History of Chinese tabloids in Pre-Independence Singapore

Tabloids are newspapers that are typically smaller and more compact than daily broadsheets. They usually have a simpler layout and are sold at cheaper prices, and feature a wide range of content, including news, entertainment, commentaries, poetry, essays, novels, and reader submissions. While broadsheets strive for a formal, authoritative tone, tabloids have more editorial freedom, using more colloquial language and focusing on light, entertaining topics that interest the man on the street.

Chinese tabloids in Singapore and Malaysia generally inherited the format and style of tabloids in China, such as brevity and a colloquial tone. They were usually printed in quarter or eighth-sheet formats,1 and featured mainly light, entertaining content. Distribution models varied — some tabloids were published every three days, some every five days, and some weekly.

Readers and writers

Given Singapore’s multiethnic, colonial backdrop, its Chinese tabloids developed quite differently from those in China. Singapore’s Chinese tabloids were mainly commercially driven and aimed to attract readers by appealing to the needs of ordinary people and reporting on topics that resonated with the masses. Hence, most of their readers were workers, farmers, and women employed in the entertainment industry — including singers and dance hostesses who read the tabloids for leisure and used the entertainment columns in these publications to boost their popularity.2

Birth of Singapore’s Chinese tabloids (1925–1934)

Influenced by China’s New Culture Movement, Chinese newspapers and supplementary periodicals in Singapore and Malaysia shifted their focus towards intellectual and cultural topics in the 1920s. Lighter forms of content were shunted into the sidelines, although they continued to see demand from ordinary readers. Seeking new ways to engage with popular culture, readers turned to the tabloids, which became an important medium for alternative voices.

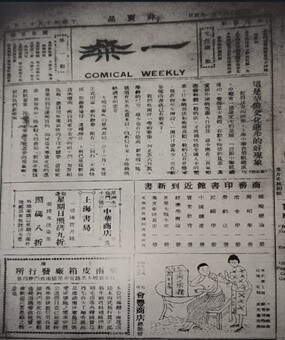

Singapore’s Chinese tabloids flourished during this period. The first tabloid was launched in 1925,4 and many more swiftly followed. From 1925 to 1929, an estimated 73 to 89 tabloids were published in Singapore.5 This was the first peak period for tabloids in Singapore and Malaysia, with notable publications including Yi Xiao Bao, Comical Weekly, Chi Tien and Marlborough Weekly.

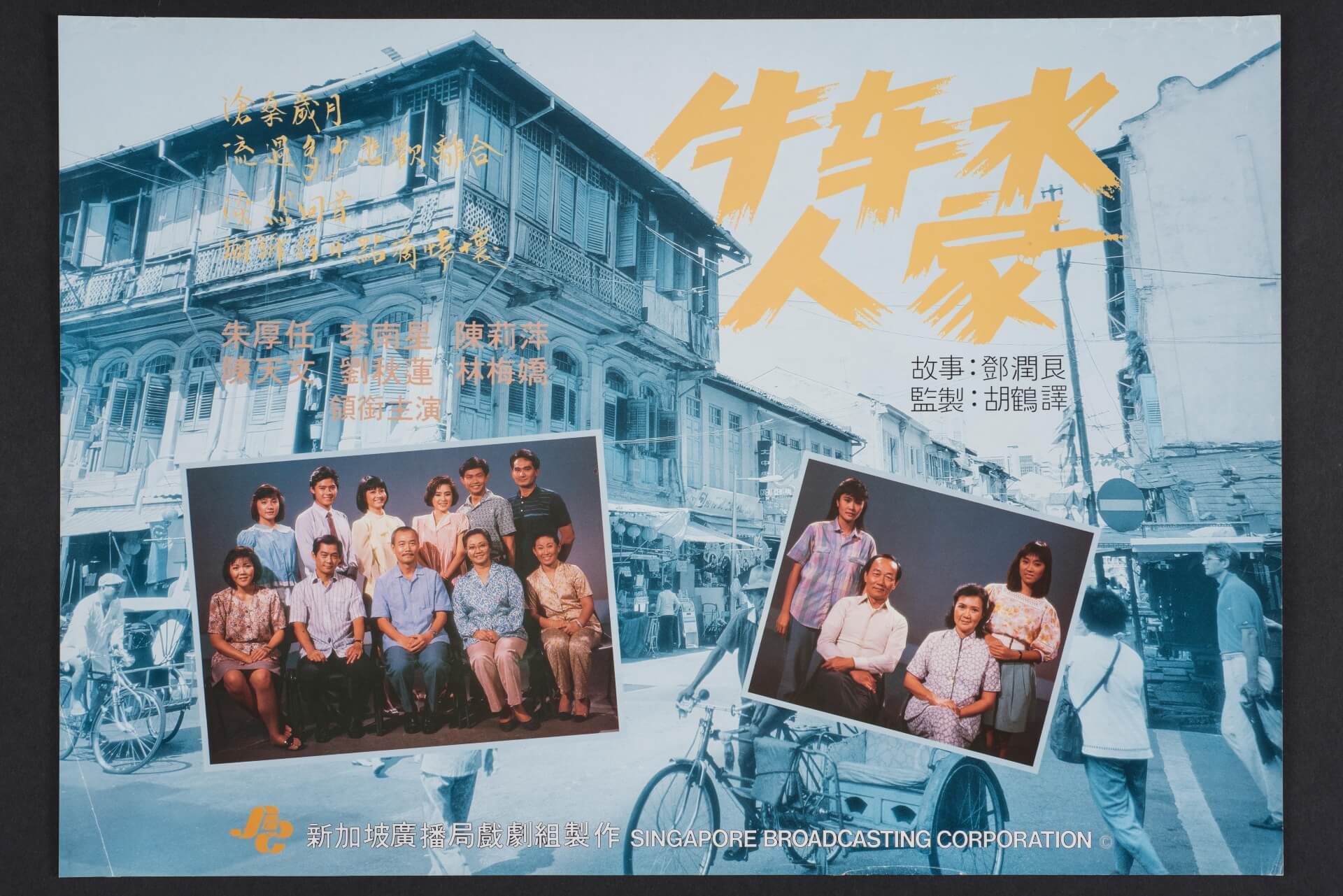

Second golden age (1940s–1950s)

After World War II, Chinese tabloids entered a second golden age, and at least 40 were published during this period. These included Kang Pao, Feng Pao, Shieh Pau, Ti Press, Tah Chong Pau, and Life News.6 Tabloids such as Sin Lit Pau and Yeh Teng Pao were, at one point, able to sell tens of thousands of copies annually.7

However, this golden age did not last for long. As the newspaper industry underwent structural changes, tabloids faced many challenges. Financial pressure increased as printing costs rose, and a shortage of paper and other materials persisted. Many newspapers did not survive.

As tabloids tended to cover gossip and more salacious news to draw readers’ attention, they attracted criticism and disapproval from the colonial government and intellectuals, who frequently suppressed the production of these publications. Furthermore, tabloids were usually run by lean teams with high staff turnover, a problem compounded by insufficient professional training and a resulting inconsistency in quality. These internal structural weaknesses proved fatal in an increasingly competitive industry and ultimately led to the decline of the tabloid era. By the late 1950s, all tabloids in Singapore had ceased publication. It was not until Min Pao came along in the 1960s that this changed.

Legacy of tabloids

As periodicals for the people, tabloids provided spaces for diversity of expression. Their coverage encompassed voices from different segments of society, reflecting the concerns of the grassroots. These publications also nurtured writers of news, commentaries, and literary works, some of whom went on to become influential figures in the news and publishing industries. Tabloids bore witness to the evolution of popular culture and the complex realities of post-war Singaporean and Malaysian society. Although their popularity lasted just a few decades, tabloids captured the social momentum and cultural memories of their time, making them an important resource for understanding Chinese culture and social practices in pre-independence Singapore.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡独立前的华文小报. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | These terms are used in the printing industry to describe the size of a sheet of paper. A quarter-sheet is achieved by folding a full sheet of paper in half twice, while an eighth-sheet is achieved by folding it in half four times, and so on. |

| 2 | Tay Bon Hoi, Xinjiapo huawen baoye shi (1881–1972) [History of Chinese newspapers in Singapore (1881–1972)] (Singapore: Sima Publishers & Printers Co., 1973), 82. |

| 3 | Pang Nian Yin, Kaituo kongjian, jianrong bingxu: xinjiapo huawen xiaobao yanjiu (1925–1929) [Broadening space and taking everything in it: A study of Chinese tabloids in Singapore (1925–1929)] (PhD diss., National University of Singapore, 2013), 99. |

| 4 | Wang Gungwu, “Xinjiapo zaoqi huawen xiaobao yu zazhi” [Chinese tabloids and magazines in early Singapore], Nanyang Digest 14, no. 11 (1973), 740. |

| 5 | Choi Kwai Keong, Xinjiapo de huawen xiaobao yu zazhi [Chinese tabloids and magazines in Singapore], Singapore: Haitian wenhua qiye, 1993, 63. However, based on records in the British Museum, Wang Gungwu suggests that the number was 73. See Wang Gungwu, “Xinjiapo zaoqi huawen xiaobao yu zazhi” [Chinese tabloids and magazines in early Singapore], Nanyang Digest 14, no. 11 (1973): 740. |

| 6 | Yap Koon See, Maxin xinwen shi [The press in Malaysia and Singapore], Kuala Lumpur: Han Chiang School of Media & Communication, 1996, 116. Fang Jigen, Hu Wenying, Haiwai huawen baokan de lishi yu xianzhuang [The history and development of overseas Chinese newspapers], Beijing: Xinhua Publishing House, 64. |

| 7 | Tay Bon Hoi, Xinjiapo huawen baoye shi, Singapore: Xinma chuban yinshua gongsi, 1973,73. |

Choi, Kwai Keong. Yuanyuan liuchang: Shanghai shuju qishi zhounian jinian kanwu [A Long-standing Legacy: Shanghai Book Company 70th Anniversary]. Singapore: Shanghai Book Company, 1995. | |

Lee, Meiyu. “From Lat Pau to Zaobao: A History of Chinese Newspapers.” BiblioAsia 15, no. 4 (January–March 2020). | |

Pang, Nian Yin. Kaituo kongjian, jianrong bingxu: xinjiapo huawen xiaobao yanjiu (1925–1929) [Broadening space and taking everything in it: A study of Chinese tabloids in Singapore (1925–1929)]. PhD diss., National University of Singapore, 2013. | |

Tay, Bon Hoi. Xinjiapo huawen baoye shi (1881–1972) [History of Chinese newspapers in Singapore (1881–1972)]. Singapore: Sima Publishers & Printers Co., 1973. | |

Tay, Bon Hoi. “Xiaobao zhi wang zeng mengbi” [Zeng Mengbi, the tabloid king]. Lianhe Zaobao, 30 March 2019. | |

Wang, Gungwu. “Xinjiapo zaoqi huawen xiaobao yu zazhi” [Chinese tabloids and magazines in early Singapore]. Nanyang Digest 14, no. 11 (1973): 740–743. | |

Wong, Hong Teng. Zhanhou chuqi de xinjiapo huawen baokan (1945–1948) [Chinese newspapers in early post-war Singapore (1945–1948)]. Singapore: National University of Singapore Department of Chinese Studies, 1982. | |

Wong, Hong Teng. Xinjiapo huawen baokan shilunji [Essays on the history of Chinese newspapers in Singapore]. Singapore: Xin She, 1987. | |

Xie, Huai. Xinjiapo xiaobao shi [History of tabloids in Singapore]. Singapore: Ti Press, 1957. |