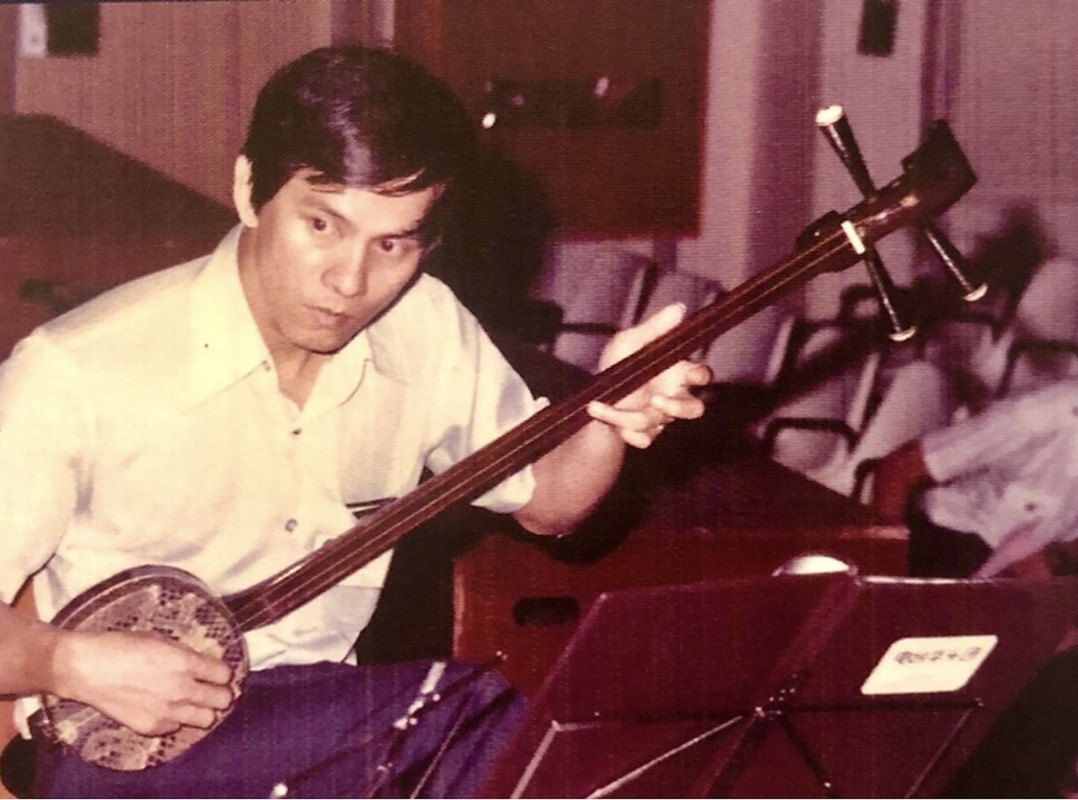

Singapore’s early Chinese musicians

Singapore’s early Chinese musicians include immigrants who came to Singapore in the 19th century, the country’s Pioneer Generation (those born in 1949 or earlier), as well as the subsequent local-born generation.

Some of these early musicians were folk musicians with no formal musical training, and their musical performances were a common feature of Singapore’s historical soundscape. Others were formally-trained composers and performers who blended what they had learnt with local elements. Together with the emerging nation of Singapore, these early Chinese musicians navigated different cultural milieus and kept local Chinese music alive, resulting in diverse expressions of Singapore Chinese music through the different eras. Just as Singapore’s pioneers in various fields created a unique Singapore, Chinese musicians in post-independence Singapore began to seek a musical identity and create diverse styles of music that were distinctly Singaporean.

Singapore’s early Chinese musicians can be categorised into traditional dialect-based genres, and pan-Chinese genres (e.g. Chinese orchestra music, English pop music). Early musicians who belonged to the pan-Chinese category were trained under the Western classical music education system and used similar methods to teach the next generation of musicians or compose musical works.

Musicians can also be broadly grouped into two categories based on where they were trained — the first being the Chinese world such as China, Hong Kong, and Taiwan, and the second encompassing Europe and the United States. Each music genre boasts numerous important pioneer Chinese musicians who contributed significantly to their fields.

Dialect-based music genres

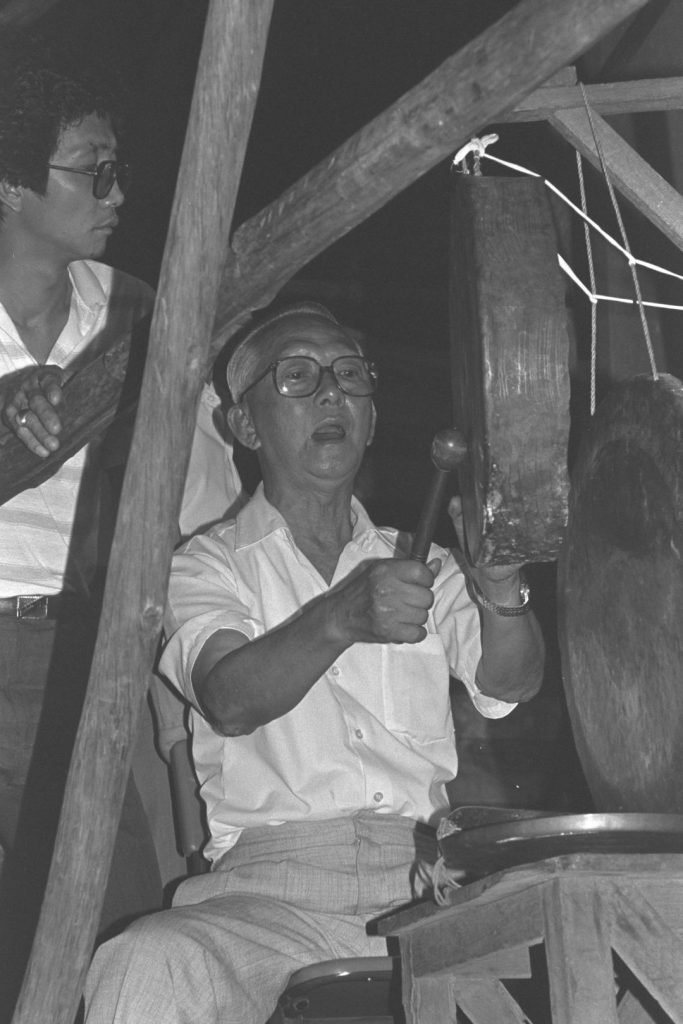

Most of the early Chinese musicians in dialect-based music genres were exposed to traditional music by chance. In the early days, few could afford to spend on entertainment. Watching street operas performed for the deities was the main form of entertainment, as well as a channel for these musicians to be exposed to dialect-based music. Most male musicians, after receiving their degrees and becoming successful in their respective professions, continued to participate in traditional music activities outside of work. Female musicians, meanwhile, juggled family commitments while setting up societies and troupes to promote the traditional music that they were passionate about.

Before the establishment of diplomatic relations between Singapore and China, most Chinese dialect-based musicians not only promoted music activities in Singapore, but also travelled to Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Southeast Asia to perform and interact with musicians there. After Singapore and China established formal diplomatic relations in 1990, early Chinese musicians visited China to explore the birthplaces of the traditional music of various dialect groups. Through such exchanges, these musicians began to think about and introduce reforms in traditional music, switching from traditional oral methods of teaching to setting up professional training classes, using sheet music, as well as coming up with new songs and librettos. They refined Chinese opera performances, moving from shows primarily for entertainment at Chinese temples to more sophisticated stage performances that emphasised refined visual and auditory effects. They also engaged the community to garner their support, and initiated fundraising activities among business associations, clan associations, and banks to obtain stable and adequate funding. These efforts allowed traditional music to be not just passed down, but also gain international recognition.

East meets West: Pan-Chinese genres

Some early Chinese musicians in pan-Chinese music genres who came from China and Hong Kong were professionally trained in music, with many having studied at prestigious Chinese music colleges under renowned Chinese musicians or Russian educators who had gone to China. After they came to Singapore, they taught at schools under the Ministry of Education, while still following the development of music in China and striving to bring musical resources to Singapore.

Other pan-Chinese musicians were born and bred Singaporeans, many of whom had furthered their music education in the United Kingdom, Europe, or the United States after completing basic education in Singapore. Their work reflected their affection for Singapore and often portrayed the hardships of the older days. After graduating and returning to Singapore, these Western-trained musicians maintained ties with Europe and the United States and often travelled there for further studies. The style of their works was clearly different from those who trained only in China. Compared to their dialect-based counterparts, musicians of pan-Chinese music genres offered a more globalised vision of Singapore, taking advantage of Western music resources and blending Western and local styles to create new musical horizons.

Singapore’s early Chinese musicians were instrumental to the growth and development of Singaporean music, laying a foundation for the local music scene. They discovered and nurtured talent, allowing Singapore, once perceived as a cultural desert, to slowly be acknowledged by the world for its artistic output. The emergence of a unique Singaporean music style reflects not only the localisation of dialect-based music genres which the immigrants had brought with them, but also the influence of Western classical music in Southeast Asia.

Pioneer Chinese musicians featured in Culturepaedia

(List to be progressively updated)

| Dialect-based music genres | Pan-Chinese music genres |

| Teng Mah Seng | Lee Howe |

| Han Yin Juan | Leong Yoon Pin |

| Lian Yoong Ser | Shen Ping Kwang |

| Joanna Wong | Michael Tien Ming Ern |

| Chee Kin Foon | Samuel Ting Chu-San |

| Goh Swee Meng | Tay Teow Kiat |

| William Gwee Thian Hock |

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡华人早期音乐家. Click here to read original piece.

Chia, Wei Khuan. “Xinjiapo de huawen hechang huodong” [Chinese choral activities in Singapore]. In Fujian yishu [Fujian Art], no. 5 (2006): 50–51. | |

Dairianathan, Eugene and Phan, Ming Yen. “A narrative history of music in Singapore 1819 to the present.” Technical report submitted to the National Arts Council, Singapore, 2002. | |

Goh, Ek Meng. Xinjiapo huayue fazhan shilue, 1953 nian zhi 1979 nian [A history of the development of Chinese music in Singapore, 1953–1979]. Singapore: Lingzi Media, 1998. | |

Goh, Keng Leng. Yinyuejia zhuanji [Musicians’ biography]. Singapore: Seng Yew Book Store, 1987. | |

Hsu, Tsang-Houei. “Taiwan, xin, ma zuoqujie de bozhongzhe: Shen Bingguang laoshi” [Planting seeds for the composers’ community in Taiwan, Singapore and Malaysia]. In Shenbingguang zhi ge [The songs of Shen Ping Kwang], edited by Shen Ping Kwang, 3. Singapore: Seng Yew Book Store, 1990. | |

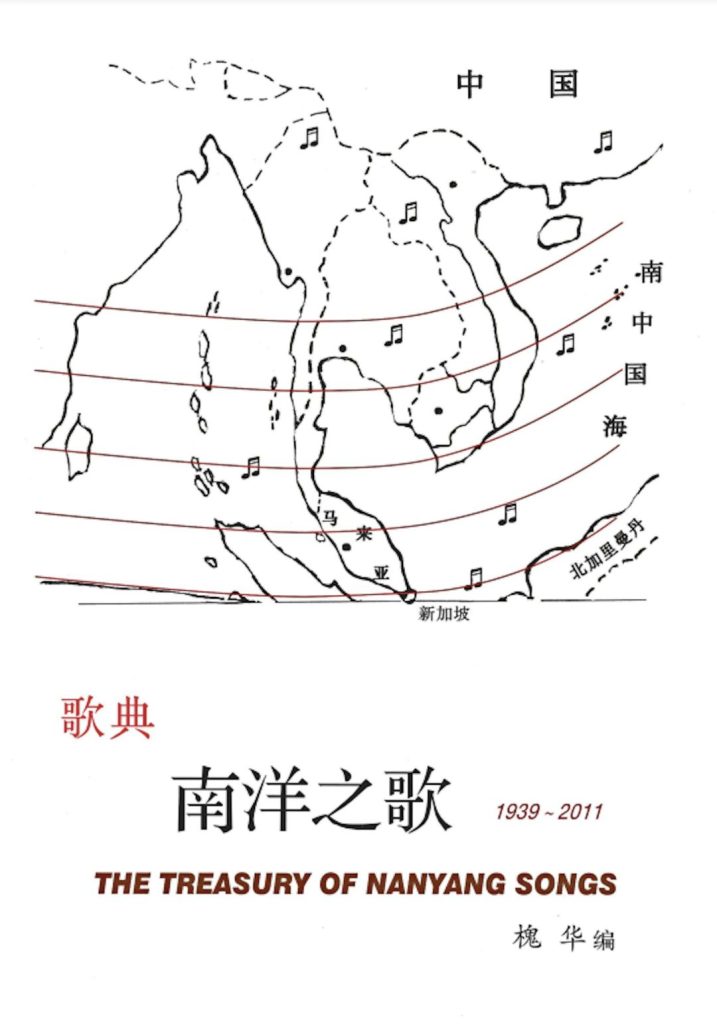

Huai, Hua, ed. Gedian: nanyang zhi ge, 1939–2011 [The treasury of Nanyang songs, 1939–2011]. Singapore: Zhaohui Arts and Culture Publishing, 2013. | |

Leong, Weng Kam. Renmin de yuetuan: xinjiapo huayuetuan 1996–2016 [The people’s orchestra: Singapore Chinese Orchestra 1996–2016]. Singapore: Singapore Chinese Orchestra Company Limited, 2017. | |

Ling, Hock Siang. Shiyu xia de xinjiapo huayue fazhan lujing [Overview of the development of Singapore Chinese music]. Singapore: Singapore Chinese Music Federation, 2023. | |

National Theatre Composers’ Circle, ed. Xinjiapo gequ chuangzuo [Songwriting in Singapore], vol. 2. Singapore: National Theatre Composers’ Circle and Seng Yew Book Store, 1986. | |

People’s Action Party Central Cultural Bureau, ed. Xinjiapo song: bendi chuangzuo yuequ xuanji [Ode to Singapore: A selection of local compositions]. Singapore: People’s Action Party Central Cultural Bureau, 1968. | |

Tu, Ching, ed. Jiaolin women de muqin: yi ge yinyuejia jiannan de xuexi lucheng [Rubber plantations, our Mother: The hardships of a musician in his journey of learning]. Singapore: Global World Scientific Publishing, 2009. | |

Wang, Yonghong and Lin, Cixun, eds. Nanyang zhi ge xuji: qishi niandai bendi chuangzuo geji [Nanyang songbook 2: A collection of local compositions from the 1970s]. Singapore: Self-published, 2019. | |

Wong, Chee Meng. Youying zhen tiansheng: niucheshui bainian wenhua licheng [A century of Singapore’s Chinatown in cultural and historical memory]. Singapore: Global Publishing, 2019. | |

Wong, Chin Soon. Shuo liyuan hua getai [About Liyuan and getai]. Singapore: Hainanese Cultural Society of Singapore, 2015. | |

Yi, Yan. Liyuan shiji: xinjiapo huazu difang xiqu zhi lu [Hundred years development of Singapore Chinese opera]. Singapore: The Singapore Chinese Opera Institute, 2015. |