Local lexicon: The different Chinese characters for ‘durian’

The Chinese term for the tropical fruit durian, 榴梿 (liulian), was already widely used in Nanyang (Southeast Asia) before 1980s. Throughout history, the sound liulian has been represented in various ways using different Chinese characters, until it eventually settled on one that conformed to the norms of Chinese word formation.

Sound over meaning

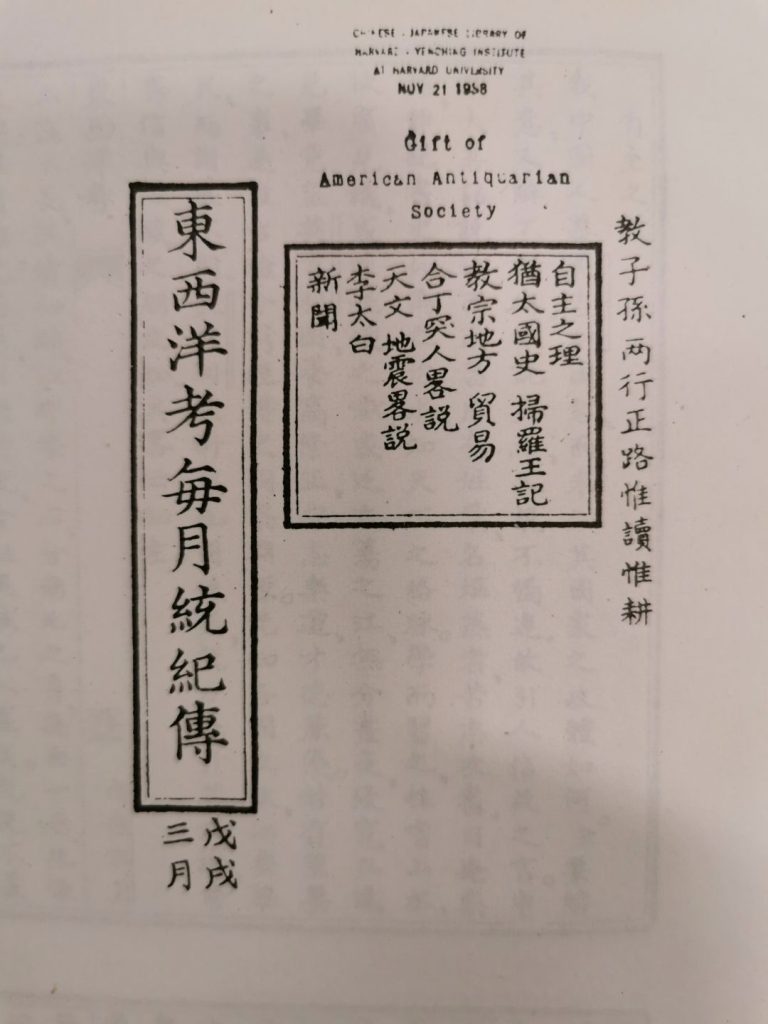

The earliest documented use of a Chinese term for “durian” appeared in April 1838 in the Eastern Western Monthly Magazine published by a Christian church in Singapore. It was written as 流连, which was simply a transliteration of “durian” as its two characters had nothing to do with fruit. This was also in line with the habit of the Nanyang Chinese then, to transliterate words based on dialect pronunciations.

The Chinese-language newspaper Lat Pau, founded in 1881, often wrote durian as 榴连. In this combination, the left radical of the first character 榴 is the Chinese word for wood (木), indicating a deliberate choice by the editors who likely wanted a character that could reflect the fact that durian grows on trees. From the perspective of Chinese linguistics, this was a marked improvement from 流连, whose characters only reflected the sound of liulian but not the meaning of the word.

In the early 20th century, many more Chinese-language newspapers were founded in Singapore, but there was no standard form for liulian. Notably, the combination 榴莲 appeared for the first time during this period, made up by one character with the “wood” radical (木), and the other with the “grass” radical (艹). It may have been a conscious or unconscious editorial decision to use both characters with radicals that are related to plants.

Variance and conformity

In the 1920s, two major Chinese-language newspapers in Singapore, Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh, were founded. From the time of their establishment until before World War II, they seemed to have come to a consensus on using 榴莲 to refer to liulian. By this time, the use of 榴连 had become rare.

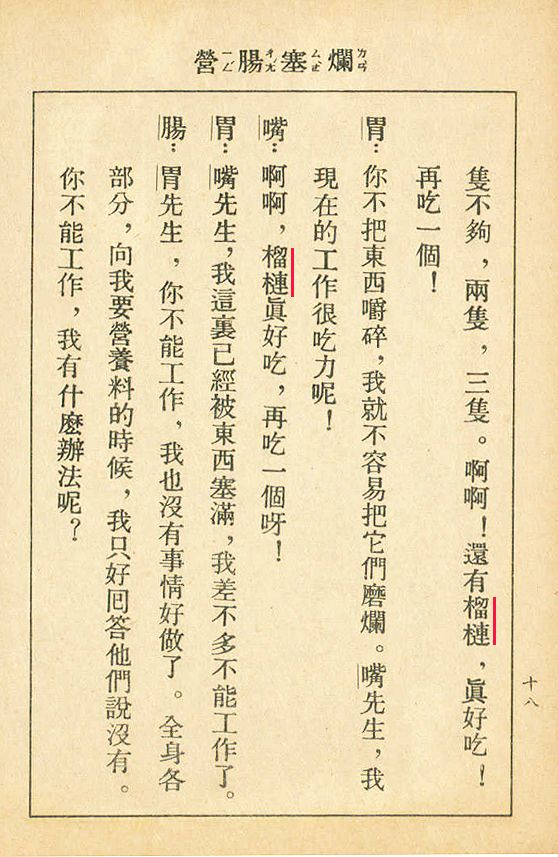

In Singapore, Chinese-language textbooks are crucial to the regulation and standardisation of Chinese terms. Before World War II, these textbooks were edited and published in China. Chung Hwa Book Company and The Commercial Press were two major Chinese publishers involved in the production of these textbooks. Both companies had excellent language specialists and took the initiative to modify Chinese terms used in Southeast Asia to suit Chinese linguistic norms. In the second volume of the Reviving Chinese Language Textbook published by The Commercial Press in 1947 for lower primary students, a passage on durians used the characters 榴梿 to refer to the fruit. This was the first documented appearance of the character “梿” (pronounced lian) which contained the wood radical (木).

After World War II, Singapore’s Ministry of Education stipulated that the content of textbooks had to be localised. Following the release of the Fenn-Wu Report in 1951, Malayanised curriculum content became the benchmark for textbooks used by local Chinese-medium schools. Singapore’s textbooks were no longer edited and published in China. Five local publishers — World Book Company, Shanghai Book Company, Nanyang Book Company, The Commercial Press, and Chung Hwa Book Company — began publishing local Chinese-language textbooks. These textbooks continued to use 榴梿 for durian, driving the adoption of this as the standard form.

There were also more and more newspaper reports on durians after World War II. In the late 1940s, 榴梿 appeared only twice in the two major Chinese-language newspapers. In the 1950s, it had appeared 40 times. The version 榴莲, by contrast, was used over 900 times during the same period. This might explain why 榴莲 was later chosen as the main version in the entry for “durian” in Xiandai Hanyu Cidian (A Dictionary of Current Chinese; Contemporary Chinese Dictionary), first published in China in 1978.

In the 1960s and 70s, there was a reversal in the usage in newspapers, with 500 instances of 榴梿, and the use of 榴莲 dwindling to 200 instances. The variant 榴连 meanwhile appeared only 80 times during this period. The more frequent usage of 榴梿 could have been attributed to the generation of people who had been educated in the 1950s with localised textbooks. In magazines, the usage was looser, with either 榴连 or 榴莲 being used.

From the use of the different forms within the same time period, we could see that no standard version for liulian had emerged yet.

In the late 1980s, the question of which characters to use for durian became the subject of much debate. It came about from Xiandai Hanyu Cidian, an authoritative dictionary of the Chinese language published in China. Its first edition in 1978 and second edition in 1984 both used 榴莲 as the entry for durian. This caused an uproar in Singapore. Many wrote to the Chinese papers, questioning the use of 莲 (with the grass radical) instead of 梿 (with the wood radical). Many staunchly defended the “legal status” of 榴梿, but there were also some who did not mind going with the flow and using 榴莲 instead.

Many of those involved in the debate based their opinions on personal preference rather than academic theory or linguistic history. As such, the controversy did not lead to an awakening in terms of a deeper engagement with the relevant theories. However, it did, to some extent, inspire a greater sense of identification with the Singapore Chinese language.

In 2012, the sixth edition of Xiandai Hanyu Cidian featured 榴梿 as the main entry for durian, while 榴莲 (the form which is used more widely in China), was listed as a secondary variant. The editors had apparently taken note of the opinions of Singaporean and Malaysian academics, and decided to make a choice that was to everyone’s satisfaction.

This is an edited and translated version of 【本土语汇】“榴梿”与“榴莲”. Click here to read original piece.

Hsu, Yun Tsiao. Wenxin diaochong [Reflections on language]. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1973. | |

Khoo, Kiak Uei. Malaixiya huayu yanjiu lunji [Collected writings on Malaysia’s Chinese language studies]. Kuala Lumpur: Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies, 2018. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Lunxue zazhu conggao [Collected writings of Lim Buan Chay]. Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2017. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Yuyan wenzi lunji [Collected writings on language]. Singapore: National University of Singapore Department of Chinese Studies, 1996. | |

Lim, Earn Hoe. Wocheng woyu: xinjiapo diwenzhi [Our city, our language: Chronicling Singapore’s Chinese language heritage]. Singapore: Great River Book Co., 2018. | |

Wong, Wai Tik. Shicheng yuwen xiantan [Languages in Singapore]. Singapore: Federal Publications, 1995. |