Singaporean Chinese hawker food: History and Evolution

From wanton mee to chicken rice, the evolution of Chinese hawker food in Singapore has been shaped by several factors: the socioeconomic backgrounds of immigrants on the island; their diverse races and dialect groups; as well as the difficulty of procuring certain ingredients that had traditionally been used in southern China.

Food of the working class

An often-overlooked feature of Singapore hawker food is that it is usually carbohydrate-heavy, with rice and noodles as the main base, and vegetables and meat playing secondary roles. A major reason is that the dietary habits of early Chinese immigrants in Singapore were shaped by necessity rather than indulgence.

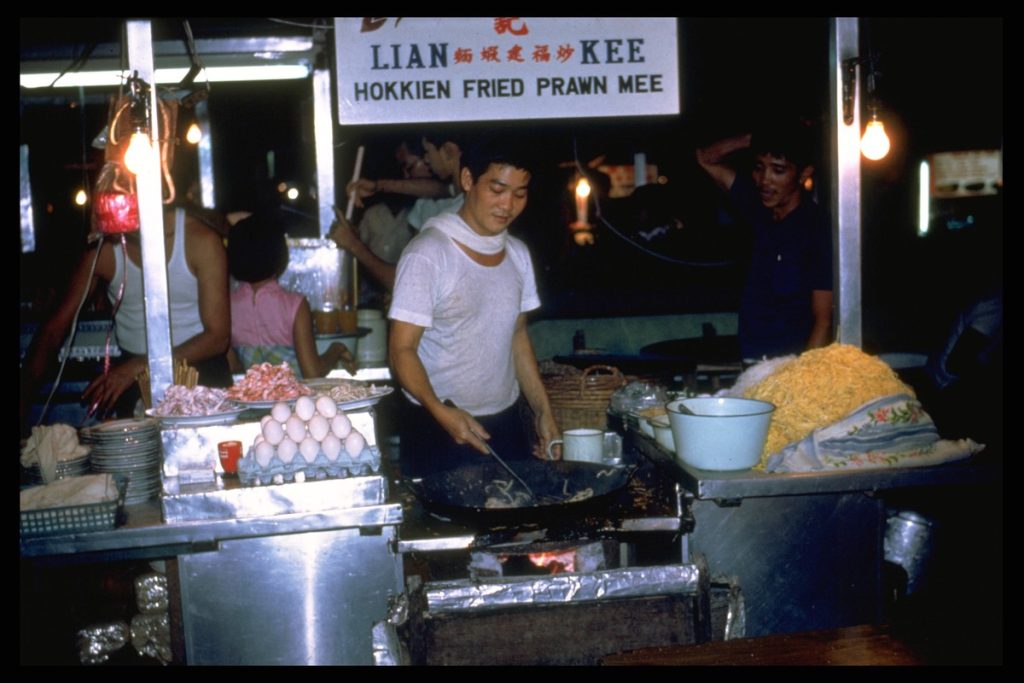

Most Chinese immigrants to Singapore during the colonial and pre-independence era (1819–1965) came from lower-class backgrounds and took on blue-collar jobs. For these labourer immigrants, food served purely a functional purpose — to provide the energy needed for physically demanding work. They ate to live, in sharp contrast to the modern Singaporean norm of living to eat.1 Street hawkers and eateries responded to this demand by offering dishes that were inexpensive and calorie-dense, serving cheap carbohydrate-based dishes that formed the bulk of street food. Popular rice-based dishes included Teochew porridge, cap cai png (economic rice), lor ah png (braised duck rice), and Cantonese roast meats (e.g. roast duck, char siew, pork belly) with rice. Similarly, noodle-based dishes such as char kway teow (fried kway teow), kway teow tng (flat rice noodles in pork broth), bak chor mee (dry minced meat noodles) or Singaporean fried Hokkien mee (fried egg noodles with lard) became common fare.

This preference for carbohydrate-heavy meals was not unique to Chinese immigrants but extended across other ethnic groups. Malay dishes such as mee soto (Malay noodle soup from Soto) or nasi padang (mixed rice from Padang) centred around noodles or rice, with secondary accompaniments of meat and vegetables. Similarly, Indian staples like nasi biryani (mixed rice with meat or vegetables) and roti prata (Indian flatbread) were based on basmati rice and flour. This early dependence on cheap, filling carbohydrates created a lasting dietary pattern and path dependency — one that continues to shape Singaporean hawker food today, where many popular dishes remain rooted in the same carb-heavy foundations established during Singapore’s formative years.

Immigration patterns and effects on demand and supply

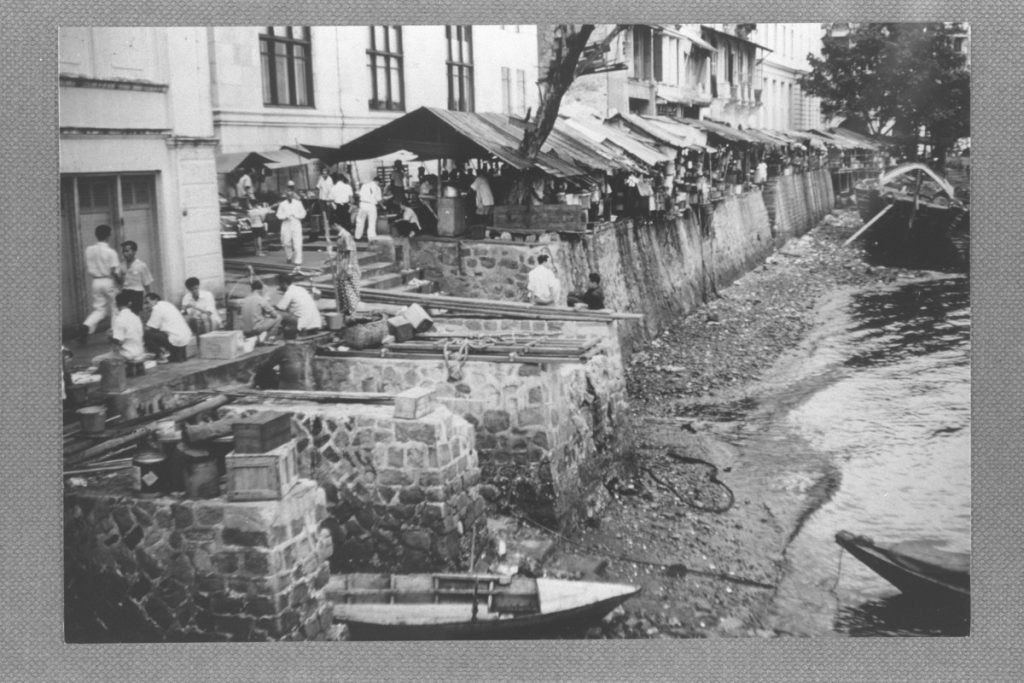

Immigration patterns have also significantly shaped the evolution of Singaporean Chinese hawker food, influencing both the supply of culinary expertise and the demand for specific dishes. Chinese migration to Singapore occurred in waves, with earlier arrivals establishing occupational niches that later immigrants had to navigate. The Hokkiens, Teochews, and Cantonese were among the first dialect groups to settle in Singapore, taking up manual labour jobs on plantations, at the docks, and for merchant houses.2 Their dominance in these industries was reinforced by clan associations, which facilitated the movement of labour within their dialect groups.

Dialect groups that arrived later, such as the Hainanese, and Henghua, had to occupy alternative sectors. The Hainanese, for example, were more likely to take up dong pou kang (domestic work in Hainanese), with many working as chefs or in the kitchens of British and Peranakan Chinese households. However, after World War II and the withdrawal of the British, many Hainanese cooks turned to the food and beverage industry for work, resulting in a disproportionate number of Hainanese chefs. As members of other dialect groups were less represented in cooking professions, Hainanese chefs came to dominate Chinese kitchens. They often prepared dishes outside their own culinary tradition, diluting the dialect-specific expertise typically preserved when communities cooked their own food.

At the same time, the increasing diversity within the Chinese population likely fuelled demand for broadly accessible Chinese dishes over dialect-specific ones. Hawkers who once specialised in dialect-specific fare had to adapt, prioritising accessibility over regional specificity, and likely offered dishes that appealed to a variety of dialect groups. Unlike in China, where they might have catered exclusively to their own dialect community, hawkers in Singapore needed to meet the broader culinary preferences of a more diverse customer base.

One manifestation of this shift is Singaporean Teochew porridge. Unlike traditional Teochew porridge restaurants in Chaoshan, which focus on Teochew-specific dishes, Teochew porridge eateries here offer a variety of dishes from different dialect groups. For instance, one can find Cantonese dishes like gu lou yok (sweet and sour pork), Hakka dishes like braised pork belly (braised pork belly with pickled mustard), and dialect-fluid dishes such as hae bee hiam (spicy dried shrimps) and kong bak (braised pork). As such, despite its name, Teochew porridge in Singapore is perhaps more accurately “Teochew-style porridge with an assortment of Chinese dishes”.

This evolution reflects the realities of catering to a multicultural customer base. Hawkers, in response to shifting demographics and consumer preferences, blended culinary influences from different Chinese dialects. In doing so, they helped shape a distinctly Singaporean style of Chinese cuisine — one rooted in tradition yet constantly adapting to the needs of its diverse patrons.

Ecological constraints

Lastly, Singapore’s ecological limitations have also played a crucial role in shaping its culinary landscape. Unlike southern China, where diverse seafood, game, and produce are readily available, Singapore’s limited natural resources necessitated substitutions and adaptations that have, over time, become defining features of local food.

For instance, the Malacca Strait — Singapore’s primary seafood source — harbours significantly less marine biodiversity than the Taiwan Strait. Studies indicate that the eastern coasts of Guangdong and Fujian, where Hokkiens and Teochews traditionally source their seafood, contain around 1,697 unique fish species. 3 In contrast, the Malacca Strait hosts only about 710 species, of which just 65% are commercially viable.4 Beyond seafood, key staples in Teochew cuisine, such as bamboo shoots and geese, were either not readily available or often too costly to procure in Singapore. These constraints forced early immigrants to adapt and localise their traditional dishes to their new surroundings.

Singapore’s hawker culture reflects a rich tapestry of historical, social, and ecological influences. From its origins as a bustling port to its evolution into a metropolitan city, hawker cuisine has been shaped by working-class immigrant diets, a need to cater to Singapore’s multicultural population, and adaptation to a scarcity of certain ingredients. Be it wanton mee, nasi padang, or roti prata, each dish is uniquely intertwined with facets of Singapore’s history and a testament to the tenacity of earlier generations.

| 1 | Wong Chiang Yin, How to Eat (Singapore: Focus Publishing, 2021), 62–67. |

| 2 | Lai Ah Eng, “The Kopitiam in Singapore: An Evolving Story about Migration and Cultural Diversity,” 7–8. |

| 3 | Chen Yong-Jun et al., “Research Review of Fish Species Diversity in Taiwan Strait,” ACTA HYDROBIOLOGICA SINICA 40, no. 1 (2016): 157–164. |

| 4 | A. G. Mazlan et al., “On the Current Status of Coastal Marine Biodiversity in Malaysia,” IJMS 34, no. 1 (March 2005): 79. |

Chen, Yong-Jun, Lin Long-Shan, Li Yuan, Zhang Jing, Song Pu-Qing, Zhang Ran, and Zhong Zhi-Hui. “Research Review of Fish Species Diversity in Taiwan Strait.” ACTA HYDROBIOLOGICA SINICA 40, no. 1 (25 January 2016): 157–164. | |

Lai, Ah Eng. “The Kopitiam in Singapore: An Evolving Story about Migration and Cultural Diversity.” Asia Research Institute Working Paper, no. 132 (2010): 1–29. | |

Mazlan, A. G., C. C. Zaidi, W. M. Wan-Lotfi, and B. H. R. Othman. “On the Current Status of Coastal Marine Biodiversity in Malaysia.” Indian Journal of Geo‑Marine Sciences 34, no. 1 (March 2005): 76–87. | |

Wong, Chiang Yin. How to Eat. Singapore: Focus Publishing, 2021. |