Modern and contemporary art in Singapore

There is often confusion between the Chinese terms xiandai “现代”, meaning “current times”; and dangdai “当代”, meaning “of that time”. In art, however, xiandai means “modern”, while dangdai means “contemporary”: the latter comes after the former in art history. So the time sequence appears reversed in art discourse, causing much confusion to the general public. This is because “modern” in art discourse refers to historical modernism in Western art history, a period that had been surpassed by “contemporary”, which comes after. What comes after modernism, sometimes expressed as “postmodernism”, becomes “contemporary”. In art historical discussion, these are often followed by arguments for “proto-”, “high-”, “hyper-”, “post-” modern/contemporary art, and so on. All these positions are predicated on modern and contemporary as a set of time sequences and based on a contrasting binary. However, exactly how these terms are used depends on perspectives. They are also used to demark identities, to highlight preferences and differences. Notwithstanding the general time sequence, it is natural to expect overlaps and disagreements, or even refusal to associate these terms with specific artworks, practices, and artists. In Singapore, where the National Gallery Singapore and Singapore Art Museum identify themselves with modern and contemporary art respectively, this division between modern and contemporary becomes even more reified.

Determining when “modern” and “contemporary” art occurred depends on how these terms are defined. The Indian art historian Geeta Karpur famously noted in her seminal essay “When was Modernism?” that it is important “to see our trajectories crisscrossing the Western mainstream and, in the very misalignment from it, making up the ground that restructures the international”.1The question of “when” is largely determined by “what”. In Singapore, discussions about the “modern” often avoid a specific temporal point or suggest several different starting points for consideration. In an article whose title referenced Karpur, “When was Modernism: A Historiography of Singapore Art”, Kevin Chua noted several of these points to discuss the implications of each. These include the late 19th century, 1920s to 1960s, and 1970s to 2000s.2

It is useful to refer to the two readers edited by Jeffery Say and Seng Yu Jin titled Intersections, Innovations, Institutions: A Reader in Singapore Modern Art (2023), and Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art (2016). The scopes of the two books focus on modern and contemporary art in Singapore. In the modern art reader, Say and Seng noted that the modern art reader was more challenging to put together due to the wider timespan and also “to the contested notion of the ‘modern’ in Singapore art”. The editors went on to state that “rather than a singular modernism, we argue that there were multiple trajectories that intersected with migrations of populations from China and India to Singapore…”3 Unlike in the case of contemporary art, no specific timeframe was mentioned for modern art in Singapore. In “Contemporary Art”, the same editors were more willing to put some dates to its inception: “In the context of Singapore, contemporary art refers to the emergence of conceptualism in the 1970s and, notably, the proliferation of experimental and process-based art practices in the late 1980s as distinct from the visual arts — painting and, to some extent, sculpture, printmaking, and photography — that had characterised much of post-war Singapore art.”4

Chinese modern art and Nanyang feng

In the case of modern art in China, it is often discussed in relation to a broader modern cultural and intellectual historical landmark, that of the May Fourth Movement (1919). The May Fourth modernity in art took several diverse, if not contradicting directions. The Chinese art historian and critic Li Xianting in a 2024 talk at the National Gallery Singapore noted that there were two successive May Fourth waves in art. First was the rejection of the ink painting tradition, which came along with a counter-wave of rejuvenating the literati aesthetics in the new global context. Second was the introduction of turn-of-the-century Western modernist art such as postimpressionism, abstraction, cubism, and surrealism, only to be met with another counter-wave that privileged realism. Li explained that the latter subsequently became the mainstream 20th-century art in China all the way until the 1980s.5

Not unaffiliated with the art development in China, within the ethnic Chinese community in Singapore, realism was also the main art style of modern art until the late 1950s. Art historian Yeo Mang Thong calls such realism “Nanyang Feng” (南洋风), to be differentiated from another term, “Nanyang Style”.6Until the formation of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, there were many exchanges in the modern art of realist variants with China, which extended to discourses in modern art and aesthetics from the 1920s onwards. Contemporary art in Singapore is often seen as a departure from the formalist Nanyang Style.7

Multiple modernities and “modernisms” in Southeast Asia

In marking developmental time sequences, the technological world prefers “versions”, such as 1.2, 3.5, and so on. However, art is not predicated on neat linear development. Although Western modernism has significantly influenced artistic expression worldwide, the influence of non-Western and Indigenous cultures and aesthetics on Western art is less recognised. Indonesian art historian Jim Supangkat has emphasised the importance of acknowledging multiple modernities and “modernisms” in Southeast Asia. He argues that the path to modernity has always been a unique combination of local traditions and global sources of modernity, not limited to Western developments. In Singapore, we can further relate art and aesthetic developments to even narrower communal, cultural, and linguistic contexts. As artists and scholars examine the historical period of the “modern”, the term “contemporary” has taken on the meaning of a departure or break from established art practices of the earlier modern era. However, as Say and Seng remarked, which modernism or modernist art practice is the concern?

To facilitate discussions on modern art in Singapore, it is suggested that the mid-20th century — specifically the 1950s and 1960s — be designated as a key timeframe for modern art in Singapore. This period serves as a crucial reference point, with the boundaries potentially extending earlier or later depending on the specific focus of the conversation.

New forms, new materials, new attitudes

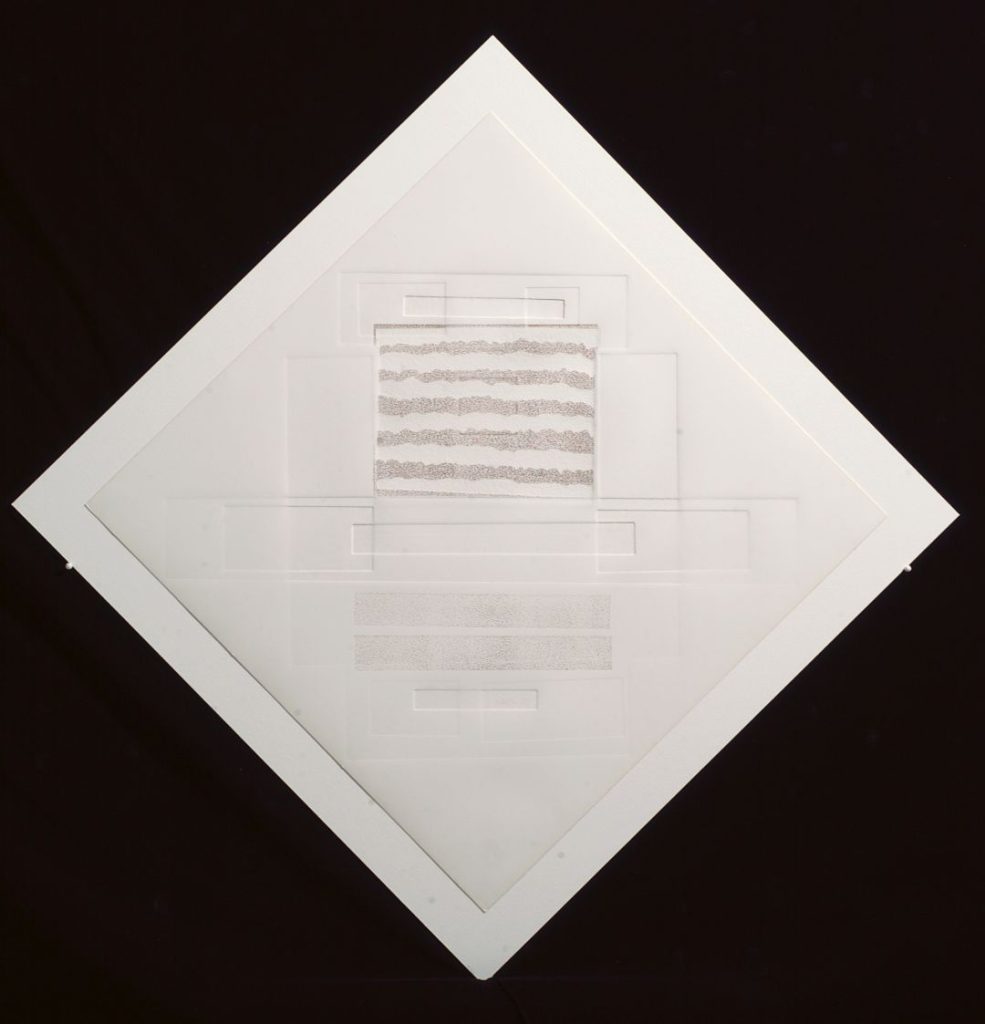

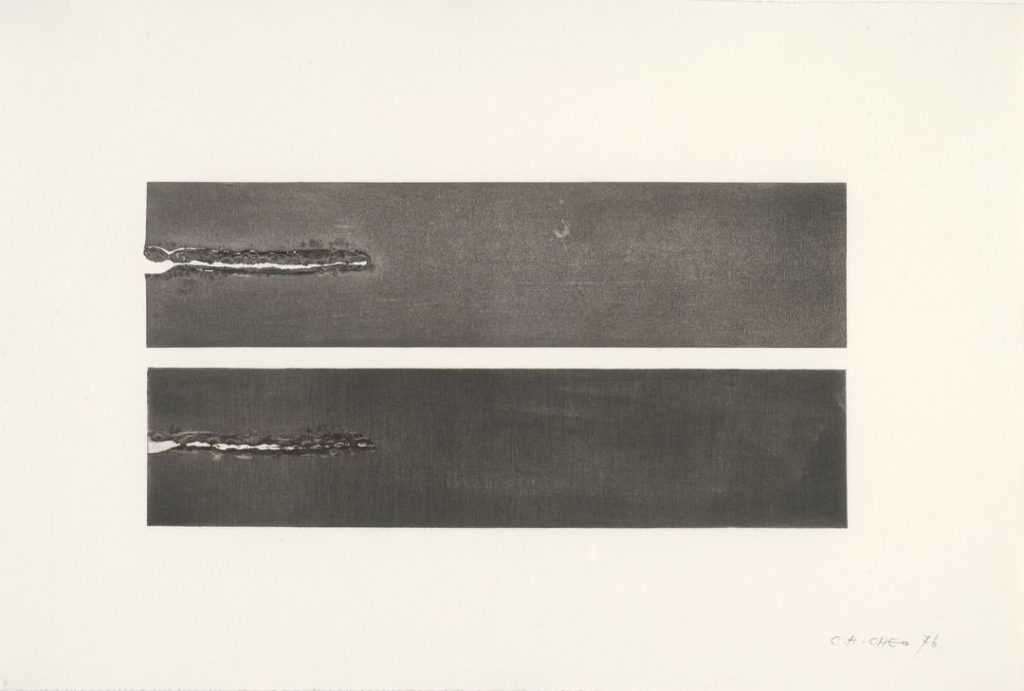

The difference between modern and contemporary art is also often spoken of as pointing to different art forms and mediums. While painting and sculpture are “modern”, new media, conceptual photography, installations, and performance art are “contemporary”. However, one of the earliest texts articulating contemporary art in Singapore noted the new art as a departure from a medium-centered approach to art. Artist Cheo Chai-Hiang noted, “In today’s art, the medium itself is no longer of such importance.” 8 Written in Chinese by Cheo and published in Singapore Monthly in 1972, Cheo noted that “the main characteristic of present-day art is no longer the manipulation of interrelationships in visual space, but one which focuses on human activities… What we should be concerned with are not the individual forms of expression, but with the new concepts that influence the directions of art — new forms, new materials, and new attitudes.”9

Although Cheo did not explicitly use the term “contemporary”, his description of “new art” can be seen as a significant starting point for contemporary art in Singapore. Interestingly, this early iteration was written in Chinese, despite the Chinese terms xiandai and dangdai being reversed in time sequence in their usage.

Say and Seng noted that contemporary art in Singapore refers to the emergence of conceptualism in the 1970s. Cheo’s 1972 article argued that contemporary art is socially oriented towards broader human concerns and influenced by “new concepts” that influenced its direction, unlike earlier art forms that were individualistic expressions. This was also the main argument for conceptualism in Western art, where “concept” represented social concern in favour of individual expression.

‘New art’: Contemporary art in Singapore

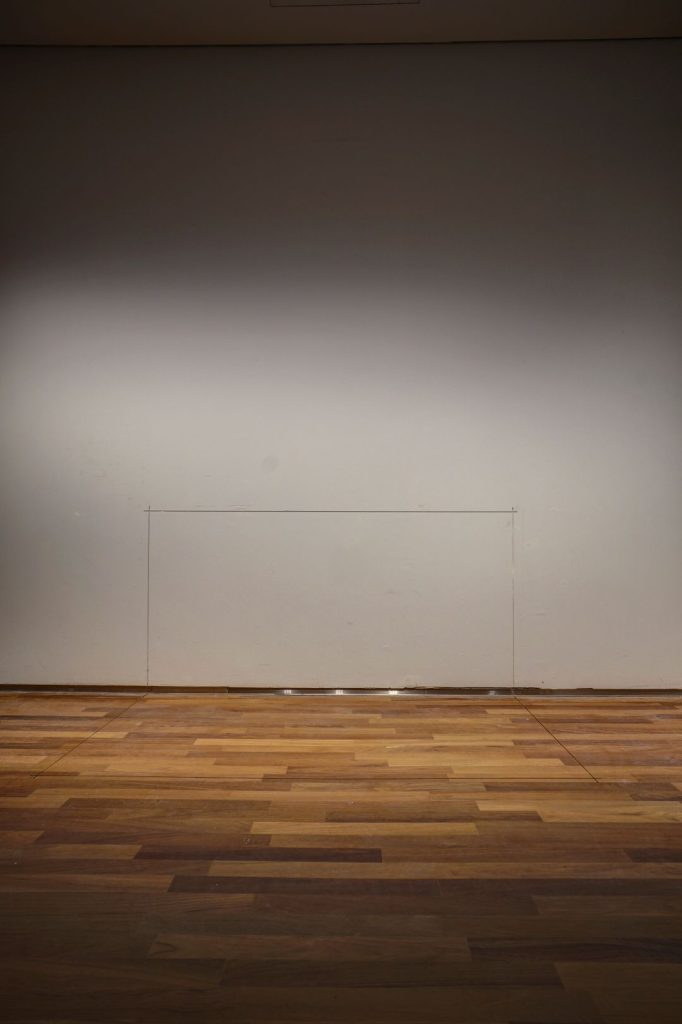

Cheo demonstrated his new art with a submission titled 5’ x 5’ (Singapore River) to the Modern Art Society’s annual exhibition in the same year (1972). Cheo’s conceptual art comprised a set of written instructions to mark out a five-by-five-foot square outline straddling the wall and floor. This proposal was not accepted by the exhibition’s organisers. The society’s president, Ho Ho Ying (1935–2022), who later received the Cultural Medallion in 2012, wrote a long response to Cheo’s proposal. One of Ho’s concerns was how the audience would respond to his work: “When an artist is able to work freely, the viewer is also able to exercise his freedom to select what he wishes to look at… Most artists are reasonable members of society and we are keen to contribute to the society that nurtures us… the communication between the artist and the viewer should go both ways.”10

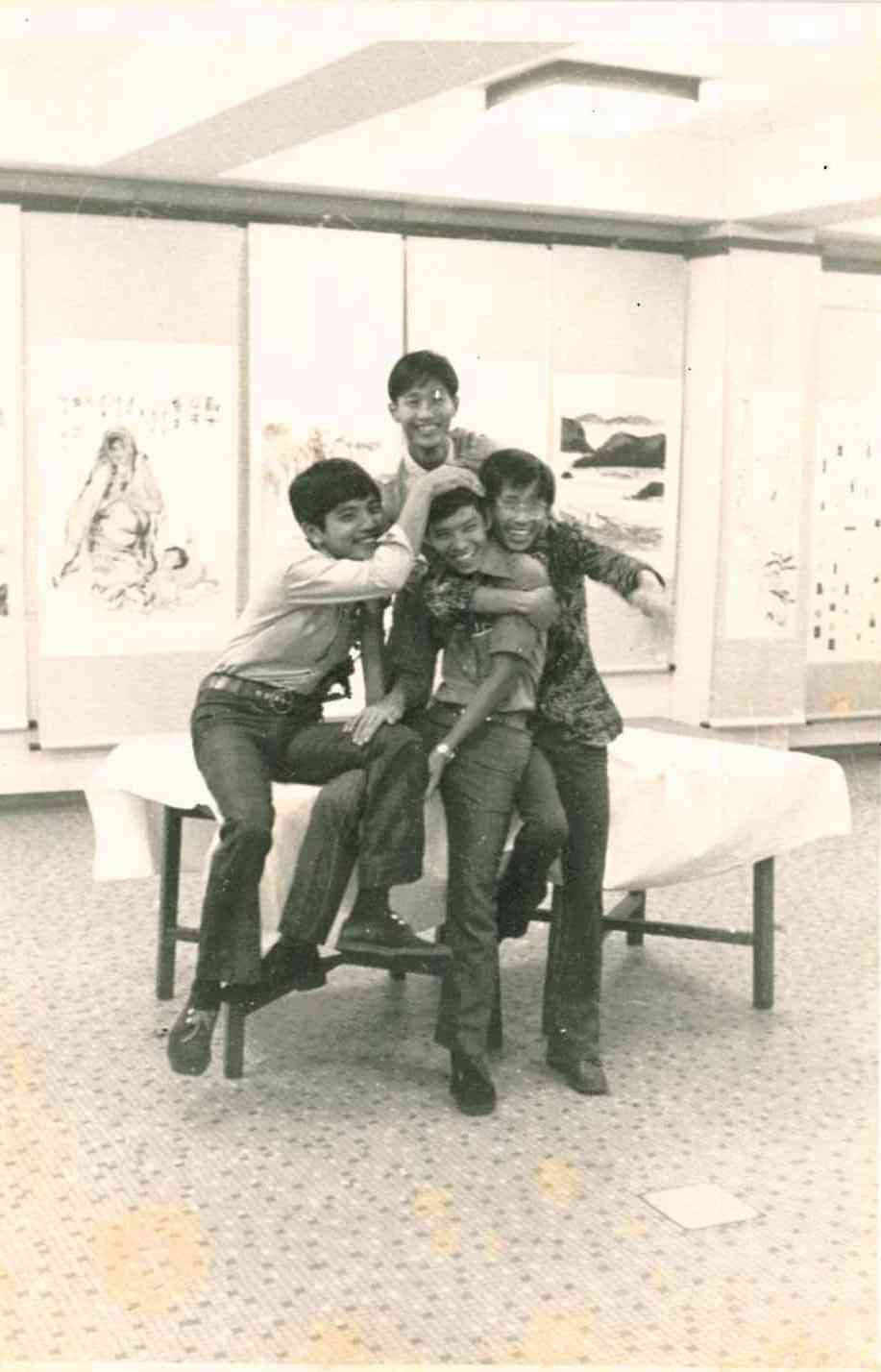

Beyond 5’ by 5’, several significant works, such as Tan Teng Kee’s The Picnic (1979), can be considered examples of early contemporary art in Singapore. During the “picnic” event, Tan burnt a work fittingly titled Fire Sculpture.11 The Artists Village, founded by Tang Da Wu in 1988, is known for its collective efforts to further contemporary practices. The social inquiry method in contemporary art had a distinctive approach that involved experimentation and a process-oriented outlook. It also engaged pedagogy, which is characteristic of the installation and performance art of Tang Da Wu, and arguably a notable characteristic of contemporary art in Singapore in general. Tang is also known for his drawings and paintings, including those in the ink medium, in addition to his installation and performance works.

When exploring contemporary art practices and discourse in Singapore, the notion of “concept”, as highlighted by Cheo, Say, and Seng, may be identified as a crucial factor in differentiating modern and contemporary art. However, all works of art have a concept, even if they are “untitled”. In contemporary art, the concept is often in the formation phase (the concept-in-formation discussed above) as opposed to being a clarifying category). This raises the question of how to distinguish between contemporary and modern art in Singapore and how to establish a “break” from past practices to justify a new phase of contemporary art. One may characterise this contemporary conceptualism as articulations always in formation, that is, questioning, critical, and engaging the audience in mutual formation of observations and criticality.

At the turn of the millennium, major global art institutions sought to make their exhibition programmes and collections more geographically inclusive. At the same time, they were also claiming authority over the emerging category of “contemporary art”. This trend was particularly evident in the global contemporary art scene. It was no surprise that the highly regarded Singapore contemporary artists were recognised locally as well as through global programmes such as Documenta (Kassel, Germany) and Asia Pacific Triennale (Brisbane, Australia), as noted by curator Huangfu Binghui in a 1999 article. Among those prominent artists were S. Chandrasekaran, Suzann Victor, Lee Wen (1957–2019), Amanda Heng, Simryn Gill, Matthew Ngui, and Tang Da Wu.12

| 1 | Geeta Karpur, “When was Modernism?”, South Atlantic Quarterly 92, no. 3 (Summer 1993). This quote is from her presentation, “When was Modernism in Indian Art/Third World Art” at the “Theories of Visual Arts Conference”, the Institute of Higher Studies in Art, Cambridge University, 1992. |

| 2 | Kevin Chua, “When Was Modernism? A Historiography of Singapore Art”, in Charting Thoughts: Essays on Art in Southeast Asia (Singapore: National Gallery Singapore, 2017), edited by Low Sze Wee and Patrick D. Flores. |

| 3 | Jeffery Say and Seng Yu Jin, eds., Intersections, Innovations, Institutions: A Reader in Singapore Modern Art (Singapore: World Scientific Publishing, 2023), xviii–xix. |

| 4 | Jeffery Say and Seng Yu Jin, eds., Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art (Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, 2016), 6–7. |

| 5 | Li Xianting, “New Literati Spirit in Contemporary Chinese Ink”, New Moons Ink Art Lecture 2024 held at the National Gallery Singapore, 19 October 2024. |

| 6 | Yeo Mang Thong, “Jiema Nanyang feng” [Decoding Nanyang Feng], Fifth Liu Kang Annual Lecture held at the National Gallery Singapore, 5 April 2022. |

| 7 | See T. K. Sabapathy, “The Nanyang artists: Some general remarks”, in Pameran Retrospektif Pelukis-Pelukis Nanyang, 43. |

| 8 | Cheo Chai-Hiang, “Xin de yishu, xinde guannian” [New art, new concept], Singapore Monthly (1972). This English translation is by Lai Chee Kien. |

| 9 | Ibid. |

| 10 | Ho Ho Ying, “Art, Besides Being New, Has to Possess an Intrinsic Quality in Order to Strike a Sympathetic Chord in the Hearts of the Viewers”, in Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art, edited by Jeffrey Say and Seng Yu Jin, 45. |

| 11 | Jeffery Say’s “Groundbreaking: the Beginnings of Contemporary Art in Singapore” has a comprehensive list of these early contemporary artworks. See Say, “Groundbreaking: The Beginnings of Contemporary Art in Singapore”, BiblioAsia (July–September 2019). |

| 12 | Binghui Huangfu, “Home Grown: Installation/Conceptual Artists in Singapore”, in Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art, 344. |

Muzium Seni Negara Malaysia, ed. Pameran Retrospektif Pelukis-Pelukis Nanyang [Nanyang Artists: A Retrospective Exhibition]. Kuala Lumpur: Muzium Seni Negera, 1979. | |

Say, Jeffery. “Groundbreaking: The Beginnings of Contemporary Art in Singapore”. BiblioAsia, July–September 2019. | |

Say, Jeffery and Seng, Yu Jin, eds. Histories, Practices, Interventions: A Reader in Singapore Contemporary Art. Singapore: Lasalle College of the Arts, Institute of Contemporary Arts Singapore, 2016. |