianhe Zaobao, 23 September 2016. | |

Nanyang daxue shiliao huibian [The history of Nanyang University]. Kuala Lumpur: Nanyang University Alumni Association of Malaya, 1990. | |

“Nanyang University.” National Library Board, Singapore. | |

Nanyang University 10th Anniversary Commemorative Magazine: 1956–1966. Singapore: Nanyang University, 1966. | |

Pei, Sai Fan. “Nanyang daxue dui xinjiapo de xianshi yiyi” [The significance of Nanyang University to Singapore]. Lianhe Zaobao, 28 December 2023. | |

Teh, Hoon Heng. Teh Hoon Heng’s Nantah Story. Singapore: Centre for Chinese Language and Culture, Nanyang Technological University and Global Publishing, 2011. | |

Zhou, Zhaocheng. The Relationship between Nanyang University and Singapore Government, 1953–1968. Singapore: Centre for Chinese Language and Culture, Nanyang Technological University, 2012. |