Local lexicon: The various names of Nanyang kopi

Coffee originated in the Arab region, where it is known as qahwa. The term for coffee in most other languages hence resembles the pronunciation of qahwa — “coffee” in English, kopi in Malay, and 㗝呸 (gaopei), which was used by the Chinese in Southeast Asia.

The history of coffee as a cash crop and beverage in Southeast Asia began in Indonesia. The origin and development of the present-day Chinese term for coffee, 咖啡 (kafei), can thus be traced through its spread among the Indonesian Chinese community.

The earliest record of the Chinese term for coffee can be found in the Annals of Batavia, an 18th century account of the Chinese community in Indonesia. It mentions the history of coffee transplantation in Java, and refers to coffee as 高丕 (gaopi).

Origins of gaopi

The term gaopi was used widely by the Chinese community in Java, Indonesia after the Dutch began planting coffee there on a large scale from the early 18th century.

In a document on the social governance of the early Chinese community in Indonesia, an account of a legal trial in 1790 uses the term 高丕茶 (gaopi cha) to refer to coffee. Gaopi was derived from the Hokkien transliteration of the Dutch word for coffee, koffie. As the Hokkien dialect does not have labiodental consonants such as “f” (articulated with the lips and teeth), the bilabial sound pi (made using both lips) was used instead. Meanwhile, cha in Hokkien refers to edible liquids in general, suggesting that when coffee was introduced to the Chinese community, it was used to indicate that coffee was a type of beverage. By the 19th century, the same records no longer contained the term gaopi cha. Instead, 高丕 (gaopi) and 戈丕 (gepi) were used.

The rise of kafei in Singapore

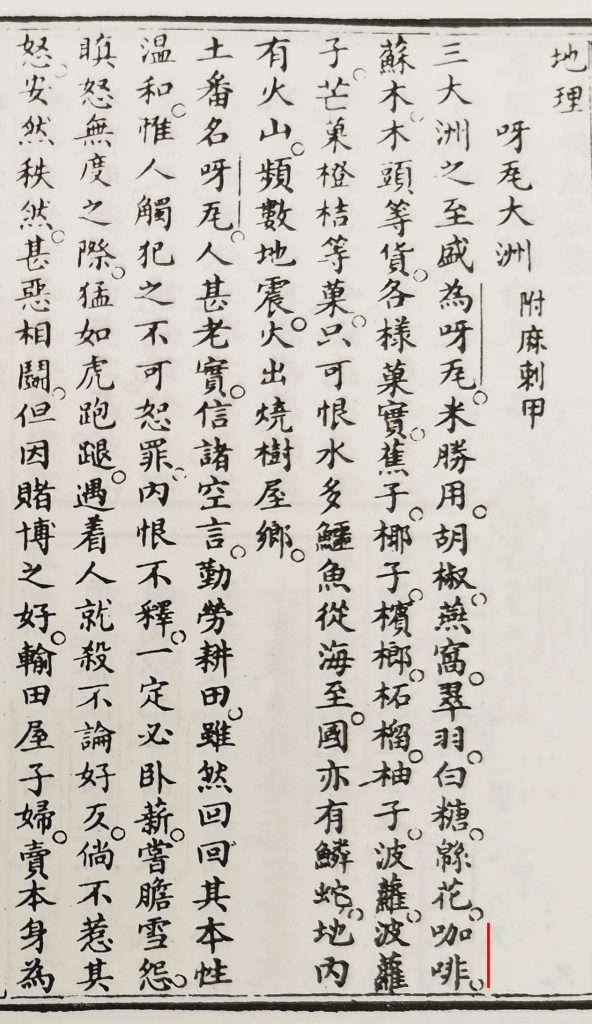

The earliest record of 咖啡 (kafei) — the Chinese term for coffee today — can be found in an October 1837 article in Singapore’s Eastern Western Monthly Magazine titled “Yawa dazhou” (Java Continent). However, a short passage on Singapore’s agricultural development published in the same magazine not long after, in the first lunar month of 1838, still used the earlier version, 高丕 (gaopi).

In 1882, Gustave Schlegel (1840–1903), a Dutch sinologist in Indonesia, compiled the bilingual dictionary Nederlandsch-Chineesch Woordenboek. Under the Dutch word koffie, he listed the terms kafei (coffee), kafei cha (coffee beverage), kafei dian (coffee shop), and kafei zi (coffee seed), among others. While the term 咖啡 (kafei) was used, it was meant to be pronounced as kopi, which followed the Hokkien pronunciation. The Dutch term gezette koffie (brewed coffee) meanwhile corresponded to the term kafei cha, showing that the Chinese community in Indonesia at the time still used cha to signify beverages.

Although 咖啡 (kafei) had appeared in Singapore as early as 1837, another variation 㗝呸 (gaopei) was more commonly used within the community. It could be seen on coffee shop signs along the streets, which reflected the linguistic landscape in the early 19th to mid-20th century Singapore.

How did 咖啡 (kafei) become the standard written form for coffee in Singapore? This can be partly traced to the usage of the term in Singapore’s early Chinese-language newspapers, such as Lat Pau (founded in 1881), Thien Nan Shin Pao, Chong Shing Yit Pao, Union Times, Cheng Nam Jit Poh, and Sin Kuo Min Press. In these papers, 羔丕 (gaopi) was the most common term for coffee. Other variations were 㗝呸 (gaopei), 咖啡 (kafei), and 架啡/加啡 (jiafei).

Coffee shops grew more common in Singapore in the 1920s, and the same period saw the founding of the Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh. From the time of their founding until they ceased publication during the Japanese Occupation in 1942, these two newspapers used 羔丕 (gaopi) and 咖啡 (kafei) with roughly equal frequency, besides featuring other variations. One Nanyang Siang Pau article on 29 May 1931 contained three variations for coffee in the same piece — a striking reflection of Singapore’s unique linguistic environment. After World War II, the use of 咖啡 (kafei) increased steadily in Nanyang Siang Pau and Sin Chew Jit Poh, while 羔丕 (gaopi) was used less frequently. After 1976, 羔丕 (gaopi) virtually disappeared from the Chinese-language newspapers.

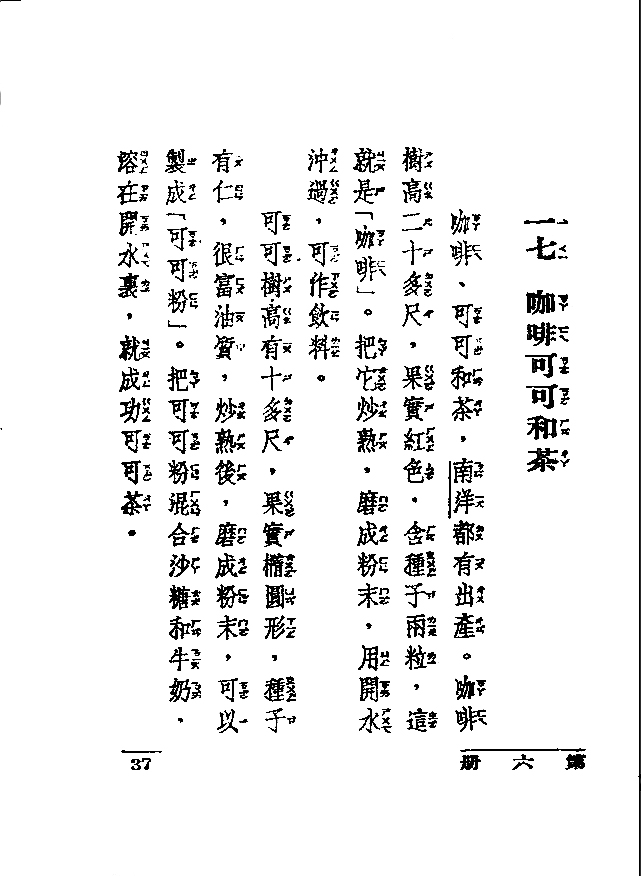

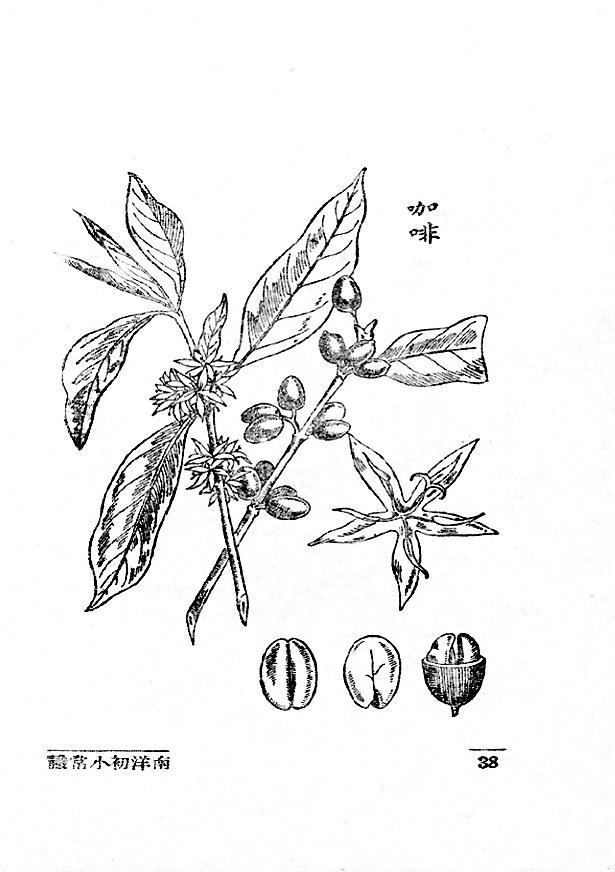

Chinese-medium schools and textbooks also played an important role in standardising the Chinese language in Singapore before independence. In 1947, Nanyang Book Company published Nanyang changshi jiaokeshu’s (Nanyang General Knowledge Textbook) Lower Primary Level Book 6, where 咖啡 (kafei) was used in a passage on coffee. Subsequently, all textbooks used this term, which probably contributed to its acceptance as the standard term for coffee in Singapore.

There are two main takeaways from the evolution of the term for “coffee” in Singapore. First, as Mandarin was not an official language during the colonial period and there were no official efforts to standardise it in Singapore, many Chinese variants of the word “coffee” existed. Second, the strong influence of Chinese dialects on the Mandarin in Singapore explains why 羔丕 (gaopi) — steeped in dialect flavour — was common in Chinese-language media and everyday conversation.

This is an edited and translated version of 【本土语汇】从南洋“㗝呸”到“咖啡”的演变. Click here to read original piece.

Hsu, Yun Tsiao. Wenxin diaochong [Reflections on language]. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 1973. | |

Khoo, Kiak Uei. Malaixiya huayu yanjiu lunji [Collected writings on Malaysia’s Chinese-language studies]. Kuala Lumpur: Centre for Malaysian Chinese Studies, 2018. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Lunxue zazhu conggao [Collected writings of Lim Buan Chay]. Singapore: Xinhua Cultural Enterprises, 2017. | |

Lim, Buan Chay. Yuyan wenzi lunji [Collected writings on language]. Singapore: National University of Singapore’s Department of Chinese Studies, 1996. | |

Lim, Earn Hoe. Wocheng woyu: xinjiapo diwenzhi [Our city, our language: Chronicling Singapore’s Chinese language heritage]. Singapore: Great River Book Co., 2018. | |

Wong, Wai Tik. Shicheng yuwen xiantan [Languages in Singapore]. Singapore: Federal Publications, 1995. |