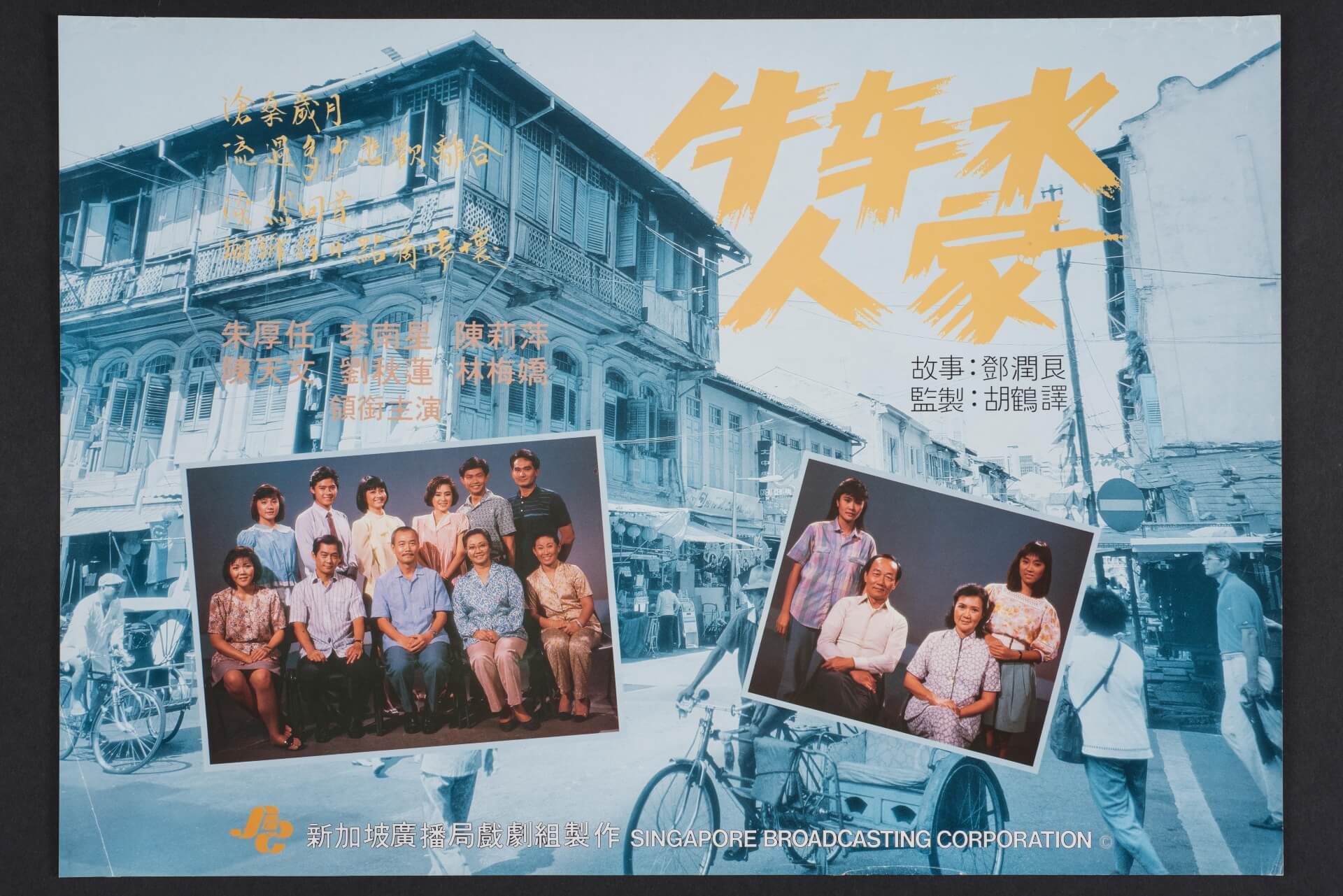

Wang Sha, Ye Feng and Their Legacy in Films

For those who grew up in Singapore before the 1990s, mentions of Wang Sha (1925–1998) and Ye Feng (1932–1995) would likely evoke memories of the comedic duo’s getai (stage), radio, or television performances. Lesser known, however, is their active participation in cinema in the 1970s and 1980s.

Localised films

Between the two, it was Wang who first made the leap onto the big screen in Door of Prosperity (1959). The multi-dialect romance film, directed by Hsu Chiao Meng (1910–1995), took the then newly-opened Nanyang University as its backdrop and starred several local Chinese-language performers. It opened during National Loyalty Week (3–9 December 1959), signalling the team’s commitment to Singapore’s anti-colonial nationalisation and localisation movements.

Later, Wang continued to play a part in the making of such “localised Chinese-language films”. My Love in Malaya (1963), a film shot entirely in Singapore, featured a largely local cast and was produced by Singaporean sisters Chang Lye Lye and Landi Chang. Wang played the role of the main lead’s father, who was also a satay man.

Breaking into Hong Kong

While Wang had an early start in film acting, neither he nor Ye established themselves as full-fledged film performers before the 1970s. It was their participation in Hong Kong’s media industry during the mid-1970s that really kickstarted the duo’s film acting career. In 1974, Ye had his first taste of acting for film in The Nutty Crook (1975), produced by veteran Hong Kong director John Lomar’s film company. Although The Nutty Crook would only be released retrospectively after Ye gained fame for his role in his next film, this experience gave him an inroad into Hong Kong’s film industry.

The next film project that would land on Wang and Ye’s laps was the first of the popular Crazy Bumpkins series: The Crazy Bumpkins (1974). It was also directed by John Lomar, but produced by the Shaw Brothers (Hong Kong) Company. This was the first film that featured both of them together, and the duo impressed audiences with their adept comedic performances and impeccable chemistry. The roaring success of The Crazy Bumpkins affirmed both Wang and Ye’s potential as film actors, paving the way for their gradual move to cinema and, consequently, to Hong Kong.

That being said, the duo’s leap into cinema can, in fact, be traced further back to their first appearance on a Hong Kong TV variety show. Perhaps the single most pivotal event which facilitated the duo’s transition into cinema was their signing on to Hong Kong’s Television Broadcast Limited Company (TVB), which was owned by the Shaw Brothers (HK), through the mediation of Singaporean TV producer Robert Chua Wah Peng.

In the late 1960s, Chua left Singapore’s television industry for Hong Kong to join TVB. Upon arriving in Hong Kong, the producer spent five months observing the local life and culture of Hong Kongers to create the variety show Enjoy Yourself Tonight. The show grew to become hugely popular and in the 1970s, Chua invited Wang and Ye to perform on it. The duo’s act was tremendously well-received, proving that their brand of humour had struck a chord with the people of Hong Kong.

Soon after, TVB officially signed on with the duo, formally marking the beginning of their television and film career in Hong Kong. Wang later became contracted to the Shaw Brothers (HK), and Ye to John Lomar’s film company. Despite signing on to different film companies, Ye continued to act alongside Wang in many Shaw Brothers (HK) productions, including the aforementioned Crazy Bumpkins. This was made possible by special “loan-out” agreements between Lomar’s film company and the Shaws, who believed that even in cinema, Wang and Ye yielded the best results when performing together.

The fact that Wang and Ye’s film-acting endeavours began in Hong Kong (despite being originally based in Singapore) was partly due to industrial realities at that time. Following the closure of major Singapore film studios in the 1960s and early 1970s, coupled with transformative socio-political changes, Singapore had ceased to be a filmmaking centre. Indeed, the 1970s and 1980s were a time in Singapore’s film history when feature filmmaking activity decreased and eventually stopped. This explains why Hong Kong — then a robust media capital in the region — was where the two established their grounds as film actors. More importantly, with this move to Hong Kong, Wang and Ye effectively became among the earliest Singaporean pioneers in Chinese-language media to achieve transnational stardom as film stars in the post-studio era (i.e. the post-1960s).

In total, Wang and Ye acted in approximately 40 films, most of which were shot and produced in Hong Kong. Some of their most popular films include: the popular Crazy Bumpkins series (1974–1976), the Mr Funnybone series (1976 and 1978), and the Mad Monk series (1977 and 1978). The duo stayed in Hong Kong for nearly a decade, with Wang returning to Singapore before Ye after about seven years because he found it harder to adapt to life in Hong Kong, particularly its subtropical climate. Thereafter, Wang did a short stint in Taiwan’s entertainment industry, acting in a few more films that were shot and produced there, including Three Money Hunters (1980).

Comic relief

Overall, Wang and Ye’s film performances often fulfilled the role of comic relief. Besides being a narrative device that relieves emotional tension in heavy dramas, the meaning of comic relief here also refers to a way to soothe the everyday tension of the everyman living in the fast-changing societies of 1970s and 1980s Singapore and Hong Kong through humour. This was a time when both governments pursued aggressive economic policies, turning the cities into two of the fastest-developing capitalist economies within a short span of time. Accompanying this fast and enormous economic growth was the rapid improvement in standards of living, as well as the growth of a collective mindset that was increasingly consumerist and materialistic.

In this context, the characters played by Wang and Ye in these entertaining films provided much-needed moments of respite for both their Singapore and Hong Kong audiences, who were wrestling with the intensifying pace of life in rapidly developing capitalist societies. Their comedic acts often gave familiar everyday scenarios a slapstick or comedic treatment, enabling audiences to laugh at themselves and offering a sense of catharsis. Coupled with the distance afforded by cinema, Wang and Ye’s film characters provided audiences with a temporary avenue through which to laugh and make light of stressful everyday situations, and poke fun at themselves.

Su, Zhangkai. Agak-agak: 90 stories of Wang Sha and Ye Feng. Singapore: Singapore Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan, 2019. | |

Yeo, Min Hui. Programme booklet for Comic Relief: Film Retrospective and Exhibition on Wang Sha and Ye Feng. Singapore: Asian Film Archive, 2024. |