An overview of Singapore’s Chinese Music scene

Early Chinese immigrants to Singapore consisted of two main groups: the Peranakans and the sinkehs. The Peranakans were descended from Chinese settlers who had arrived in Singapore before the 19th century and married local Malay women. Over the generations, they blended Chinese, Malay, and British colonial traditions, forging a unique cultural identity. The Peranakans did not have a music genre of their own. Rather, their music was inspired by many sources, including Western pop, jazz, Hawaiian melodies, and Latin music such as cha-cha-chá and mambo. Peranakan musicians created an eclectic blend of Nanyang (Southeast Asian) and Western musical styles. The medley of cultural influence is seen in the use of the Malay serunai (a type of wind instrument) to adopt popular Hokkien tunes during weddings, funerals and other events. The Peranakan community especially enjoys music influenced by Western and Malay popular music. This can be seen in the prevalence of performances featuring small musical ensembles playing dondang sayang and kroncong — Malay love ballads and folk songs respectively. From violins to guitars and ukuleles, Peranakan musicians harmoniously integrate these Western instruments with the rhythms of the Malay rebana (frame drum) and knobbed gong.

In addition to standalone musical performances, the dondang sayang accompanies performances of pantun (a Malay poetic form), bangsawan (an operatic form popular in the Malay peninsula), and wayang peranakan (Peranakan musical theatre). The Peranakans founded numerous amateur musical societies during the British colonial era. These groups provided a good source of entertainment at family gatherings, and also performed publicly for commercial gigs and festive celebrations.1

Music of the “Sinkehs”

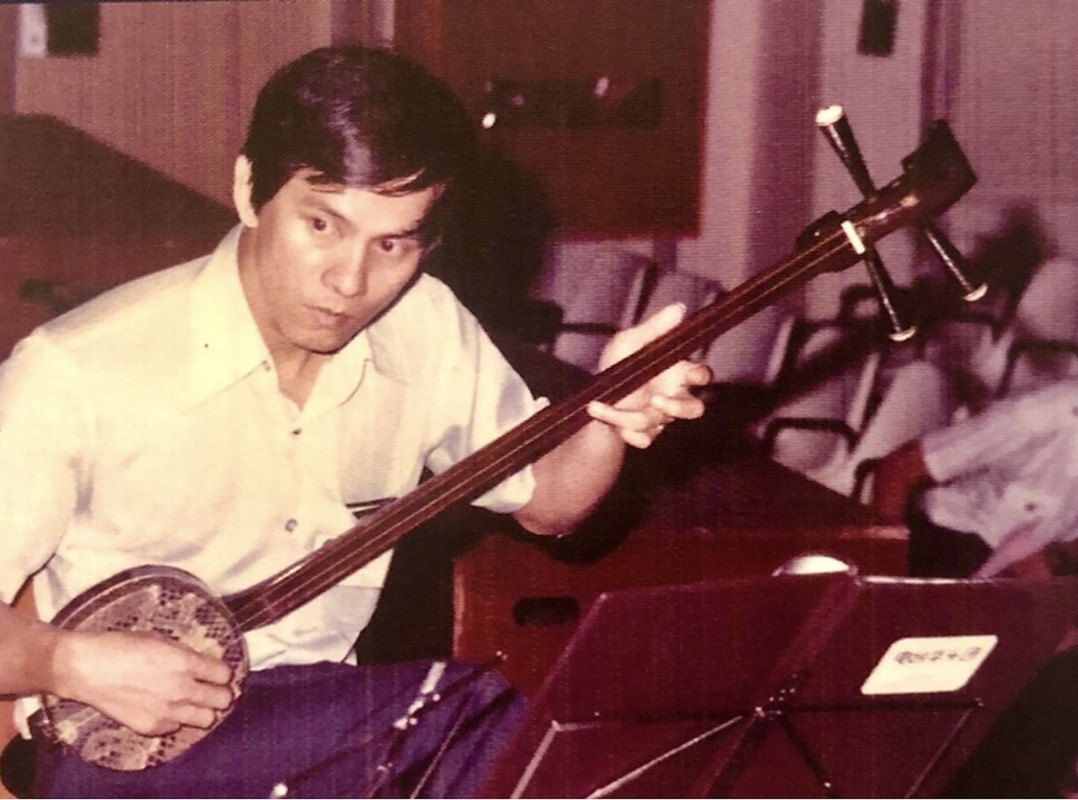

Meanwhile, the sinkehs (“newcomer” in Hokkien) were Chinese immigrants who relocated to Singapore from various regions of China between the 19th and early 20th centuries. Originating from a range of dialect groups, they included the Hokkiens (from Fujian), Cantonese (from Guangdong), Hainanese (from Hainan), Teochews (from Chaozhou), and Hakkas. They brought their native musical instruments and traditions to Singapore.

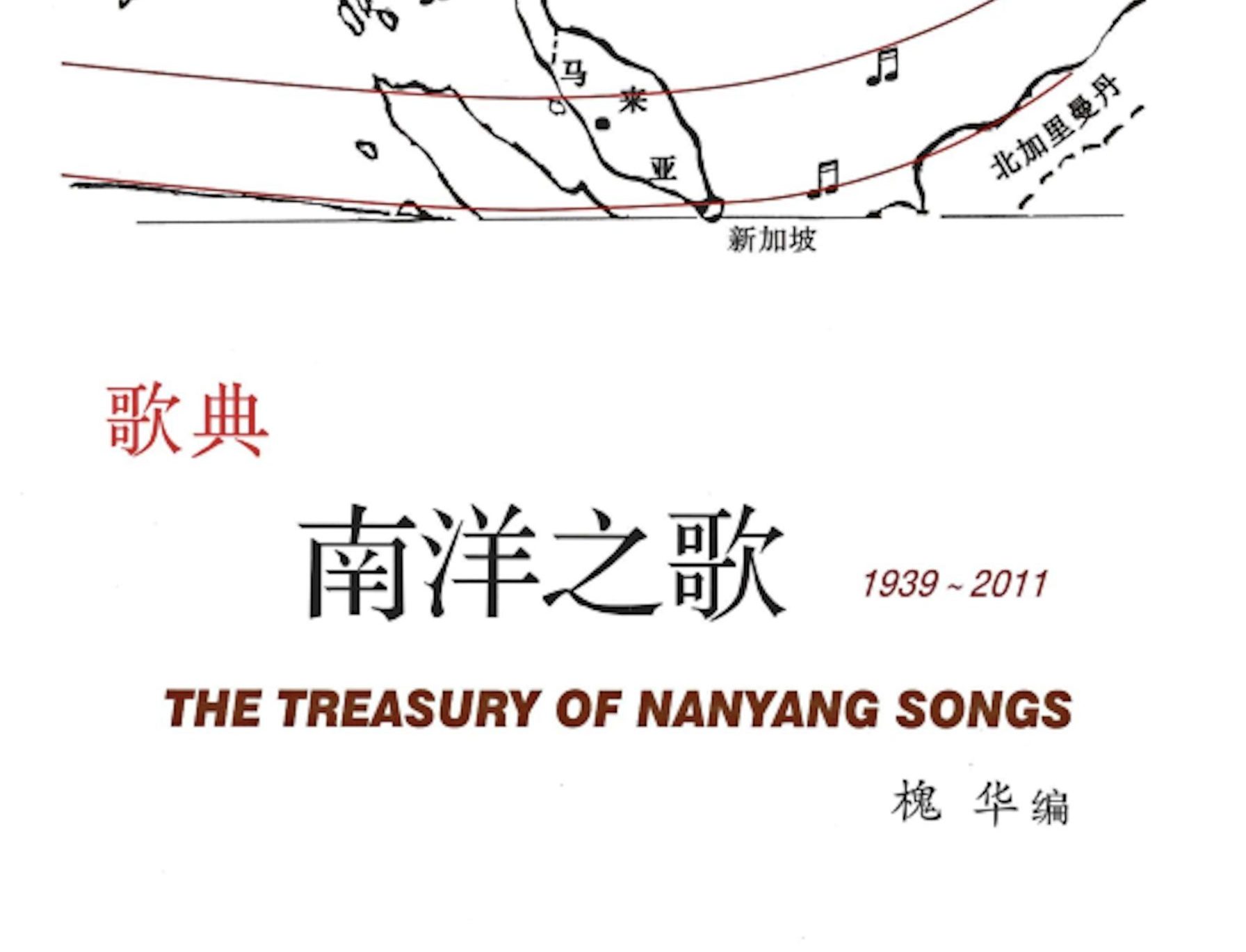

The musical and artistic pursuits of the Chinese immigrants flourished particularly during Chinese festivities. These included deities’ birthdays, auspicious celebrations, and even funerals. Over time, the sinkehs established various clan associations or huiguan, which not only acted as hubs for social and emotional connection but also played pivotal roles in fostering the development of Chinese music in Singapore. Chinatown was initially the heart of this musical development. From there, it spread to nearby areas such as Dapo (South Bridge Road) and Xiaopo (North Bridge Road). The establishment of three major amusement parks in Singapore — New World, Great World, and Gay World (formerly Happy World) — marked a milestone in the history of Singapore’s Chinese music scene.2 These attractions drew numerous acclaimed musicians and actors from China to perform in the Nanyang region. Their high-calibre performances encouraged many local musical groups to professionalise.

Importantly, local musical groups were instrumental during pivotal moments in Singapore’s history. They supported fundraising for China’s revolutionary causes, contributed to the anti-Japanese resistance, and provided aid to refugees. The years of the Japanese Occupation (1942–1945) saw Singapore’s musical organisations struggle for survival. Subsequently, the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 made it challenging for China’s musical groups to perform overseas. Under such circumstances, the traditional musical groups in Singapore began to localise and evolve into amateur groups.3

Two Categories of Singapore’s Chinese Music

Singapore’s Chinese music falls broadly into two categories: dialect-based music genres and pan-Chinese music genres. A detailed subdivision of these genres is shown in the following table:

Singapore’s Chinese music

- Traditional music

- Religious music

- Nursery rhymes

- Dialect pop music (primarily from the Hokkien and Cantonese communities)

Pan-Chinese music genres

- Shiyue (Poetry-music)

- Xinyao (Mandarin ballads by Singapore youth)

- Chinese orchestra music

- Getai (live stage performance)

- Mandarin pop music

- English pop music (covered by Chinese artistes)

- Western-style Chinese music

Traditional music of Singapore’s Chinese dialect communities

- Folk songs: sung poetry and children’s songs

- Local opera: liyuan opera, gaojia opera, and Hokkien opera (also known as min, xiang, and gezai operas)

- Narrative arts: Hokkien nanyin (literally ‘southern sounds’), traditional storytelling, and jin songs

- Instrumental music: Hokkien nanyin

- Folk songs: mountain songs, fishing songs, and children’s songs

- Local opera: Qiongju (Hainanese opera)

- Instrumental music: Hainan bayin (literally ‘eight tunes’)

- Folk songs: mountain songs, xiaoqu (folk tunes), shiye (literally ‘master advisor’) songs, and children’s songs

- Local opera: Guangdong Hakka Han opera

- Instrumental music: Guangdong Han music or Hakka Han music (also known by its earlier name, waijiang music), Hakka string instrument music, zhongjunban (ceremonial music, also known as bayin), Han big gongs and drums music, and temple music

- Folk songs: xianshui (literally ‘saltwater’) songs, tanqin, (literally ‘sighing zither’), muyu (literally ‘wooden fish’; temple block) songs, mountain songs, xiaoqu (folk tunes), dance songs, and children’s songs

- Local opera: yueju (Cantonese opera)

- Narrative arts: muyu songs, shuoshu (storytelling), yuequ (Cantonese opera), xiangsheng (literally ‘crosstalk’; comic dialogue), and yue-ou (narrative verses)

- Instrumental music: namo (chants), Guangdong string instrument music, Foshan ten-gongs and drums set, and Guangfu bayin (Cantonese ‘eight tunes’)

- Folk songs: Teochew gezai songs, rites and ritual songs, and children’s songs

- Local opera: Chaoju (Teochew opera) and baizi opera

- Narrative arts: Chaozhou or Teochew kuaiban (literally ‘fast beats’) and Teochew xiangsheng (literally ‘crosstalk’; comic dialogue)

- Instrumental music: Teochew big gongs and drums, Teochew string instrument music, Teochew woodwind traditional music, Chaoyang woodwind and percussion, Teochew waijiang gongs and drums, Teochew small gongs and drums, Teochew xiyue (plucked string ensemble), and Teochew shantang (charity halls) music

Grassroots and government

Independent Singapore was built on the bedrock of multiculturalism. This ethos, combined with the integration of the Chinese community with other ethnic groups, significantly enriched the Singaporean Chinese music scene. With the establishment of the National Theatre in 1963 and the Kreta Ayer People’s Theatre in 1969, musicians of various Chinese dialect groups and musical genres found prominent stages to showcase their talents.

As participation in music and the arts became a social trend, local audiences ardently supported performances by both domestic musical groups and visiting overseas artistes. Concurrently, the Singaporean government ramped up its endorsement of the arts as part of its nation-building initiative, and positioned Chinese music as a symbol of ethnic culture.4

However, the 1979 nationwide Speak Mandarin Campaign shifted the landscape and sidelined dialects from the national education policy. This led to a decline in the popularity of dialect- or locality-based musical groups between 1980 and 2010. During this lull period, support for traditional, dialect-based music and culture largely hinged on grassroots initiatives. There has been a marked policy shift in recent years: the Singaporean government has been actively reviving traditional Chinese culture. It has championed academic seminars and supported the establishment of the Singapore Chinese Cultural Centre, heralding a new era in the evolution of traditional Chinese culture in Singapore. The trajectory of Chinese music in Singapore epitomises the synthesis of grassroots passion and governmental support, ensuring the enduring legacy of Chinese musical traditions for future generations.

Shielded from the impact of China’s Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), Singapore’s Chinese music culture largely preserved its originality. Notably, the confluence of diverse ethnicities and cultures over time has deeply enriched and infused a distinct local flavour into the Chinese music scene. The accumulation of a century of cultural interaction and experimentation has crafted today’s distinctive Singapore Chinese music soundscape. This allows Singapore’s Chinese music to showcase its unique local character while also reflecting a rich mosaic of influences. The melodies of immigrant Chinese, Peranakan, and contemporary Chinese musicians interweave to form a vibrant tapestry of Singaporean Chinese music.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡华人音乐概论. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | Lee Tong Soon, “Peranakan music and multiculturalism in Singapore”, 207–213. |

| 2 | Wong Chee Meng, Youying zhen tiansheng: niucheshui bainian wenhua licheng, 29–35, 218. |

| 3 | Yi Yan, Liyuan shiji: Xinjiapo huazu difang xiqu zhi lu, 69–73. |

| 4 | Yi Yan, Liyuan shiji: Xinjiapo huazu difang xiqu zhi lu, 163. |

Dairianathan, Eugene and Phan, Ming Yen. “A Narrative History of Music in Singapore 1819 to the Present”. Technical report submitted to the National Arts Council, Singapore, based on the award of the research grant in 2002. Internal document. | |

Koh, Chin Yee. Buyi nandu: Zhongguo minjian wenyi zai Xinjiapo de chuanbo yu bianqian [Propagation and Transformation of Chinese Folklore Literature in Singapore]. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 2018. | |

Lee, Tong Soon. “Peranakan music and multiculturalism in Singapore”. In Routledge Handbook of Asian Music: Cultural Intersections, edited by Lee Tong Soon, 204–220. New York: Routledge, 2021. | |

Wong, Chee Meng. Youying zhen tiansheng: niucheshui bainian wenhua licheng [A Century of Singapore’s Chinatown in Cultural and Historical Memory]. Singapore: Global Publishing, 2019. | |

Yi, Yan. Liyuan shiji: Xinjiapo huazu difang xiqu zhi lu [Hundred Years Development of Singapore Chinese Opera]. Singapore: The Singapore Chinese Opera Institute, 2015. |