A brief history of seal carving in Singapore

A seal (in the simplest and most general terms) is a piece of material, often stone, on which an identifier, often a name or pseudonym, is engraved. Unlike seals from other cultures that are imprinted onto wax or wet clay, an East Asian seal is imprinted on paper with a specialised vermillion paste.

Seals that were used to verify one’s identity were possibly the earliest form of Chinese art to arrive in Southeast Asia. Their impressions can be glimpsed in early documents, inscriptions, plaques, and temple artefacts. By the mid-19th century, there would likely have been local carvers who worked on seals within the Singaporean Chinese community, making them pioneers of the practice in Singapore.

The earliest-known seal album printed in Singapore is the Shihanzhai Seal Album, compiled in 1898 by Yeh Chih Yun (1859–1921, editor of Lat Pau), which contained around 180 imprints of seals completed after he had migrated south.1 It was not hard to see that Yeh’s influences were similar to those of late-Qing carvers, consisting of playful variations on the style of the Zhejiang School, which was known for its epigraphic emphasis. Yeh’s seal carvings reflected the styles popular in Nanyang at that time, such as mixed scripts, imitated leaf patterns, outlined characters, mixed red and white characters, and “hanging needle seal script”, which are deemed “heterodox” stylisations. These seal imprints are important early evidence that the history of seal carving in Singapore cannot simply be understood within the confines of the art form’s development in China.

Early generation of seal carvers

Following the Japanese invasion of China during World War II, a wave of Chinese seal carvers migrated to Singapore. Among them were Goh Teck Sian (1893–1962, arrived in 1938), See Hiang To (1906–1990, arrived in 1938), Chang Tan Nung (1903–1975, arrived around the 1940s), Wong Jai Ling (1895–1973, arrived in 1939), Tsai Wan Ching (1907–1970, arrived after 1939), Tan Keng Cheow (1907–1972, arrived in 1949), and Fan Chang Tien (1908–1985, arrived in 1956).2This generation of seal carvers was influenced to some extent by the modern Chinese art curriculum, which had begun to regard seal carving as a stream under the visual arts. They had established standards and concepts regarding the art history, stylistic schooling, and aesthetic theory of seal carving. While these artists’ seal carvings lacked some of Yeh Chih Yun’s capricious brilliance, they greatly contributed to the overall awareness and proficiency of seal carving in Singapore. Goh Teck Sian favoured the seal style of the Qin and Han dynasties, Tan Keng Cheow inherited the seal style of Wu Changshuo (1844–1927), popular in fine arts academies, from his teacher Huang Binhong (1865–1955), while Chang Tan Nung drew inspiration from seal styles popular at that time. All of them were prominent seal carvers of their generation.

In addition, there were several individuals such as Lin Qianshi (1918–1990), Tao Shoubo (1902–1997), and Feng Kanghou (1901–1983), who briefly stayed in Singapore or had close connections with local practitioners, and thus helped to nourish the local scene. During this time, the conditions for the exhibition and circulation of seal engravings had also taken shape in Singapore, with the printing of seal engraving catalogues, seal imprint panels, and the presence of organisations like the Nanyang Epigraphy, Calligraphy and Painting Society, which was established in 1948 with executive members such as seal carvers Wong Jai Ling, Tsai Wan Ching, and See Hiang To.3The market for seals in Singapore had thus outgrown the mainly practical requirements of the past.

Legacy of See Hiang To

The most influential figure in the development of seal carving in Singapore would undoubtedly be See Hiang To, who taught at Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA). See, also known as Hongze, was born into a family of scholars and artists in Zhangzhou, China. His father, Shi Gongnan (1880–1946), was also a calligrapher, painter, and seal carver, and their family had a considerable collection of books and materials. In 1975, See compiled and published the Lixianglou Seal Album, a collection of his father’s seal carvings.

See’s seal-carving style is diverse, combining characteristics from different sources, ranging from ancient scripts from bronzes and coins to imitations of contemporary masters such as Wu Changshuo, Zhao Zhiqian (1829–1884), and Qi Baishi (1864–1957). His seals exuded the “flavour of the knife” regardless of the style, exuding a strong sense of archaic beauty. Overall, his seals aligned with the prevailing styles in contemporary Chinese fine arts academies, which were particularly influenced by the Zhejiang School. From his seal albums, one can observe the solid foundation of his skills, which might have appeared somewhat too formalised but allowed him to educate the next generation of seal carvers during his tenure at NAFA, though without imposing his own style on them.

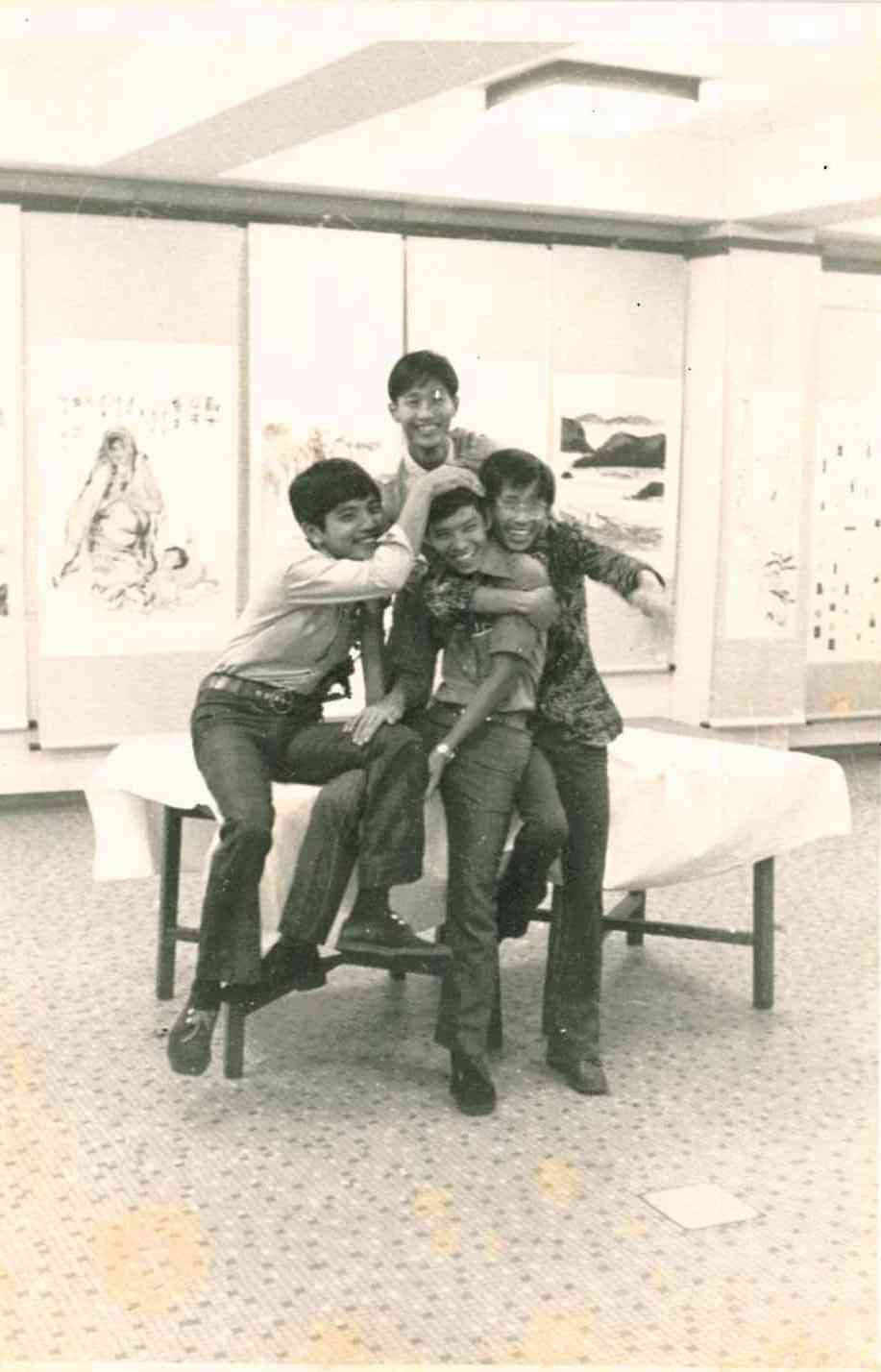

His students founded art societies that became the three pillars of Singapore’s seal carving community. Zhuang Shengtao and Oh Khang Lark founded the Molan Society in 1967, Tan Kian Por (1949–2019) and Tan Kee Sek founded the Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society in 1971, and Wee Beng Chong founded the Lanting Art Society in 1987.

Emergence of a Singapore style

As mentioned earlier, the subsequent generation of seal carvers had mostly encountered the practice through NAFA around the 1960s to 1970s, either as teachers, students, or through more informal contact. It is worth noting that at that time, NAFA did not formally establish a specialised seal carving programme. Instead, students pursued their interest in seal carving and sought guidance from their teachers on their own. As a result, more informal organisations such as art societies played a crucial role in the development and sharing of seal carving during this period.

Seal carving was a mature art form by the 1980s. Practitioners were not just producing seals with practical uses, but also creating more artistic works. In terms of form, they began exploring stylistic possibilities beyond the Ming and Qing tradition. This period marked the emergence of a unique seal engraving practice in Singapore, as the walling-off of China led to divergences in the two countries’ understanding of seal aesthetics.

This generation of seal carvers was much more vibrant compared to the earlier one. Some more senior seal carvers of this period were Lim Hui Eng (1921–1984), Tan Tee Chie (1928–2011), Lim Mu Hue (1936–2008), Liu Pao Kiang (1935–2023), and Lu Eng Wah. In addition to the five students of See Hiang To mentioned earlier, there were others like Tan Kin Chwee, Tan Chin Boon, and later-generation engravers such as Ho Bee Tiam, Teo Yew Yap, Oh Chai Hoo, and Lee Soon Heng.

In the 1970s, the publishing scene for seal albums had reached a period of maturity. Starting with Liao Baoqiang yinji (Seal Album of Liu Pao Kiang), published in 1963,4almost every seal carver published their own seal albums or participated in art society publications. This greatly strengthened the overall artistic community in Singapore, giving them more exposure to the art of seal engraving and better understanding of it.

New directions of Singapore’s seal carving

The first local publication that summarised the development of Singapore’s seal carving scene was Xinjiapo Zhuanke (Seal Carving in Singapore), published in 1976 to accompany an exhibition of the same name. It featured the works of 10 seal carvers and was foundational to the documentation of the practice in Singapore.5This catalogue demonstrated the emergence of the concept of a Singaporean seal carving practice in the 1970s. Siaw-Tao, together with Sibaozhai Gallery, later jointly organised and published four editions of Xinjiapo Yinren Zuopin Zhan/Ji (Singapore Seal Carvers’ Exhibition/Album) in 2002, 2004, 2006, and 2008.6These were important attempts to trace the history and current practice of Singaporean seal carving and have set the foundation for this article.

The publications were all organised by the seal carvers themselves, who attempted to frame the history of seal carving in Singapore through their own experiences. However, there remains a need for more critical and scholarly works on the topic.

Today, seal carving continues to be relevant to a new generation of practitioners in Singapore, who with their new cultural backgrounds and sources of aesthetic inspiration still find within the square inch of red pigment a potent opportunity for self-expression. Some new directions taken by Singaporean seal carvers today include the use of ceramics instead of stone, as well as a shift towards abstraction, local parlance, simplified Chinese, and the Singapore landscape.7These works forge a way ahead for a truly Singaporean practice of the ancient art form, and ensures the survival of the cultural practice long after the obsolescence of seals as verifiers of identity.

| 1 | Yeo Mang Thong, Goh Ngee Hui trans., Migration, Transmission, Localisation: Visual Art in Singapore (1886–1945) (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2019). |

| 2 | Refer to the seal albums published by the artists: Goh Teck Sian, Shouqin xuan zhuanke ji [Seals of Shouqin Studio] (Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, 200); See Hiang To, Xiangtuo yincun [Hiang To’s Seals] (Singapore: Shi Yiban, 1997); Chan Tan Nung, Zhang Dannong jiaoshou jinshi shuhua gezhan mulu [Catalogue of Professor Chan Tan Nung’s Exhibition of Seals, Calligraphy, and Painting] (Singapore: private publication,1949); Tsai Wan Ching, Shishu hua yincong bian [Collection of Poems, Calligraphy, Paintings, and Seal] (Singapore: Shizhong Publishers, 1964); Tan Keng Cheow, Chen Jingzhao jinshi shuhua ji [Collection of Tan Keng Cheow’s Seals, Calligraphy and Paintings] (Singapore: Singapore Chinese Calligraphy and Art Research Society, 1976); and Fan Chang Tien, Fan Chang Tien: The Timeless Ink Heritage (Singapore: artcommune gallery, 2019). |

| 3 | “Nanyang jinshi shuhua she juxing chengli dianli” [The Founding Ceremony for the Nanyang Epigraphy, Calligraphy and Painting Society], Nanyang Siang Pau, 3 February 1948. |

| 4 | Liu Pao Kiang, Liao Baoqiang yinji [Seal Album of Liu Pao Kiang] (Singapore: Shing Lee Bookstores, 1963). |

| 5 | Xinjiapo zhuanke [Seal Carving in Singapore] (Singapore: Exhibition Organising Committee, 1976). |

| 6 | Xinjiapo yinren zuopin ji [Singapore Seal Carvers’ Album] (Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy, and Painting Society & Sibaozhai Gallery, 2001); Xinjiapo yinren zuopinji, dier ji [Singapore Seal Carvers’ Album Vol. 2] (Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy, and Painting Society & Sibaozhai Gallery, 2004); Xinjiapo yinren zuopinji, disan ji [Singapore Seal Carvers’ Album Vol. 3] (Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy, and Painting Society & Sibaozhai Gallery, 2006); Xinjiapo yinren zuopinji, disi ji [Singapore Seal Carvers’ Album Vol. 4] (Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy, and Painting Society & Sibaozhai Gallery, 2008). |

| 7 | Carving Possibilities: An Exhibition by the Siaw-Tao Seal Carvers (Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society, 2023). |

Xinjiapo zhuanke [Seal Carving in Singapore]. Singapore: Exhibition Organising Committee, 1976. | |

Chan, Tan Nung. Zhang Dannong jiaoshou jinshi shuhua gezhan mulu [Catalogue of Professor Chan Tan Nung’s Exhibition of Seals, Calligraphy, and Painting]. Singapore: private publication, 1949. | |

Fan, Chang Tien. Fan Chang Tien: The Timeless Ink Heritage. Singapore: artcommune gallery, 2019. | |

Goh, Teck Sian. Shouqin xuan zhuanke ji [Seals of Shouqin Studio]. Singapore: Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts, 2001. | |

Liu, Pao Kiang. Liao Baoqiang yinji [Seal Album of Liu Pao Kiang]. Singapore: Shing Lee Bookstores, 1963. | |

See, Hiang To. Xiangtuo yincun [Hiang To’s Seals]. Singapore: Shi Yiban, 1997. | |

Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society, ed. Carving Possibilities: An Exhibition by the Siaw-Tao Seal Carvers. Singapore: Siaw-Tao Chinese Seal-Carving, Calligraphy and Painting Society, 2023. | |

Tan, Keng Cheow. Chen Jingzhao jinshi shuhua ji [Collection of Tan Keng Cheow’s Seals, Calligraphy and Paintings]. Singapore: Singapore Chinese Calligraphy and Art Research Society, 1976. | |

Tsai, Wan Ching. Shishu hua yincong bian [Collection of Poems, Calligraphy, Paintings, and Seal]. Singapore: Shizhong Publishers, 1964. |