Chinese newspapers in pre-war Singapore (1845–1941)

It has been said that the first Chinese newspaper in Singapore was Tifang Jih Pao (Local News), published in 1845, followed by Jit Sheng (Rising Sun) in 1858. However, according to research by the academic Chng Khin Yong, there is currently no evidence to support the existence of the former, and the only proof that the latter existed is an advertisement found in the Straits Government Gazette.1 The earliest-known Chinese daily newspaper in Singapore is Lat Pau, which was founded in 1881.

Before World War II, there were about 20 noteworthy Chinese newspapers in Singapore. They can be sorted roughly into three periods based on their historical backgrounds, their founder’s objectives, the editorial policies adopted by chief writers or editors, the focus of their content, and the social functions they served.

Promoters of Confucianism and nationalism (1881–1901)

As Singapore developed into a shipping hub in the last two decades of the 19th century, Chinese newspapers managed by the local Chinese community started to emerge. This was due to the following combined factors: the dramatic increase of Chinese population, the emergence of wealthy and middle-class Chinese communities, along with a rise in literacy, the influence of local English newspapers, the prevalence of Chinese newspapers from Hong Kong and Shanghai, and a willingness to invest more time and money in cultural pursuits by the population.2

As a result, four Chinese newspapers emerged during this period. They were: Lat Pau (1881–1932), Sing Po (1890–1899), Thien Nan Shin Pao (1898–1905) and Jit Shin Pau (1899–1903). At the time, nationalism that emphasised loyalty to one’s motherland and Confucianism were the mainstream ideologies of the Chinese communities in Singapore and Southeast Asia. These four newspapers had a common goal: promoting Confucianism and nationalism. The three most prominent journalists at the time were Yeh Chih Yun (1859–1921), Lim Boon Keng (1869–1957), and Khoo Seok Wan (1873–1941). They were advocates of nationalism and actively championed the Confucian revival movement throughout their lives.

See Ewe Lay, the founder of Lat Pau, came from a Peranakan family in Malacca. His family had business ties in Xiamen, and their sense of identity was more closely tied to their ancestral homeland in China. Lat Pau’s editor, Yeh, was also a learned writer from China’s Anhui province. The newspaper thus focused on reporting society news in the Nanyang region and political news from China. Its main objective was to advocate for nationalism and Confucianism through its editorials. With the support of the Chinese Consul at that time, Huang Tsun-hsien (1848–1905), Lat Pau also became a platform for Nanyang literature.3 In 1906, the newspaper introduced supplementary pages with content relating to popular culture, including Cantonese folk ballads, humorous pieces, short commentaries, poetry, and essays. These set a precedent for subsequent Chinese newspaper publications in Singapore and Malaya, which also played a role in the promotion of local Chinese literature.

Sing Po, which came later, was published by Koh Yew Hean Press. Its founder, Lin Hengnan (also known as Lim Kong Chuan, 1844–1893), was an immigrant from Kinmen, a group of islands east of Xiamen. At one point, Wong Nai Siong (1849–1924), who had previously passed the imperial examination, served as the newspaper’s chief editor. Sing Po’s efforts in promoting Confucianism were even more prominent than those of Lat Pau.

Born out of the First Sino-Japanese War which took place between 1894 and 1895, Thien Nan Shin Pao and Jit Shin Pau were founded by Khoo Seok Wan and Lim Boon Keng respectively. These two newspapers were the main forums where the nationalist movement was promoted in the late 19th century. Jit Shin Pau also published a series of scientific and educational articles written by famous Western authors, translated and edited by Lim. Special attention was also given to the activities of Chinese Philomathic Society — a group founded by Lim — and the Confucian revival movement.

Mouthpieces of royalists and revolutionaries

By 1890, the rapidly-changing situation in China was attracting more and more attention from Chinese communities in Southeast Asia. Khoo, a supporter of the reformist movement, founded Thien Nan Shin Pao (1898–1905) to advance the movement’s ideas. Later, newspapers such as Thoe Lam Jit Poh (1904–1905), The Union Times (1905–1947), Chong Shing Yit Pao (1907–1910), Sun Poo (1908–1910) and Nan Chiau Jit Pao (1911) emerged to support either the royalist camp or the revolutionaries, and competed to influence public opinion.

The original edition of Thoe Lam Jit Poh, the first revolutionary newspaper in Singapore, is now lost. Jointly started by Teo Eng Hock (1872–1959) and Tan Chor Lam (1884–1971), the newspaper ceased publication due to poor sales and depleted funds. In 1907, Teo and Tan made a comeback under the guidance of Sun Yat-sen (1866–1925) and founded Chong Shing Yit Pao to advocate revolutionary ideas and compete with The Union Times, a royalist newspaper. Chong Shing Yit Pao was also the first Chinese newspaper in Singapore to publish political cartoons, which featured anti-Qing sentiments.

After the 1911 Revolution, reformists and revolutionaries also founded newspapers such as Cheng Nam Jit Poh (1913–1920), Kok Min Yit Poh (1914–1919), The Sin Kuo Min Press (1919–1940) and Min Kuo Jih Pao (1930–1935). Edited by Khoo, Cheng Nam Jit Poh supported the military government, led by Duan Qirui (1865–1936) after the death of Yuan Shikai, and opposed Sun and the Kuomintang. On the other hand, The Sin Kuo Min Press, Min Kuo Jih Pao, and Cheng Nam Jit Poh were overseas party newspapers of the Kuomintang. The Sin Kuo Min Press, a continuation of Kok Min Yit Poh, went on to become one of the most influential newspapers in the Nanyang region.

Upholders of commercial interests (1923–1941)

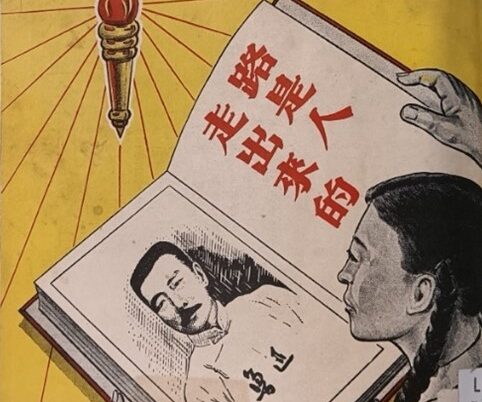

In the period after 1920 and before the fall of Singapore and Malaya, newspapers founded by wealthy Chinese businessmen, such as Nanyang Siang Pau (1923–1941), Sin Chew Jit Poh (1929–1941), and Sin Chung Jit Poh (1935–1941), became the mainstream product in Singapore’s Chinese newspaper industry. These three commercial newspapers were engaged in advocating the war of resistance and national salvation, with a focus on Southeast Asia. Their mutual competition led to the creation of many innovative features, such as free, well-illustrated literary supplements, weekly supplements, themed issues and New Year’s special issues. The Nanyang Yearbook and Sin Chew Jit Poh’s annual publications, as well as literary supplements such as Nanyang Studies and Nanqiao Education, included many historical documents related to Singapore and Malaya.

When the Second Sino-Japanese War broke out in 1937, turbulence in China drove many Chinese intellectuals to Southeast Asia. They eventually joined the Chinese newspaper industry in Singapore, raising the standards of its newspapers. But the outbreak of the Pacific War on 7 December 1941 led to the suspension of Chinese newspapers within the month. The Japanese occupation of Singapore marked the end of an era for an industry that had begun in 1845. After the end of World War II, Chinese newspapers resumed publication, ushering in a new era where they flourished even further.

This is an edited and translated version of 战前重要的新加坡华文报章(1845-1941). Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Chng Khin Yong, “Ri sheng bao yan jiu” [A note on the Chinese newspaper Jit Sheng] in Xinjiapo huaren shi luncong [Collected essays on the Chinese in 19th-century Singapore] (Singapore: South Seas Society, 1986), 88. |

| 2 | Chen Mong Hock, The Early Chinese Newspapers of Singapore 1881–1912, 15–20. |

| 3 | Lee Ching Seng, “Singapore’s Changing Role in Early Printing in the Chinese Language, 1925–1902”, in Chapters on Asia: Selected Papers from the Lee Kong Chian Research Fellowship (2014–2016), edited by National Library Board Singapore (Singapore: National Library Board, 2018), 74–75. |

Chen, Mong Hock. The Early Chinese Newspapers of Singapore 1881–1912. Singapore: University of Malaya Press, 1967. | |

Choi, Kwai Keong. Xinjiapo huawen baokan yu baoren. [Singapore Chinese newspapers and journalists]. Singapore: Hai tian wenhua qiye, 2007. |