Chinese-language textbooks and the transmission of culture

The Chinese language is regarded as one of the core subjects in the curriculum of traditional Chinese-medium schools. This discipline was known by different names in different eras, such as guoyu (national spoken language), guowen (national language), huayu (Mandarin) and huawen (Chinese language). Right from the start, its teaching carried the dual function of language learning and transmitting culture.

Using textbooks to impart moral education

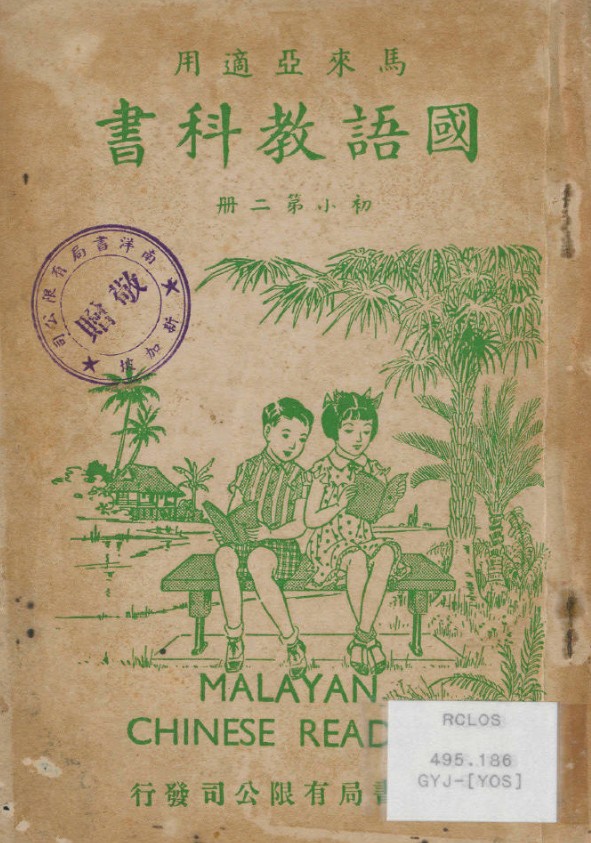

Before the “Malayanisation” of curriculum and textbooks, where content was localised to reflect the distinct characteristics of the region, Singapore’s traditional Chinese-medium schools typically followed the curriculum standards of the late Qing dynasty and China’s Nationalist government, and used textbooks produced by them. These textbooks — from the late Qing’s Mengxue keben (Elementary textbook) to language textbooks published during the early years of Republican China, such as Republican Chinese Language Textbook and New Method Series: Chinese Spoken Language Readers — were intended for students in China, and were compiled by Chinese literati and published by Chinese publishing houses. The style of these textbooks inherited the tradition of China’s classical primers (such as Three Character Classic and Thousand Character Classic), with content encompassing astronomy, geography, history, literature, self-cultivation, ethics and morality. Their purpose was “to broaden students’ knowledge and to serve as a model for writing” by incorporating cultural education in the learning of language.1

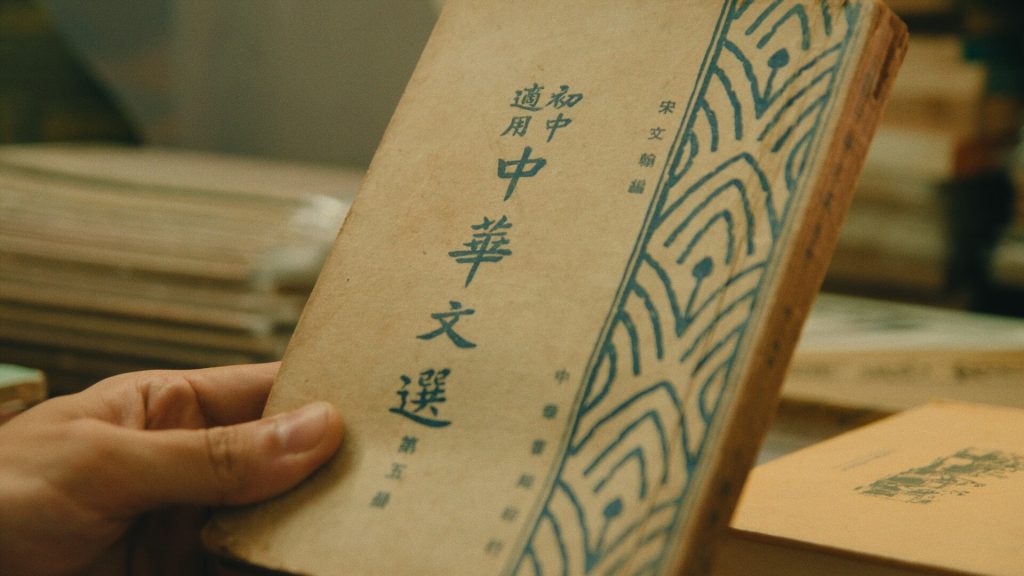

From the early post-war years to the late 1970s, Chinese-medium schools in Singapore and Malaysia widely adopted the book Zhonghua wenxuan [Selected Chinese Texts]. Rich in content, it draws upon traditional Chinese culture (such as Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist philosophies) as well as works by renowned writers throughout Chinese history (such as The Book of Songs, Songs of Chu, and hanfu, a Han dynasty literary form combining features of poetry and prose). Selected Chinese Texts exerted a positive influence on how students in Singapore and Malaysia identified with Chinese culture.

Traditional Chinese culture in Malayanised textbooks

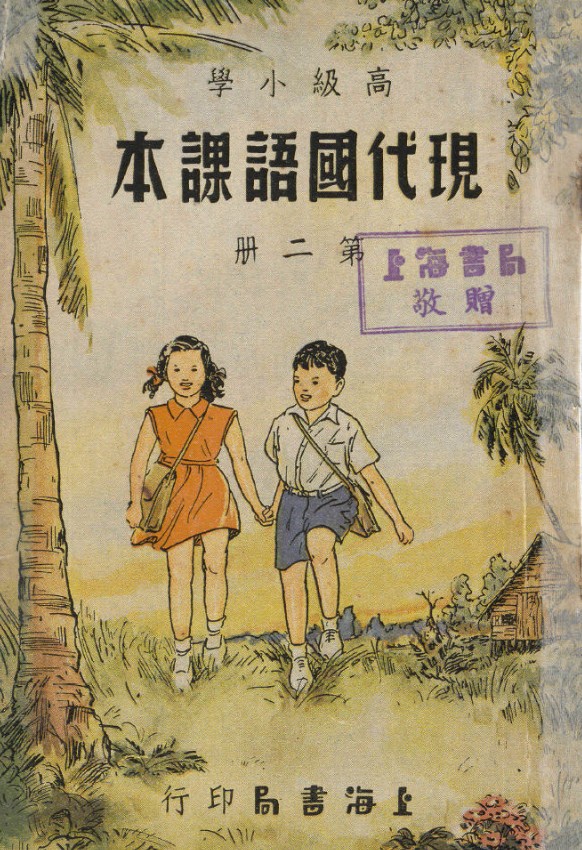

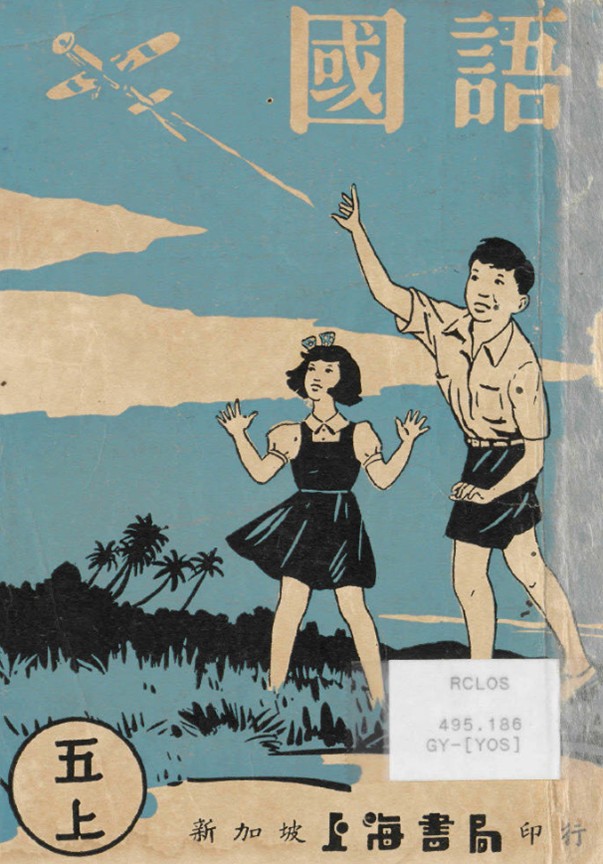

After World War II, the British colonial government implemented a programme to Malayanise curriculum and textbooks in Singapore and Malaya. The primary concern of the local Chinese community was whether Chinese textbooks would retain content on traditional Chinese culture. The Huawen (Chinese Language) textbook series published by the World Book Company included content on King Goujian of Yue Kingdom, explorer Zhang Qian, general Yue Fei, Confucius, the Ming Tomb and Sun Yat-sen Mausoleum. The content was aimed at cultivating good character in students through the deeds of Chinese historical figures and well-known personages. In addition, this series of textbooks contained essays on traditional Chinese festivals and extolled Chinese culture, highlighting the Chinese characteristics of these “language learning” textbooks.2

Confucian thought in Chinese textbooks

After Singapore gained independence in 1965, the government implemented a bilingual policy, which changed the country’s language landscape dramatically. In the early years of nation-building, the Chinese language was designated as either a first or second language in the national education system. During this period, Chinese textbooks were localised and standardised to enhance Singaporeans’ sense of national identity and patriotism. Essays for secondary school Chinese-language textbooks were selected based on the Secondary Chinese Language Syllabus, which emphasised the characteristics of Singapore and Southeast Asia, integrating language learning, literary appreciation and the transmission of cultural and historical knowledge. Hence, apart from retaining content related to Chinese culture, the textbooks also began to include Malaysian Chinese literature. One notable example is the Huawen (Chinese language) series (including textbooks for Chinese as first and second languages for secondary schools and Chinese language for pre-university), edited by Singaporean scholar Lim Chee Then (1939–2019) and published by the Educational Publications Bureau.

Between 1979 and 2011, the government implemented a series of reforms in education and the teaching of Chinese language by conducting several rounds of reviews and revisions of Chinese-language curriculum, textbooks and pedagogy.3 In 2011, it launched a series of textbooks and teaching materials pegged to the standards of Foundation Chinese, Chinese B, Chinese (Normal Academic), Chinese (Express) and Higher Chinese to cater to students of different proficiency levels. This series of textbooks emphasises the motivation in language learning and enhancing communication skills, while the transmission of traditional culture is relegated to a secondary role. Nevertheless, the textbook content remains closely aligned with the focus on “man and self”, “man and society” and “man and nature”. Most of the texts are also about “individual” and “social values”, which resonate with the Confucian philosophy of tian ren he yi (harmony between nature and man).

To make up for the loss of traditional Chinese culture in the language curriculum and help Chinese students grasp the essence of their heritage, the government rolled out several initiatives, including the introduction of the Confucian Ethics subject, Chinese Language Elective Programme and Bicultural Studies Programme.4 Both the 2002 and 2011 Secondary Syllabus Chinese Language Syllabus emphasise the long history of Chinese culture, while the teaching materials also incorporate content such as primers on well-known historical figures, traditional festivals and customs, as well as literary appreciation. Teachers are expected to leverage such content to nurture students’ moral character and instil in them the fine values of traditional Chinese culture.5

In a nutshell, incorporating cultural and moral education has been a tradition in the teaching of Chinese language in Singapore. Whether it was during the era when traditional Chinese education flourished or after the implementation of the bilingual education policy in post-independence Singapore, the teaching of Chinese has always carried the dual mission of developing language skills and fostering values. Before the Malayanisation of textbooks, Chinese-language teaching relied on guowen and guoyu textbooks to comprehensively educate students on China’s traditions and culture. After textbooks became Malayanised, especially following Singapore’s independence, Chinese-language teaching sought to strike a balance between the instrumental and cultural functions of language education. In addition to developing language skills, such textbooks also help students learn more about their traditional culture, and in turn identify with Singapore’s core values and become loyal and patriotic citizens.

This is an edited and translated version of 寓教于文:华语文教科书与文化传承. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Refer to “Bianji dayi” [Editorial Notes], in Mengxue keben [Elementary textbook] (Shanghai: Nanyang Public School, 1897). |

| 2 | Guoyu [National spoken language] (Singapore: United Publishing House, 1953–55); Huawen [Chinese language] (for Chinese-medium primary schools) (Singapore: Educational Publications Bureau, 1961–62); Huayu (di er yuwen) [Mandarin as a second language] (Singapore: World Book Company, 1967). |

| 3 | See Lee Ching Seng, “Xinjiapo huawen jiaokeshu daolun: shehui jiwang yu jiaoyu, jiaoyu jiwang yu jiaokeshu” [An overview of Chinese textbook publishing in Singapore], Pages that Opened Our Minds III: A Pictorial Catalogue of Early Chinese Textbooks in Southeast Asia, edited by Kuay Ying Xuan (Singapore: Chou Sing Chu Foundation, 2020), 16–17. |

| 4 | The Chinese Language Elective Programme (CLEP) is offered by selected secondary schools and junior colleges to nurture students who have an interest and aptitude in Chinese language and literature. The Bicultural Studies Programme was launched in 2005 to nurture bilingual and bicultural talent who can engage in both Chinese and Western cultures, while having local awareness and international perspective. Students under the Bicultural Programme have the opportunity to participate in a variety of learning activities, such as seminars and lectures on Chinese general knowledge. |

| 5 | Curriculum Planning & Development Division, MOE, 2011 Syllabus Chinese Language Secondary (Singapore: MOE, 2010), 31. |

Kuay, Ying Xuan, ed. Pages that Opened our Minds III: A Pictorial Catalogue of Early Chinese Textbooks in Southeast Asia by World Book Company. Singapore: Chou Sing Chu Foundation, 2020. | |

Lim, Chee Then. Cong wenhua jiaoyu fazhan de jiaodu, kan dongfang chuantong zai xinjiapo jinhou de yanbian [The evolution of Chinese tradition in Singapore from a cultural and educational perspective]. Singapore: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 1986. | |

Lim, Chee Then. Huawen jiaoxue yu chuantong jiazhiguan de peiyang [The teaching of the Chinese language and the cultivation of traditional values]. Singapore: Department of Chinese Studies, National University of Singapore, 1987. | |

Shu, Xincheng, ed. Jindai zhongguo jiaoyu shiliao [The history of education in modern China]. Shanghai: Shanghai Scientific & Technical Publishers, 2015. |