The evolution of Chinese hawkers and hawker culture in Singapore

Hawker food and hawker culture are core parts of the Singaporean identity. As members of a relatively young nation shaped by diverse cultural influences, Singaporeans are known not just for their love for hunting the best hawker food but also the queues they will endure to get it. Although hawker culture has gained tremendous international recognition in recent years, it is a lesser-known fact that Singapore is one of the few countries (if not the only) to develop hawker centres — sheltered, intentionally multicultural spaces where hawker food is produced and consumed.1 Seen by many as vibrant and communal dining spaces now, hawker centres were in fact first developed as a highly specific urban engineering solution by the government in the early 1970s to address chronic street hawking issues and formalise street hawking. In this light, the history of hawker centres, and hawking more broadly, mirrors Singapore’s socioeconomic evolution, revealing glimpses of the nation’s wider past and development over time.

Hawking in colonial Singapore

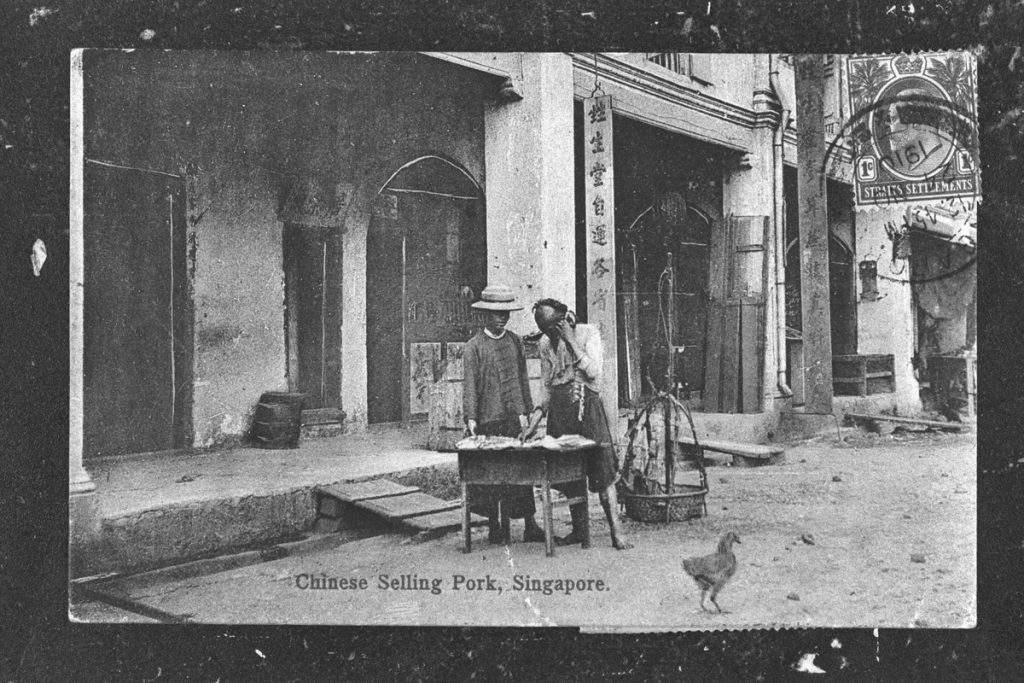

The roots of modern Singapore’s hawker culture can be traced back to colonial times in the 1800s. As a growing British trading port, Singapore attracted waves of immigrants from China, India, and the Nusantara seeking better opportunities.2 Rapid population growth and urbanisation fuelled the rise of hawking. Despite Singapore’s expanding economy, economic disparities and frictional or structural employment left many without stable employment, leading these individuals to turn to alternative (albeit transient) means of income. With low barriers to entry and a potential for a decent income, hawking was one of the most attractive options.

The appeal of hawking was further reinforced by a strong demand for cooked food services. Many labourers were solitary male migrants who lacked the means — time as well as economic and supporting social structures (e.g. family) — to cook for themselves.3 As a result, many labourers relied on cooked food hawkers for affordable and convenient meals. Demand was especially high on working days when hawkers would congregate at docks and office areas to sell lunch to coolies, clerks, and messengers.

Characteristics and distribution of Chinese hawkers in pre-independence Singapore

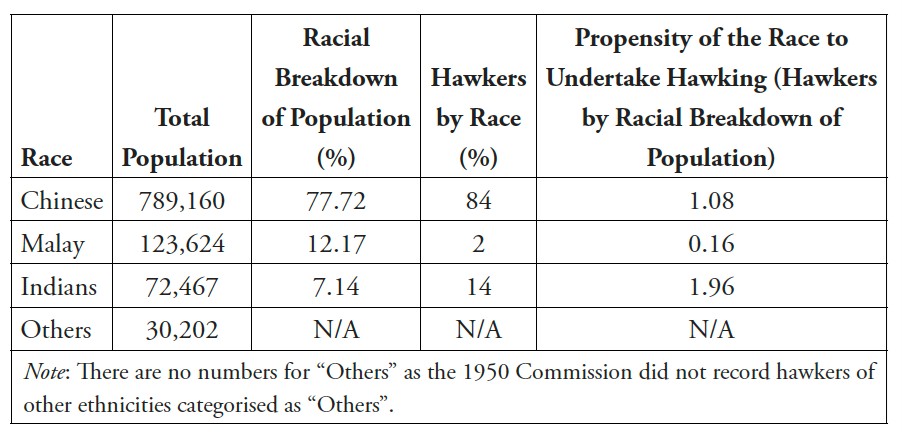

In terms of absolute numbers, the hawking trade was (and still is) dominated by the Chinese, with its boons and banes largely attributable to the community. This was even more so during the pre-independence period, when a survey conducted by the 1950 Hawkers Inquiry Commission reported that 84% of hawkers were Chinese, with Indians the next largest group at 14%. Compared with the ethnic composition of Singapore’s population at that time, it was evident that immigrants (primarily Chinese and Indians) formed the bulk of the early hawker population. The dominance of Chinese hawkers was so pronounced that the 1950 Commission referred to hawking as a “Chinese problem”, attributed to “the desire of the ordinary man to work on his own account and be his own master”.4

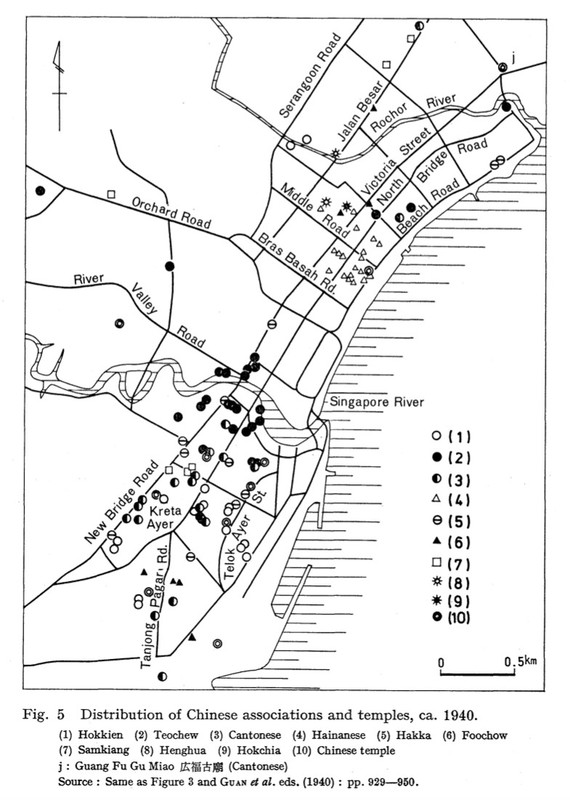

Hawkers typically clustered in two key areas: business districts, where they catered to labourers; and ethnic- or dialect-based neighbourhoods, which were often their residential communities.5 During this period, Singapore was organised in ethnic enclaves — Chinatown for the Chinese, Kampong Glam for the Malays, and Little India for the Indians. The Chinese community was further segmented by dialect groups. Major dialect groups like the Hokkiens, Teochews, and Cantonese settled south of the Singapore River, while smaller groups like the Hainanese and Foochow lived on the north bank.6 It was likely that beyond working days, hawkers would serve their fare around their own enclaves, offering familiar flavours from home.

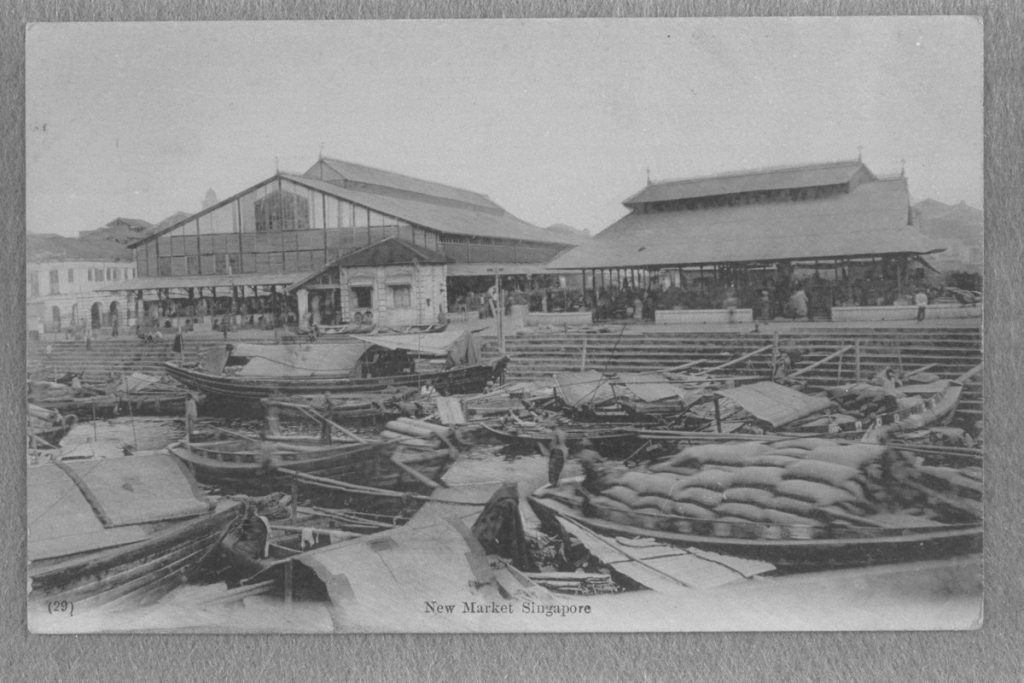

A notable example is Ellenborough Market, constructed in 1845 on the south bank of the Singapore River. Also known as Teochew Market or Pasar Bahru (New Market), it was a wet market renowned for its Teochew goods, including fresh fish, dried seafood, and ingredients commonly used in Teochew cuisine. It is likely that Teochew hawkers would have clustered around the market, selling traditional Teochew dishes to fellow shoppers.

Problems and regulation of the hawking trade

Unregulated and itinerant hawking brought numerous challenges to the municipal authorities, primarily related to urban pollution and public health concerns. These issues were so severe that in 1913, W.R.C. Middleton (birth and death years unknown), a municipal health officer, described them as “evils” — citing the obstruction of streets and five-foot ways, and the selling of unhygienic food.7

First, hawkers posed significant challenges to urban integrity and planning. Large numbers of itinerant hawkers would cluster in high-traffic areas in an unpredictable manner, causing congestion for vehicles and pedestrians. This was especially pronounced in the Central Business District (Raffles Square and Collyer Quay) and at the docks, where workers and businesses were concentrated. Second, food preparation practices were often unsanitary. Hawkers frequently used contaminated water sources for cooking and washing. They also disposed of food waste in drains, clogging the proper sanitary channels. These practices posed serious public health risks, contributing to outbreaks of cholera and typhoid, and encouraging the spread of pests and rodents.

Early attempts to address these issues and regulate hawkers began in 1903, when the Chinese Protectorate introduced voluntary hawker registration for Chinese hawkers. It is worth noting that these early attempts at hawker legislation lacked British support, as colonial authorities were reluctant to allocate resources for licensing and enforcement. However, due to the growing scale of hawker-related issues, the British authorities took over hawker regulation in 1907 and introduced the first by-laws aimed at registering and regulating night hawkers. These by-laws were largely ineffective as they applied only to night hawkers, which constituted a small fraction of the hawker population. In 1919, the law was expanded to include both day and night hawkers. These legislative changes, however, were more bark than bite, as the authorities did not have sufficient bureaucratic capacity to enforce said legislation and regulate the hawking trade effectively.

Hawker reform and hawker centres

Following Singapore’s independence in 1965, Lee Kuan Yew (1923–2015) and the founding leaders enacted extensive political, economic, and social reforms. These reforms extended to the hawker industry, which underwent significant restructuring between the late 1960s and 1970s. Between 1969 and 1973, a series of policies, collectively referred to as “Hawker Reform”, were introduced to address public health concerns and urban pollution caused by unregulated hawking.8

Singapore’s hawker reform revolved around three key strategies. The first was the introduction of legislation such as the 1969 Environmental Public Health Act (EPHA) and the 1973 Sale of Food Act. These laws not only established legally binding hygiene standards, but also established a framework for hawker governance and operations. Further, the EPHA empowered non-police health officers to punish hawkers for their infractions directly, speeding up the process of enforcement and corrective action.

The second was the reorganisation and expansion of the Hawkers Department (HD) within the then-Ministry of Environment. Between 1965 and 1973, the HD engaged in organisational capacity building to develop its planning and enforcement capabilities, setting up specialised departments to oversee long-term planning and strategy — including the planning of permanent hawker shelters (hawker centres) that would eventually come to house hawkers — and almost tripling the number of public health enforcement offers. These changes allowed the government to better oversee the effective development and enforcement of hawker policy.

The third and most salient aspect of the hawker reform was the mandatory hawker relocation to hawker centres. Through the late 1960s and 1970s, street hawkers were systematically relocated to government-constructed shelters which provided essential sanitation facilities and prevented the uncontrolled clustering of hawkers on public streets. By 1973, the Ministry of Environment had constructed 15 hawker centres, with plans to build 25 to 30 more annually until 1976. This relocation policy not only permanently improved hygiene standards but also moved hawkers off the streets, formalising the hawker trade to what it is today.

The introduction of hawker centres reshaped the ethnic distribution of hawkers. As hawker centres were strategically located to serve residents in public housing estates built by the Housing and Development Board (HDB), the hawker centre became a neutral space in an engineered environment. The introduction of the Ethnic Integration Policy (EIP) in 1989 ensured that public housing reflected Singapore’s racial demographics — approximately 75% Chinese, 15% Malay, 8% Indian, and 2% “Others” — with hawker centres similarly following suit. Till today, hawker centres cater to this racially re-balanced population via licence quotas for various food types (e.g. Chinese, Malay, Indian). Unlike during the colonial era, when the hawker trade was concentrated in ethnic enclaves and disproportionately dominated by the Chinese and Indian communities, these reforms aligned hawker distribution with Singapore’s multicultural policies, fostering inclusivity across communities and maintaining accessibility for all. Today, hawker culture is a celebrated jewel of Singapore’s heritage, a reflection of the nation’s history, diversity, and traditions.

| 1 | Ryan Kueh, From Streets to Stalls: The History and Evolution of Hawking and Hawker Centres in Singapore. |

| 2 | Nusantara refers to a historical region influenced by Indonesian and Malay cultures. It once encompassed kingdoms like Sri Vijaya, Majapahit, and Johor-Riau, covering areas that are now Indonesia, Singapore, Brunei, southern Thailand, and parts of the Philippines. Refer to Timothy P. Barnard, ed. Contesting Malayness: Malay Identity Across Boundaries (Singapore: Singapore University Press, 2004). |

| 3 | Kueh, From Streets to Stalls. |

| 4 | Hawkers Inquiry Commission, “Report of the Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950.” |

| 5 | Kueh, From Streets to Stalls. |

| 6 | Kiyomi Yamashita, “The Residential Segregation of Chinese Dialect Groups in Singapore: With Focus on the Period before ca. 1970,” Geographical Review of Japan 59 (Ser. B), no. 2 (1986): 90. |

| 7 | W. Bartley, “Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Hawker Question in Singapore,” Colonial Secretary Singapore, 4 November 1931, 8. |

| 8 | Kueh, From Streets to Stalls. |

Bartley, W. Report of the Committee Appointed to Investigate the Hawker Question in Singapore. Colonial Secretary Singapore, 4 November 1931. | |

Hawkers Inquiry Commission. “Report of the Hawkers Inquiry Commission, 1950.” Colony of Singapore, 30 September 1950. | |

Kueh, Ryan. From Streets to Stalls: The History and Evolution of Hawking and Hawker Centres in Singapore. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co, 2024. | |

Yamashita, Kiyomi. “The Residential Segregation of Chinese Dialect Groups in Singapore: With Focus on the Period before ca. 1970.” Geographical Review of Japan 59 (Ser. B), no. 2 (1986): 83–102. |