Northern lion dance

The lion dance is a martial arts performance with a history spanning over 1,500 years. It dates back to the Northern Wei dynasty (386–533), when a performer from the Hu ethnic group introduced a mesmerising dance to the imperial court using a wooden lion’s head mask. The emperor was so impressed that he declared it the Northern Wei Auspicious Lion. By the Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), this dance was widely recognised as northern lion (beishi) dance and often performed at festivals.1 The southern lion dance (nanshi or xingshi) style emerged much later in China’s Guangdong province, evolving into its own unique tradition.

The northern lion dance, which typically has two dancers per lion, features a fur-covered costume and is more lifelike than the southern style. The head and body of the lion are seamlessly connected, giving the dance a strikingly realistic look. In contrast to their southern counterparts, which are known for their more aggressive stances and their plucking of greens (caiqing), the northern lions are gentler and more playful, often appearing tamer. In Singapore, northern lions are preferred for gala dinners and events welcoming dignitaries, while southern lions are more popular during Chinese New Year and the opening of new businesses.

The evolution of lion dance in Singapore is deeply intertwined with the social and cultural fabric of the island. In its early days in Singapore, lion dance, along with other traditional Chinese arts, was primarily practised within clan associations established to serve as support networks for new immigrants. Another organisation breathing life into the art form was Chin Woo Athletic Association, a martial arts organisation founded in Shanghai in the early 20th century. In 1921, it set up a branch in Singapore, which remains active to this day.2

Chin Woo Athletic Association and the Birth of the Golden Lion

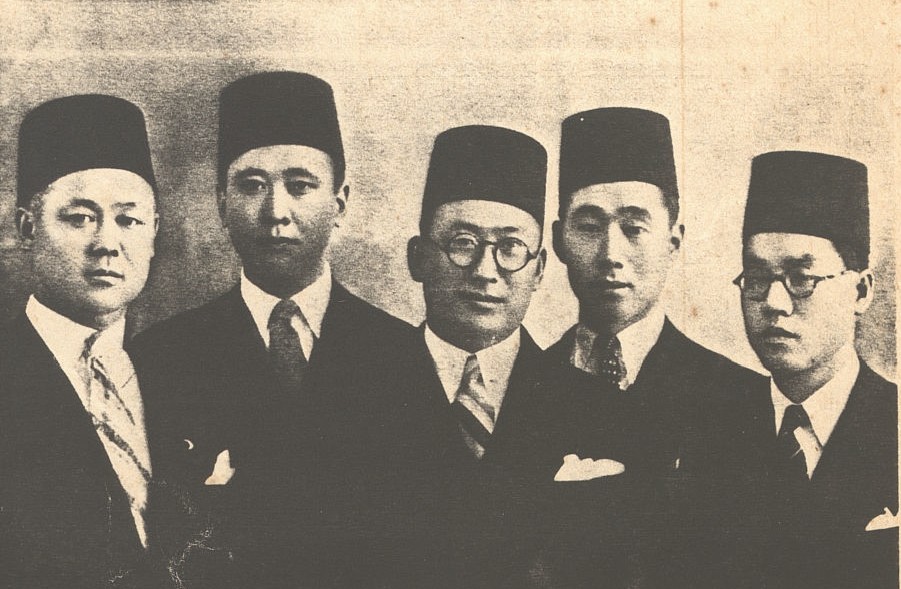

Chin Woo Athletic Association, which started out as a sports school, was notable for its promotion of northern lion dance, a rather rare sight in Singapore due to the challenges of training and performance requirements. In 1934, pioneer martial arts instructor Wei Yuan Feng (1906 – 1984) brought the very first batch of northern lions to the association in Singapore. Unfortunately, they were destroyed during the Japanese Occupation (1942–1945).

In its early days in Singapore in the 1930s, the northern lion dance posed significant challenges. The first lion heads used by Chin Woo were made from dense yellow clay and accompanied by a cape crafted from green hemp. Weighing around 10kg, these heavy lion costumes made the performers’ movements clumsy, and they lacked the agility that the dance later became known for. The performers needed to be strong and muscular just to handle the weight, but even then, their movements were limited, preventing the dance from achieving its full deft potential. As a result, the northern lion dance struggled to gain popularity in its early years.

In 1945, to revive this traditional art form, Wei Yuan Feng ordered a pair of lions from the Shanghai Chin Woo Association. However, when the lions finally arrived in 1953, they were still extremely heavy and just as difficult to manoeuvre. After multiple attempts to perform with these lions, it became obvious that they were too uncomfortable to dance with. As a result, Wei decided to donate them to Nanyang University (merged with University of Singapore in 1980 to form National University of Singapore), where they would be preserved and displayed as part of a cultural heritage collection.

Undeterred by this setback, Wei partnered with Fang You Chang (1904–1972), another martial arts instructor, to reimagine the northern lion. They moved away from using heavy materials like mud and sand and instead crafted the lion’s head from lightweight bamboo strips. The heads were then adorned with golden paper and wool dyed a vibrant golden yellow, while the cape was made from Luzon hemp, also dyed the same colour. After continuous refinements, they reduced the lion’s head weight to just 3 to 3.5kg, with the cape weighing about 2 to 2.5kg, making the lion 5kg lighter than its predecessor. This transformation enabled the dancers to bring the Golden Lion, as their creation was dubbed, to life on stage.

From the 1960s through the 1980s and even into the 2000s, members of Chin Woo have collaborated to improve the presentation of the lion. Initially, lion heads were adorned in colours like pink and yellow, but these designs did not have the appeal they were aiming for. So, they decided to enhance the lion heads with shiny gold paper, giving birth to the Golden Lion. In the 1960s, the lion had a fiercer appearance, but by the 1970s, they made adjustments to create a gentler, more approachable look.

Influence of Peking opera

In 1960, the Chin Woo Athletic Association in Singapore took a major step by forming a Peking opera troupe and inviting Liu Fu Shan (1903–1973), an accomplished Peking opera teacher from Tianjin, as an instructor. Under his expert guidance, the troupe seamlessly blended the techniques of the Golden Lion Dance with the theatrical elements of Peking opera. This innovative combination, enhanced by the rhythmic beats of gongs, drums, and the distinctive sound of the suona, brought the performance to a new level. The Golden Lion Dance became a cultural symbol, and its significance was cemented in 1976 when its image was prominently featured on the S$10 note issued by the Monetary Authority of Singapore, highlighting its lasting impact on the nation’s heritage. In 1972, the Golden Lions performed at Edinburgh Castle. It had the honour of welcoming and greeting the Queen Elizabeth II (1926–2022) in her visits to Singapore in 1972, 1989 and 2006. The Golden Lions were also in high demand during prestigious international events, such as Singapore Airlines’ inauguration of new flight routes.

Unique style and performance dynamics

What distinguishes the Golden Lion Dance is its unique style and performance dynamics unlike other lion dance variations is the lion’s interaction with a wushi or warrior who taunts the lion with a xiuqiu — a colourful, auspicious ball with a rattan frame and decorated with bells and ribbons. This ball is said to symbolise the sun and represent the balance of cosmic forces. The shape embodies the dual powers of nature — creation and destruction, light and darkness.3 The lion, mesmerised by the xiuqiu as it moves skilfully in the warrior’s hands, follows it with a playful, almost childlike enthusiasm, bringing the lion’s lively personality to life. As it chases the xiuqiu, the lion takes on a series of challenging moves that showcase the performers’ remarkable skill and precision. It may leap onto a high platform, carefully tread across a suspended plank while balancing on a large ball, or execute impressive jumps, even rising to stand on its hind legs in pursuit of this elusive xiuqiu.

Amplifying the performance, the warrior’s acrobatics — flawless somersaults and agile handling of the xiuqiu — create a spirited and engaging interaction with the lion.

Usually seen as a pair, the male lion has an ang cai or red silk pompom on his head, while his female counterpart has a green silk pompom. The origins of these “pom pom” balls may trace back to Hai Lung – the most cherished Pekingese of Empress Cixi (1835–1908). Hai Lung was adorned with two fluffy pom poms behind his ears — one crafted from red silk and the other from green. Northern lions bear a striking resemblance to Pekingese dogs or guardian lions (also known as foo dogs).

During a performance, Chin Woo’s Golden Lions — which have sleek, straight coats of fur — expertly mimic the playful, protective, and at times fierce behaviour of the lion, making it seem as though a living creature is on stage. The lions are sometimes portrayed as a family, with two large “adult” lions accompanied by smaller “young” lions, creating a charming display of familial bonds.

Changing with the times

Public perception of lion dance in Singapore has changed over the years. By the 1960s, both northern and southern forms of lion dance had developed a somewhat negative reputation due to its associations with certain street gangs. However, entertainment options were limited at the time, and some youths gravitated towards lion dance as a form of self-expression. To revitalise the art form, lion dance troupes began to modernise. They introduced competitions, showcasing the physical skill and martial arts elements of the dance, to attract younger participants and show that the art form had evolved beyond its troubled past. The Ngee Ann City National Lion Dance Championships, held annually on Orchard Road since 1995, became a major milestone in the reinvention of the art form. The public event, which features the southern lion dance, combining dramatic performances and impressive acrobatics, helped to make lion dance a source of athletic and cultural pride.

Chin Woo Athletic Association’s golden lion troupe can be seen performing at public events such as Chinatown’s Five Footway Festival, Singapore Heritage Festival and Qixi Festival. The association has also embraced social media to increase awareness and foster appreciation for the rare Golden Lion dance.

Another troupe to note for its Northern Lions is Wenyang Sports Association (Singapore), established in 2004. Wenyang began training in this art form at the start of 2006. Their Drunkard Northern Lion Dance routine earned them the 13th Ngee Ann City National Lion Dance Championships title in 2007, a massive achievement for a young troupe at that time. Wenyang also earned champion titles for their Northern Lion dance routines in 2006, 2010, 2011 in Singapore and first runner-up titles in Shanghai and Jiangxi’s Jiujiang in China. What is also unique to Wenyang is a pair of Snow Northern Lions, being pure white in colour with silver faces — the only pair in Singapore. The Snow Northern lion dance routine is carefully orchestrated to the rhythm of a well-known Chinese song, Haohan ge (Song of the Brave Warriors). This dance choreography received widespread praise from the public during their performance at the Ngee Ann City National Lion Dance Championships in 2019.

Today, northern lion dance continues to thrive in Singapore as both a respected tradition and a vibrant, modern form of performance art.

| 1 | Marianne Hulsbosch, Elizabeth Bedford and Martha Chaiklin, Asian Material Culture (Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2009), 112. |

| 2 | Chin Woo Athletic Association was founded in Shanghai in the early 20th century. In 1919, it set up a branch in Canton (present-day Guangzhou) whose opening ceremony was graced by renowned martial arts master Wong Fei-hung (1847–1925). The association went on to set up more than 80 branches in over 30 countries, including Singapore. |

| 3 | C.A.S. Williams, Outlines of Chinese Symbolism and Art Motives: An Alphabetical Compendium of Antique Legends and Beliefs, as Reflected in the Manners and Customs of the Chinese (New York: Dover Publications, 1976), 253–254. |

Godden, Rumer. The Butterfly Lions: The Story of the Pekingese in History, Legend, and Art. London: Macmillan, 1977. | |

Pee, Stephanie. “History of the Golden Lion in Singapore”. BiblioAsia, online exclusive, March 2025. | |

Seow, Peck Ngiam. “One Hundred Years of Martial Arts: A History of the Singapore Chin Woo (Athletic) Association”. BiblioAsia 20, no. 1, April–June 2024. | |

Singapore Wushu Dragon & Lion Dance Federation. “Northen Lion Characteristics”. | |

Xinjiapo Heshan huiguan qingzhu yinxi ji huzhubu qi zhounian jinian tekan [Commemorative publication celebrating Hok San Association (Singapore)’s silver jubilee and the 70th anniversary of the mutual-aid department]. Singapore: Hok San Association, 1965. |