Pioneer musician: William Gwee Thian Hock

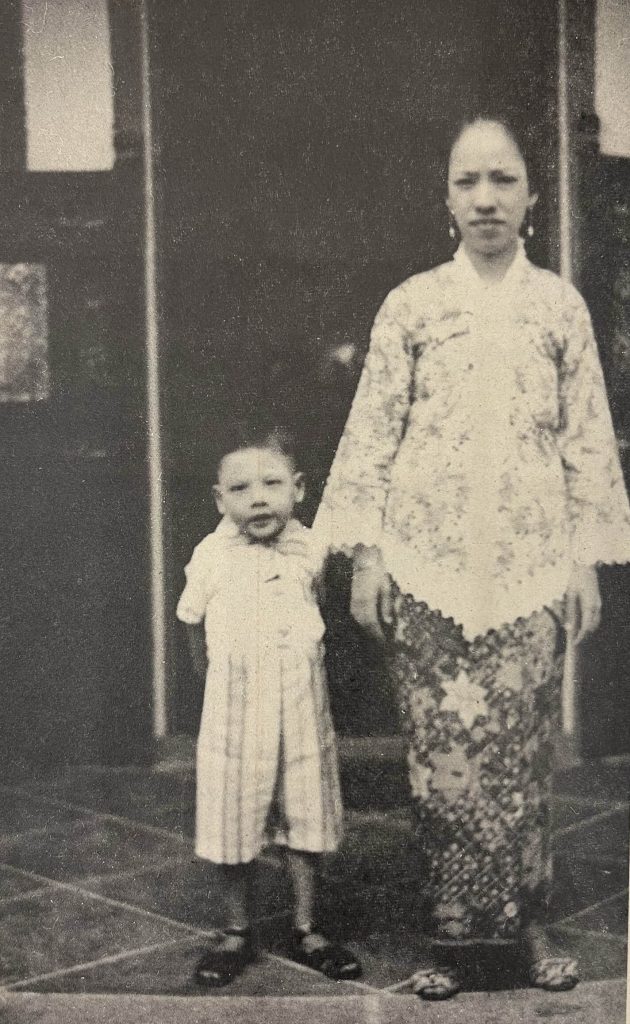

William Gwee Thian Hock (1934–2024) grew up in a traditional Chinese Peranakan family.1 His family can be traced back five generations to an ancestor in Malacca.2He is the fifth of eight children and the second of three sons. He is the son of Gwee Peng Kwee (1901–1986), a well-known dondang sayang (traditional Malay verse song) singer and former president of the Gunong Sayang Association. His brother GT Lye is a prominent Peranakan stage actor.3 Gwee attended Choon Guan English School4as a boy before the Japanese Occupation. After World War II, he continued with his studies and was eventually trained as a pharmacist. He worked at Alexandra Hospital until his retirement in the 1980s.5

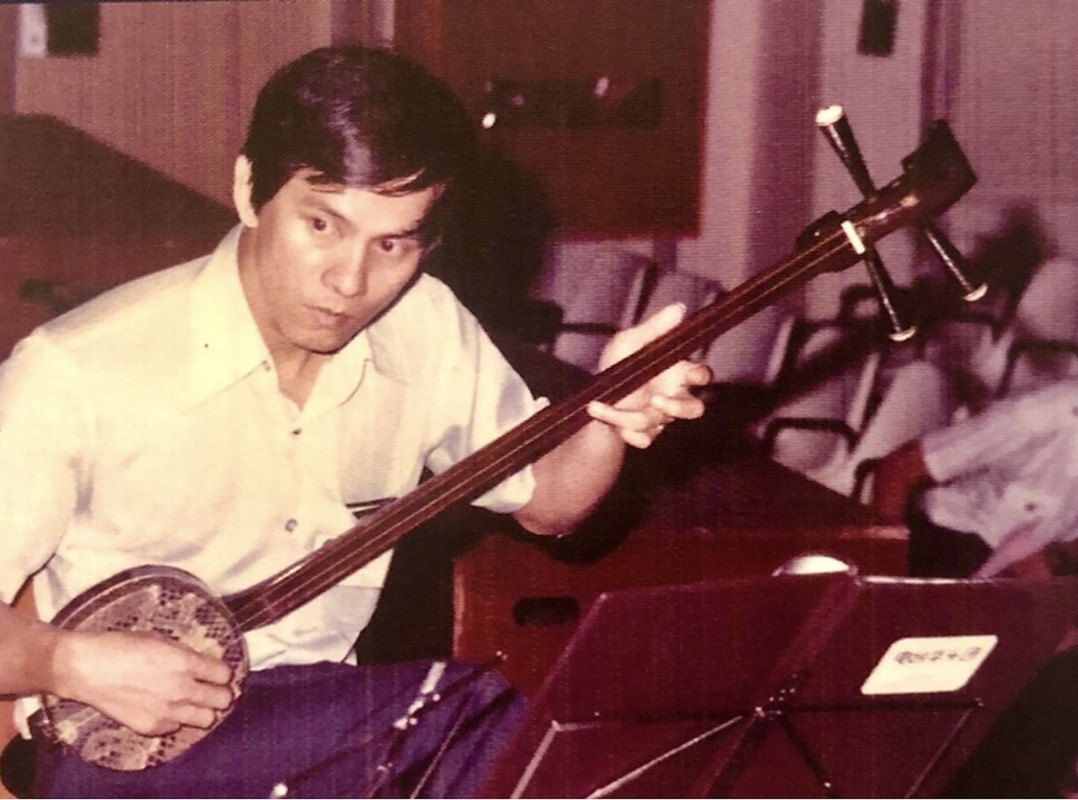

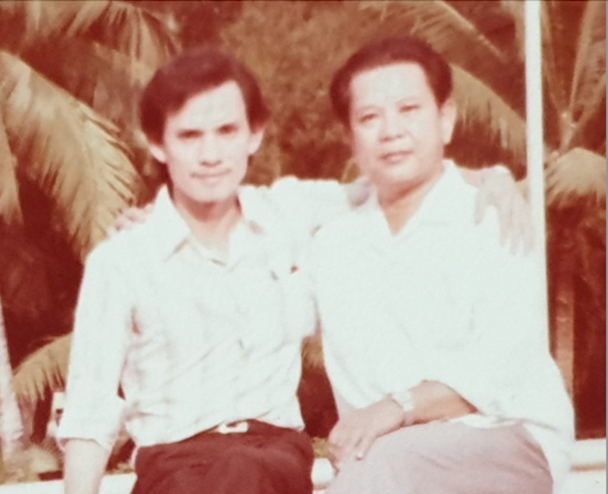

Gwee grew up in a household that exposed him to all aspects of Peranakan culture, which would later inform his writing. His father Gwee Peng Kwee, who taught him the piano, was an accomplished musician and an expert improviser of pantun (a form of Malay verse). The elder Gwee would organise musical groups and perform during festive days for family and friends, and have his son help him with his musical productions for the Gunong Sayang Association in the 1950s and 1960s. It therefore comes as no surprise that the younger Gwee should have developed an interest in both the musical and literary aspects of Peranakan culture.

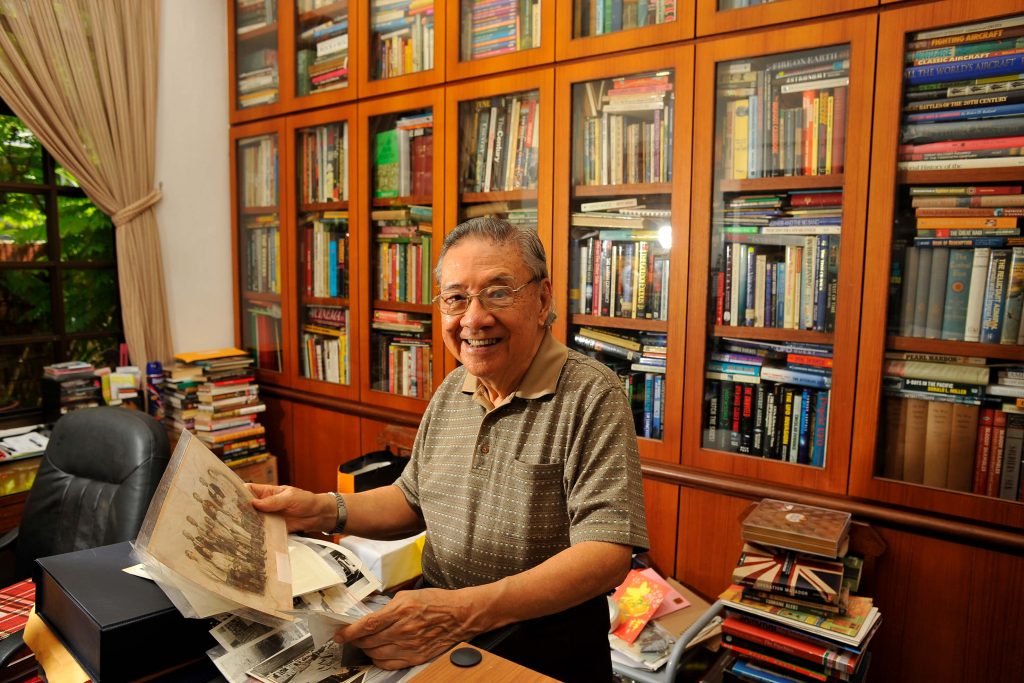

Retirement from his pharmacist job gave Gwee time to write. A Nonya Mosaic: My Mother’s Childhood was published in 1985. This was a memoir of his mother, Seow Leong Neo’s life, where he recounted in detail the clothes, cuisine, festivities and daily activities of Peranakan culture and life from his childhood. This was followed by Mas Sepuloh: Baba Conversational Gems in 1993 and A Baba-Malay Dictionary in 2006. These served to document much of the unique Baba Malay language. A memoir, A Baba Boyhood was published in 2013.

Perhaps due to a variety of factors, one being his association with his father Gwee Peng Kwee’s work with the Gunong Sayang performances, the other being his books detailing Peranakan culture, Gwee came to be known in the Peranakan community for his extensive knowledge of Peranakan customs, food and language. Another factor could have been his active contributions to the Peranakan Association’s newsletter over the years.6From the 1980s, Gwee has often been consulted on matters related to Peranakan customs and language by various public organisations and researchers. The most notable of which was Felix Chia’s play Pileh Menantu, performed at the 1984 Singapore Festival of Arts.

Music and lyrics for Baba plays

Gwee went on to write several Baba plays for the Gunong Sayang Association in the 1990s.7These included Manis Manis Pait (Bittersweet), Kalu Jodoh Tak Mana Lari (Love’s Destiny), Bulan Pernama (An Auspicious Full Moon), and Janji Perot.8 Gwee’s creative contributions included writing the lyrics and music of the songs in the shows. These plays were directed by Richard Tan, who ever since his first collaboration with Gwee on Pileh Menantu, has consulted him for various details regarding Peranakan customs, language and music for his subsequent Peranakan productions.9

Gwee’s songs are written in a style typical of 1950s Peranakan performances, with sentimental melodies often set to joget or other dance rhythms. They usually revolve around Peranakan culture as well as love and courtship. Some of the more popular ones are Nasi Ulam, Baju Panjang, and Di Kebun Bunga. Stylistically, many of these songs retain traditional melodies and sounds that would have been heard during his parents’ generation — likely the result of Gwee’s early exposure to such music at home.

Gwee stayed mostly out of the limelight throughout his life. His influence is felt more as a mentor and consultant to a few younger Peranakans who have gone on to produce shows. Richard Tan took a more modern step with Bibiks Behind Bars in 2002 and Bibiks go Broadway in 2003. Later, Tan founded the theatre company Main Wayang, mounting modern stagings of Peranakan shows. He has also recorded four CD albums of original Peranakan songs, many of which were written by Gwee.10 Another collaborator who benefitted from Gwee’s mentorship is Alvin Oon, who was a director and performer with Main Wayang and eventually left to form the performing arts group Peranakan Sayang. Oon’s productions are typically modern in conception and aim to connect with and educate younger Peranakans who are not so fluent in the Baba language or customs. He has used technology to create an internet presence for his shows, which were watched by many during the COVID-19 pandemic.11

It is clear that Gwee’s love for the Peranakan culture runs deep. As a storyteller, lexicographer, historian, playwright, songwriter, consultant and mentor, his work preserves precious memories and offers people a glimpse into a world and time long past. He has done much for the preservation and recognition of Peranakan culture, both for people within the community as well as those outside of it.

| 1 | This essay is based on the author’s interviews with Alvin Oon on 26 June 2024 and Richard Tan on 6 July 2024. |

| 2 | Gwee William Thian Hock, oral history interviews, 21 April 1986, National Archives of Singapore, Reel/Disc 1–30. |

| 3 | “G. T. Lye: Providing a Window into Peranakan Culture Stewards of Intangible Cultural Heritage Award 2020 Recipient,” National Heritage Board’s Roots. |

| 4 | Today’s Kuo Chuan Presbyterian Primary School and Kuo Chuan Presbyterian Secondary School. |

| 5 | “Surviving the Second World War in Singapore,” The New Paper, 1 September 2016. |

| 6 | Gwee’s extensive knowledge and contributions was even acknowledged by a letter to the Peranakan Association by renowned anthropologist Professor Tan Chee Beng that was published in the December 1995 edition of the newsletter. |

| 7 | Baba plays produced during and before Gwee’s time tend to involve a mix of spoken word, song and dance. The songs are often set to pantuns in the Baba patois, and use elements of music similar to Malay Bangsawan plays of the same period. |

| 8 | Ng Fooi Beng, “Xinma baba wenxue de yanjiu” [A Study of Baba Literature in Singapore and Malaysia] (MA thesis, National Chengchi University, 2003). |

| 9 | Interview with Richard Tan, 6 July 2024. |

| 10 | Interview with Richard Tan, 6 July 2024. |

| 11 | Interview with Alvin Oon, 26 June 2024. |

“House Visit — An Afternoon with the Gwee Family.” Singapore: Singapore Heritage Society website, 28 August 2014. | |

“And the music plays on.” Bukit Brown Cemetery: Our Roots, Our Future, online blog, 6 May 2012. | |

“ T. Lye: Providing a Window into Peranakan Culture.” National Heritage Board’s Roots. | |

Gwee, Thian Hock. A Nonya Mosaic: My Mother’s Childhood. Singapore: Times Books International, 1985. | |

Gwee, Thian Hock. A Baba boyhood: Growing up during World War 2. Singapore: Marshall Cavendish Editions, 2013. | |

Gwee William Thian Hock, oral history interview by Dr Daniel Chew, 21 April 1986, transcript and audio, National Archives of Singapore (accession n 000658), Reel/Disc 1–30. | |

Gwee, Thian Hock. “The Singapore Chinese Mandarin School and Its Baba Connection.” THE PERANAKAN, 18 September 2023. | |

Ng, Fooi Beng. “Xinma baba wenxue de yanjiu” [A Study of Baba Literature in Singapore and Malaysia]. MA thesis, National Chengchi University, 2003. | |

Swaminathan, Shruthi. “Surviving the Second World War in Singapore.” The New Paper, 15 February 2017. |