Chinese and South Asian religious encounters in Singapore

Singapore, like much of Southeast Asia, has long been a crossroads for trading and migrant communities, linking East and South Asia. Migrants arriving via the Strait of Malacca and the South China Sea brought with them their deities, rituals, and belief systems, which took root and evolved in a new environment. As a key entrepôt, Singapore — as well as Malacca and Penang in the Straits Settlements — became a focal point for religious and cultural interaction. The region’s commercial ties with communities across the Strait of Malacca facilitated exchanges among Chinese religious practitioners, Hindu devotees, and itinerant merchants and ritual specialists from South Asia. These enduring connections continue to shape Singapore’s religious landscape today.

South Asian religious transmission and migrant networks in Southeast Asia

Like Chinese religious traditions, the precise period and mechanisms by which Hindu beliefs and rituals became embedded in Singapore and the broader Nusantara remain uncertain. The presence of Hindu elements from the 5th century in the Bujang Valley suggests that Hindu-Buddhist traditions were transmitted through an entrepôt complex, where religious practices were integrated into trade networks connecting key Buddhist centres in southern Thailand and the Malay Peninsula.1 During the Chola empire (c. 9th–13th centuries), Singapore was situated within a broader network of Tamil maritime trade and cultural exchange. The founder of Singapore, Sang Nila Utama of Palembang (fl. 13th century), as recorded in the Sejarah Melayu, was likely of Hindu orientation. His title, Sri Tri Buana, meaning “Lord of the Three Worlds”, was in Sanskrit, the working language of Hindu-Buddhist polities at the time, reflecting the deep entanglement of Hindu-Buddhist influence in early maritime polities.2

Early encounters between Chinese religious traditions and Hinduism

Historically, Chinese religious traditions and Hinduism have shared significant overlaps, shaped by centuries of cultural and religious exchange and mediated partly through the spread of Buddhism to East Asia. Buddhist deities and scriptures reflect Indian influences, while Taoist traditions incorporate stellar deities that parallel Hindu cosmology. The Nine Bright Sovereigns, invoked in Dipper Worship ceremonies, have counterparts in the Hindu Navagraha, a connection facilitated by long-standing exchanges along the Silk Road since the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), with greater intensity from the Tang dynasty (618–907) onwards, alongside the spread of Buddhism. 3 Even today, Hindu temples in Singapore — predominantly of the Saivite4 tradition — enshrine the nine planetary deities, whom both Hindu and Chinese devotees circumambulate nine times as part of their worship, reflecting the continued interweaving of cosmological beliefs across religious traditions.

Large-scale migration in the late 18th and 19th centuries brought credit-ticket labourers from China and labourers from India, alongside merchants, traders, convict labourers, and refugees fleeing political upheaval and natural disasters. As a key port of transit, Singapore connected flows of wealth, people, and ideas in South Asia, the Middle East, and East Asia. In response, a growing number of migrant associations emerged, serving not only as religious hubs but also as community centres providing charity and support. Hinduism, like Chinese religious traditions, was initially transplanted through grassroots practices, dominated by the veneration of village deities such as Kaval Deivam, whose shrines and temples often incorporated spirit-mediumship, dream revelations, and other forms of practical devotion.5 These expressions of faith, deeply rooted in the lived experiences of migrant communities, resonated most strongly with working-class migrants, offering spiritual guidance, protection, healing, and — most importantly — a shared sense of home in unfamiliar surroundings.

Interfaith interaction and shared sacred spaces

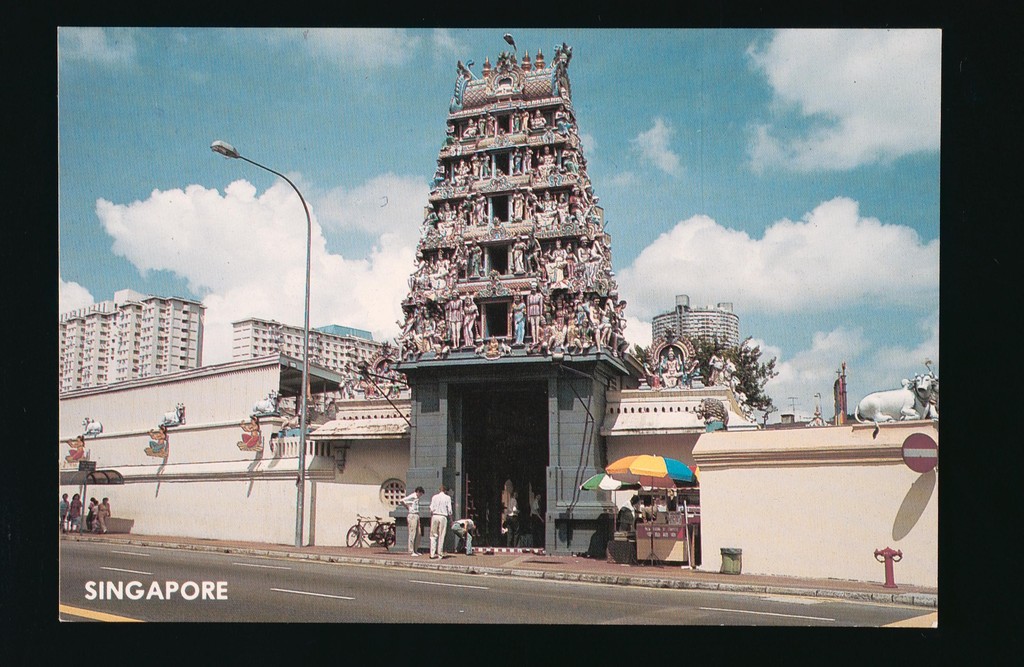

Singapore’s early religious landscape was shaped by both structured urban planning and organic cultural interactions. While the Raffles Town Plan (1822) sought to impose zoning along ethnic lines — dividing the city into enclaves for the Chinese, Indians, Malays, and Europeans — religious institutions continued to reflect the interwoven lives of different communities.6The Sri Mariamman Temple, Singapore’s oldest Hindu temple, was established in 1827 by Naraina Pillai (fl. 1819) on South Bridge Road. Though situated within what became a predominantly Cantonese community — Kreta Ayer, more commonly known as Chinatown — the temple remained a focal point for Hindu worship. The adjacent Pagoda Street, named after the temple’s gopuram (tower), attests to its enduring presence.7

Nearby, the Sri Layan Sithi Vinayagar Temple at the end of Keong Siak Road, founded in 1917 and relocated in 1920 under Chettiar8leadership, further illustrates how Hindus and Chinese not only lived in proximity but also shared everyday spaces, fostering ongoing religious and cultural exchanges. Similarly, the Sri Thendayuthapani Temple, built in 1859 by the Chettiar community at Tank Road (neighbouring the Teochew community’s Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan) reflects their economic dominance and religious contributions. As a mercantile diaspora that controlled capital investment and moneylending in the absence of formal banks, the Chettiars played a leading role in temple-building, which closely followed the geography of their trade networks.9

The Nagore Dargah Shrine (built c. 1828–1830), now the Nagore Dargah Indian Muslim Heritage Centre, was constructed beside Thian Hock Keng (1821–1822), one of Singapore’s most prominent Chinese temples, by Chulia traders from the Coromandel Coast. Though dedicated to Shahul Hamid of Nagore (1504–1570), an Islamic holy man, the shrine was part of a shared religious landscape that fostered interethnic encounters.10

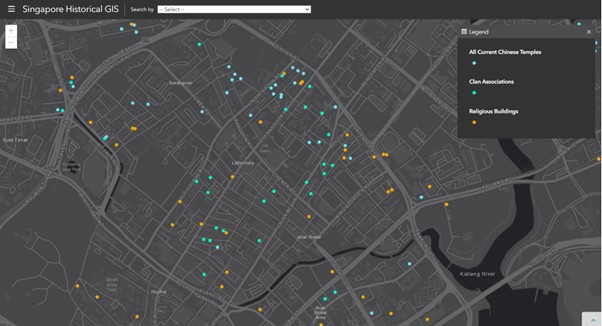

The location of these established Indian temples within the Central Business District underscores Singapore’s broader history of religious pluralism, where Hindu, Chinese, Christian, and Islamic places of worship stood side by side.11However, intercultural and interethnic encounters were not confined to the city centre. The region known as Kampong Kapor — what would later become integrated into the space known as Little India — was also home to numerous Chinese religious associations and temples. This serves as evidence that boundaries do not isolate communities but instead create spaces for inter-cultural exchange.

Everyday religious interactions: Deities, shrines, and festivals

The fluid incorporation of Chinese and Hindu deities into everyday religiosity in Singapore is evident across numerous temples and shrines. The veneration of Muneeswaran — a deity popular among the Tamil Hindu diaspora — often occurs alongside that of the Chinese earth deity, Tua Pek Kong. At Hock Huat Keng, for instance, Muneeswaran is enshrined in the same sanctum as Tua Pek Kong, reflecting shared understandings of protection and territorial guardianship. Similarly, Ganesha enjoys widespread veneration in Chinese temples, such as Jiutiao Qiao Na Du Gong Temple in Tampines and Tien Sen Tua in Paya Lebar. At Loyang Tua Pek Kong Temple, an entire sanctum is dedicated to Ganesha, alongside Durga and other Hindu goddesses.12 This intermingling extends to roadside shrines, where images of Ganesha frequently appear alongside Chinese deities. Conversely, some Hindu temples also enshrine Chinese deities — Waterloo Street’s Sri Krishnan Temple venerates Guan Yin, while the Holy Tree Sri Balasubramaniar Temple houses an image of Siddhartha Gautama (fl. 5th–6th centuries BCE). At Sree Ramar Temple in Changi Village, a standing image of Amitābha reflects these ongoing cross-religious exchanges.

Urban planning in post-independence Singapore further facilitated such interactions. Religious centres were relocated and established within new housing estates, designed to accommodate the nation’s main faiths while providing shared religious amenities. Each residential estate was planned to include a diverse representation of religious sites, ensuring accessibility for different communities and fostering continued interfaith interactions.13 In Sengkang, for instance, the Combined Temple — housing Chong Ghee Temple and Ban Kang Thian Hou Keng, a century-old Mazu temple originally founded in the coastal settlement of Kampong Sungai Tengah and later relocated to Pulau Ubin in the 1980s before returning to Sengkang after the millennium — stands adjacent to the Arulmigu Velmurugan Gnanamuneeswarar Temple (originally from Serangoon Road, before relocating in the early 2000s).14 This spatial relationship mirrors that of Kwan Im Thong Hood Cho Temple and Sri Krishnan Temple on Waterloo Street. Many Chinese devotees, regardless of their primary religious affiliation, continue to visit neighbouring temples with offerings of incense in a shared spirit of devotion.15 Even today, it is not uncommon for Chinese and Indian devotees from these historic sites to visit one another’s places of worship — a testament to the enduring, if unspoken, bonds forged through shared spaces and coexistence.

These interactions extend beyond static worship spaces. Yew keng by Chinese religious institutions — processions in which Chinese deities are carried in palanquins to bless surrounding territories — frequently include visits to Hindu temples. One notable example is the annual procession conducted by Jia Zhui Kang Dou Mu Gong Feng Shan Si. As part of the Nine Emperor Gods Festival celebrations, the temple’s procession on the sixth night of the ninth lunar month stops en route at Sree Maha Mariamman Temple and Holy Tree Sri Balasubramaniar Temple, where the Nine Emperor Gods’ palanquin are greeted with a lamp offering in the temple’s sanctum, and the temple’s leadership is welcomed with floral offerings — reinforcing longstanding ritual exchanges between both traditions.16

Festivals also provide key moments for interfaith engagement. The Nine Emperor Gods Festival and Navaratri (Nine Nights) — also known as Durga Puja and Dussehra (marking Rama’s victory over Ravana on the 10th day) — are celebrated by both Chinese and Hindu communities.17These festivals often overlap in the ritual calendar, sharing similar thematic elements. Local academic Vineeta Sinha’s fieldwork highlights how Hindu festivals in Singapore frequently adopt the logistical forms of Chinese religious celebrations, such as the use of large, tented structures in Housing and Development Board (HDB) estates.18 At Yishun’s Huang Mu Gong, homa fire rituals feature alongside spirit-mediums assuming the forms of Hindu goddesses, alongside deities familiar to the Chinese pantheon. These practices were clearly evidence of their reinterpretation, and recontextualised within a “Taoist liturgical framework”, allowing deities to be incorporated into Chinese ritual structures.19

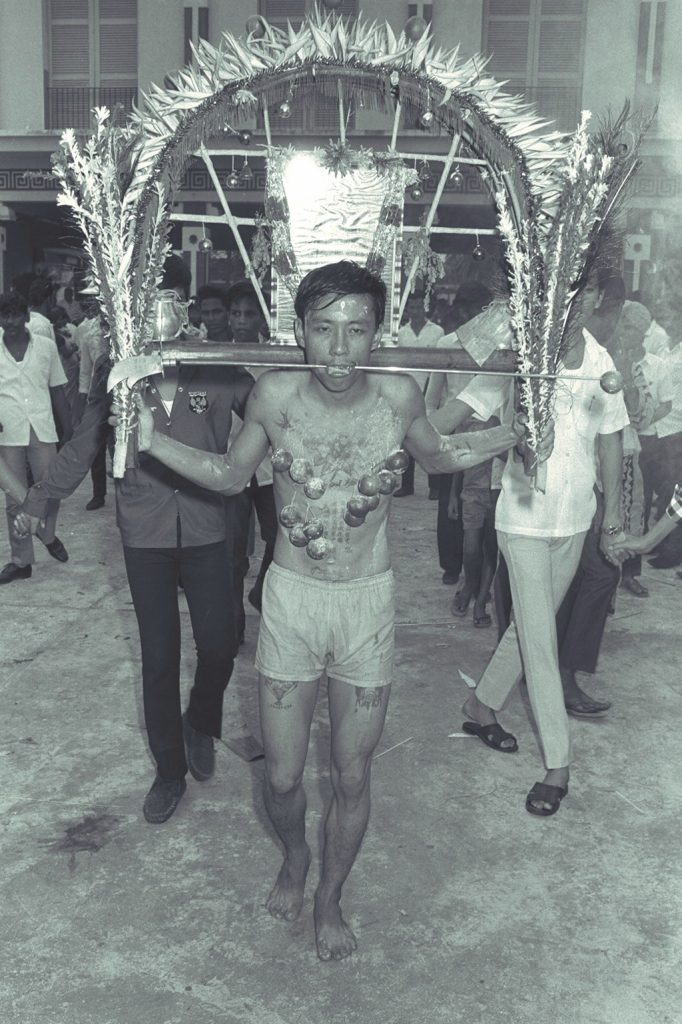

This ongoing exchange is further reflected in contemporary religious participation. The increasing presence of Chinese devotees at Thaipusam and fire-walking ceremonies (Thimithi), for instance, signals that interreligious interactions in Singapore remain dynamic and evolving.20Far from being a relic of the past, the interwoven religious landscape of Chinese and Hindu traditions continues to shape Singapore’s spiritual and cultural fabric today.

| 1 | Stephen A. Murphy, “Revisiting the Bujang Valley: A Southeast Asian Entrepôt Complex on the Maritime Trade Route,” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society 28, no. 2 (2018): 355–389. |

| 2 | John N. Miksic, Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea, 1300–1800 (Singapore: NUS Press, 2013), 145–151. |

| 3 | Jeffrey Kotyk, “Astrological Iconography of Planetary Deities in Tang China: Near Eastern and Indian Icons in Chinese Buddhism,” Journal of Chinese Buddhist Studies 30 (2017): 33–88. |

| 4 | One of the prominent branches of contemporary Hinduism, which holds Shiva as the supreme figure of worship. |

| 5 | Vineeta Sinha, “Unravelling ‘Singaporean Hinduism’: Seeing the Pluralism Within,” International Journal of Hindu Studies 14, no. 2/3 (December 2010): 271–272. |

| 6 | This was brought to the author’s attention by Koh Keng We in 2016. |

| 7 | See E. Sanmugam et al., eds., Sacred Sanctuary: The Sri Mariamman Temple (Singapore: Sri Mariamman Temple, 2009). |

| 8 | The Chettiars are a subgroup of the Tamil community from Chettinad in Tamil Nadu, India, and are most commonly associated with the moneylending profession. See Jaime Koh, “Chettiars,” Singapore Infopedia. |

| 9 | Hans-Dieter Evers and Jayarani Pavadarayan, “Religious Fervour and Economic Success: The Chettiars of Singapore,” in Indian Communities in Southeast Asia, edited by K. S. Sandhu and A. Mani (Singapore: ISEAS Publishing, 1993), 847–865. |

| 10 | Melody Zaccheus, “Indian-Muslim Centre to Reopen Next Month,” The Straits Times, 23 October 2014. |

| 11 | Several of these institutions’ intertwined histories can be consulted, visited, and experienced through in-person visits, as documented and laid out in a set of heritage trails developed by the Singapore National Heritage Board. |

| 12 | Siri Rama, “The Dance of the Elephant-Headed God: Ganesha in Buddhist Temples of Southeast Asia,” paper presented at Chinese Temples in Southeast Asia, 28 February–1 March 2019, organised by Asia Research Institute, National University of Singapore. |

| 13 | Lily Kong and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, The Politics of Landscapes in Singapore: Constructions of “Nation” (New York: Syracuse University Press, 2003), 79, 88. |

| 14 | On the Combined/United Temple phenomena, see Hue Guan Thye, “The Evolution of the Singapore United Temple: The Transformation of Chinese Temples in the Chinese Southern Diaspora,” Chinese Southern Diaspora Studies 5 (2011–2012): 157–174. |

| 15 | Tommy Koh, “Miracle on Waterloo Street: A Jewish Synagogue, a Hindu Temple and a Buddhist Temple Are Clustered on This Street. Singapore’s Religious Harmony Has Come About as a Result of Conscious Policy, Laws and Institutions,” The Straits Times, 21 February 2015. Also see Daniel P. S. Goh, “In Place of Ritual: Global City, Sacred Space, and the Guanyin Temple in Singapore,” in Handbook of Religion and the Asian City: Aspiration and Urbanization in the Twenty-First Century, edited by Peter van der Veer (Oakland: University of California Press, 2015), 21–22. |

| 16 | Koh Keng We et al., The Nine Emperor Gods Festival in Singapore: Heritage, Culture and Community, vol. 2A (Singapore: Nine Emperor Gods Project, Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, 2023), 373–375. |

| 17 | Ibid, and Pranav Venkat, Tejala Niketan Rao, and Esmond Soh, “The Durga Puja among the Bengalis in Singapore: History, Tradition and Ritual,” Singapore Heritage Festival Photo Essay, last updated 13 June 2020. |

| 18 | Vineeta Sinha, “‘Bringing Back the Old Ways’: Enacting a Goddess Festival in Urban Singapore,” Material Religion 10:1 (2014): 76–103. |

| 19 | Fangterrence Photographer, “Yi shun Huang mu gong | zhong shenming gan bang raoxing | guimao nian” [Yishun Huang Mu Gong | Procession of Deities in the Kampong | Year of the Water Rabbit], YouTube video, 10 December 2023. The quotation is from Kenneth Dean, Taoist Ritual and Popular Cults of Southeast China (New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1993), 3. |

| 20 | Brian Teo, “Two S’pore Friends of Different Faiths, One Thaipusam Walk of Devotion,” The Straits Times, 12 February 2025. |

Goh, Daniel P. S. “Chinese Religion and the Challenge of Modernity in Malaysia and Singapore: Syncretism, Hybridisation and Transfiguration.” Asian Journal of Social Science 37, no. 1 (2009): 107–137. | |

Lim, Keak Cheng. “Traditional Religious Beliefs, Emigration and the Social Structure of the Chinese in Singapore.” In A General History of the Chinese in Singapore, edited by Kwa Chong Guan and Kua Bak Lim, 479–500. Singapore: Nanyang Technological University and Singapore Federation of Chinese Clan Associations, 2019. | |

Lim, Khek Gee Francis, Kuah Khun Eng, and Lin Chia Tsun. Chinese Vernacular Shrines in Singapore. Singapore: Pagesetters Services, 2023. | |

Sinha, Vineeta. “‘Mixing and Matching’: The Shape of Everyday Hindu Religiosity in Singapore.” Asian Journal of Social Science 37, no. 1 (2009): 83–106. | |

Sinha, Vineeta. “‘Hinduism’ and ‘Taoism’ in Singapore: Seeing Points of Convergence.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 39, no. 1 (2008): 123–147. | |

Sinha, Vineeta. “Unravelling ‘Singaporean Hinduism’: Seeing the Pluralism Within.” International Journal of Hindu Studies 14, no. 2/3 (December 2010): 253–279. | |

Wee, Vivienne. Religion and Ritual Among the Chinese of Singapore: An Ethnographic Study. Master of Social Sciences Thesis, University of Singapore, 1977. |