Mandarin phonetic symbols in Singapore

As early as the 19th century, the Chinese community in Singapore established many private schools that focused on teaching the Four Books and Five Classics, central texts associated with Confucianism. Lessons at these institutions were mainly conducted in Chinese dialects. In the early 20th century, revolutionary movements and reforms initiated by Kang Youwei (1858–1927) and Liang Qichao (1873–1929), scholars from China, spurred various Chinese dialect organisations to set up schools that offered new models of education in Singapore. With the founding of Republican China, Singapore’s Chinese-medium schools viewed promoting Chinese culture as their mission and entered a robust phase of development. From 1919 onwards, these schools were influenced by China’s national language movement and gradually switched to teaching in Mandarin.1

Teaching the Chinese language required teaching the phonetic transcription of Chinese characters. In Singapore, different systems of phonetic transcription have been adopted during different time periods. These included zhiyin (which indicated pronunciation using homophones), fanqie (which indicated the pronunciation of a monosyllabic character by using two other characters), zhuyin (which used phonetic symbols), and hanyu pinyin (which uses a romanised phonetic alphabet).

Early phonetic systems: Zhiyin and fanqie

Before the end of the Qing dynasty, the zhiyin and fanqie systems were used for the phonetic transcription of Chinese characters. The zhiyin system used another character with an identical pronunciation (a homophone) to indicate the pronunciation of a character. For example, the pronunciation of the character 郝 (hao) would be indicated using the character 好, which is pronounced the same way. In the fanqie system, the pronunciation of a character is indicated using a character with the same initial consonant, and another character with the same medial and final sounds. For example, the character 东 (dong) is transcribed by combining the initial consonant of the character 德 (de) and the medial and final sounds of the character 红 (hong). The fanqie system was used in ancient times.

Zhuyin phonetic notation

In 1912, the then-Ministry of Education in China held an education conference and decided on the use of phonetic symbols. After many revisions, this system was officially adopted in April 1930 as a way to transcribe the Mandarin pronunciation of Chinese characters. These phonetic symbols resembled the constituent strokes of Chinese characters and were reminiscent of Chinese calligraphy. For example, the symbol for the sound “bo” was ㄅ, while ㄆ stood for “po”, ㄇ for “mo”, and ㄈ for “fo”. This system was not easy to grasp. Nevertheless, from the 1930s onwards, most Chinese-medium schools in Singapore used this system to teach the Chinese language, and those born in the 1950s who attended these schools learned these phonetic symbols.

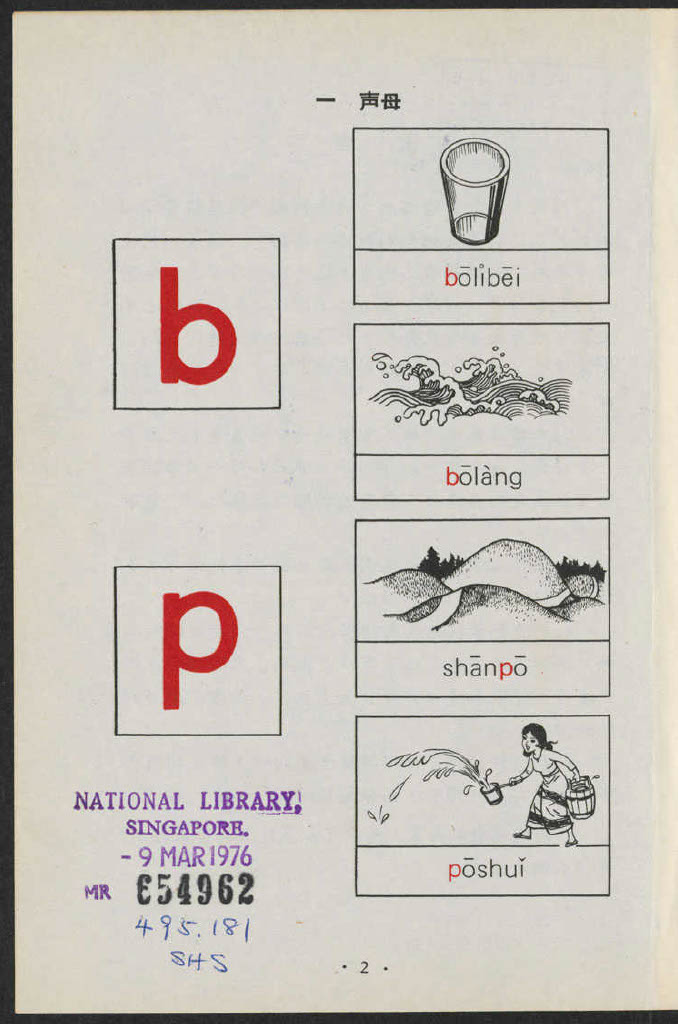

Promotion and implementation of the Hanyu Pinyin Scheme

In February 1958, the Chinese government approved the Hanyu Pinyin Scheme, which uses the 26 letters of the Latin alphabet to transcribe the pronunciation of Chinese characters. This replaced the phonetic symbol system, which was difficult to learn, read, and remember. In 1971, hanyu pinyin was introduced in Singapore. In 1974, the Ministry of Education announced that hanyu pinyin would replace the longstanding phonetic symbol system. By 1979, hanyu pinyin was adopted across the board to teach the Chinese language, and the phonetic symbol system was phased out of the education system.

The local adoption of hanyu pinyin was not without its challenges. Singapore’s bilingual policy requires students to learn English and their Mother Tongue, which meant that Singaporean Chinese students had to learn how to pronounce and write both the English and hanyu pinyin alphabet. However, because the pronunciation of both alphabets are not identical, educators and parents at the time were concerned that learning hanyu pinyin would hamper students’ learning of English. In 1980, the Ministry of Education stipulated that students would only learn hanyu pinyin from Primary Four to Primary Six. After over 10 years of experimentation, it was found that no significant issues arose when students learned English and hanyu pinyin simultaneously. Hence, from 1992 onwards, schools could decide if they wanted their students to start learning hanyu pinyin a year or two earlier. A year later, the Ministry of Education decided that students could start learning hanyu pinyin in Primary One, before they were taught to read Chinese characters.

Hanyu pinyin did not solve all the issues associated with the phonetic transcription of Chinese characters. For example, when transcribing a Chinese phrase or proverb comprising several characters, should each character be presented as separate words or be joined without any spaces in between? Other common concerns that educators had included: How should phrases ending with the non-syllabic final “r” (儿) or in neutral tones be transcribed? What were the rules for transcribing names?

Subsequently, China established the Hanyu Pinyin Orthography, which was used together with the Hanyu Pinyin Scheme. The Chinese government later set the Basic Rules of Hanyu Pinyin Orthography as its national standard. The latest version of this publication has been in use since 1 October 2012, providing clear rules and definitions for various issues related to how hanyu pinyin should be written.

Now, the teaching of hanyu pinyin in Singapore’s primary schools broadly follows rules set by China. For instance, the new editions of the Chinese textbook Huanle Huoban (Versions 1.0 and 2.0) for primary school students use word-segmented writing. However, since Singapore Mandarin has its own distinct characteristics, various aspects of phonetic transcription here differ from those used in China. For example, the final “r” is not commonly used in Singapore, so its phonetic transcription is flexible. Proverbs are also transcribed without hyphens. Additionally, the first letter in a transliterated Chinese surname is capitalised while the transliteration of one’s given name can be presented as separate words or combined. Most Chinese-language educational materials here choose to combine the transliterated characters of Chinese given names, while both variations can be found in official identity documents.

In December 2015, the International Organisation for Standardisation established international standards and rules for word-segmented writing and automatic transcription in hanyu pinyin as international standards. Singapore was the first country to adopt these standards, marking a milestone in the history of Singapore Chinese education.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡华文注音方式的演变. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Eddie Kuo and Luo Futeng, Unity in Diversity: Language and Society in Singapore (Singapore: Global Publishing, 2022), 115. |

Tan, Yao Sua. Huayu yuyin jiaoxue shuolun [Teaching of Mandarin phonics]. Singapore: Candid Creation Publishing, 2005. | |

Wang, Shiming. Huayu zhuyin fuhao [Mandarin phonetic symbols]. Singapore: Siang Kang Publishing Service Co, 1979. |