Calligraphy at Chinese temples in Singapore

When building temples, the Chinese have always attached great importance to the stelae and plaques installed in, and couplets engraved on the pillars of, these temples. Most of the calligraphy on these artefacts were written by distinguished masters.1 The inscriptions on the stelae eulogise achievements and virtues, as well as expound the history of the temples or contain information on the donors of the temples. The plaques and couplets not only beautify the temples and their environment but also serve to enlighten the public.2

Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery

Two stone pillars at each side of the main door along the central axis of Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery are engraved with a seven-character couplet by local calligrapher Koh Mun Hong, which reads “fan yin shang che san qian jie, fa zang zong han ba wan men” (the sound of Sanskrit penetrates the universe, and within Dharma lies 80,000 gates). Once inside the temple, one is greeted by a plaque with the words “tian wang dian” (Hall of the Celestial Kings), erected in 1906 by the temple’s founder Low Kim Pong (1838–1909). The Hall of the Celestial Kings is flanked by two stone pillars engraved with an 11-character couplet in 1905. It reads “yi shui ying hui shu se cang mang lan ruo jing, wan shan huan rao zhong sheng tiao di bai yun shen” (the temple stands in tranquility amidst the lingering water and vast trees, and the sound of bells transcends the surrounding mountains to reach deep in the white clouds). Such words serve to remind a worshipper or visitor of how this century-old temple used to be a peaceful retreat away from the hustle and bustle, where monks, with oil lamps and old statues of Buddha as companions, led a very different life from the secular world.

A plaque in the main Mahavira Hall bearing the four characters “da xiong bao dian” written in the regular script was also installed by Low. Within the Mahavira Hall stands a stone pillar engraved with a 17-character couplet written in the clerical script by Khoo Seok Wan (1874–1941). It reads “guang duo heng xing, xian kong ye hui yi qian qiu dong ya wei si zhou sheng; zong chuan xiang jiao, he fo fa seng zhi san bao xi zhu cheng yi jia yan” (Buddhism endures in brilliance and spirit, with deep roots and lasting influence across time and cultures). On the right hand side of the Mahavira Hall is the “zhai tang” (dining hall), with a plaque bearing the inscription of the two characters written by calligrapher Lu Yiyan (1928–2007) from Zhongshan, Guangdong. A stone pillar in front of the dining hall, erected by Venerable Ming Guang (birth and death years unknown) in 1905, is engraved with a seven-character couplet in regular script, which reads “wu yan yuan ming jin yi hua, san xin wei liao shui nan xiao” (if the Five Contemplations are fully practiced, even gold is easily consumed, shall the Three Minds remain unaware, even water becomes indigestible), written by the Venerable himself.3 The “cang jing lou” (sutra library) at the back of the temple bears a plaque with the three characters written by Zhao Puchu (1907–2000), a leader of the Buddhist community in China.

Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery

The century-old Kong Meng San Phor Kark See Monastery houses two plaques, with writings by Wu Weiruo (1900–1980), and the other by Zheng Yusheng (birth and death years unknown) in 1926 as a gift to the monastery. The writings in both plaques are in regular script, and Wu’s strokes were fuller while those of Zheng were slightly hollow and more forceful.4 In addition, the two plaques at the “da bei dian” (Hall of Great Compassion) and sutra library were also inscribed by Zhao Pucu.5

Chian Pok Ee

The local monastery with the largest collection of writings by Chinese monks, literati, politicians, calligraphers and artists is Chian Pok Ee.6 After the passing of Venerable Kong Hiap (1900–1994) who used to helm Chian Pok Ee, Singapore Buddhist Lodge took over its management, and renamed it Kong Hiap Memorial Museum in 2007. Its Chinese name “zhan bo yuan” inscribed on the plaque at the main gate was written by Venerable Hong Yi (1880–1942), while the plaque in the main hall bears the writings of renowned Chinese painter Feng Zikai (1898–1975). All in all, the museum has the largest collection of writings by Venerable Hong Yi and Feng Zikai in Singapore. Venerable Kong Hiap also published a collection of letters between him and Feng Zikai, as well as calligraphic works that Chinese poet Ma Yifu (1883–1967) gifted him,7 which serve as excellent models for calligraphy enthusiasts. Chian Pok Ee itself can be considered a small museum of artefacts.

In addition, the Leng Foong Prajna Temple, which used to be the Singapore Girls’ Buddhist Institute, also houses a number of plaques with writings by distinguished masters. Two plaques in the dining hall have writings of Venerable Song Nian (1911–1997) done in his younger days, which differ from his calligraphic works in his later years in terms of style.8 The Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society established in 1995, also has a large collection of calligraphic works by venerable monks, which are not usually seen by others.9 While it is not the main job of monks and nuns to engage in calligraphy and painting, it is also a good thing if they can connect with the world through calligraphy as Venerable Hong Yi did, as it would guide people to be kind, as well as promote the teaching of Buddhism for the benefit of mankind.

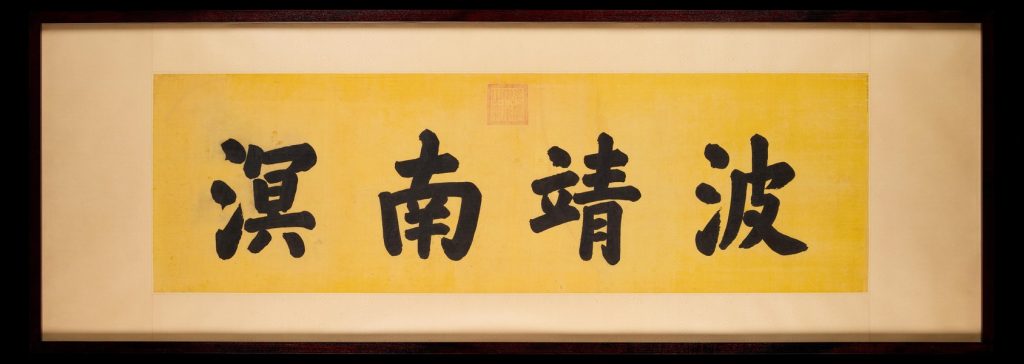

Thian Hock Keng

Generally speaking, calligraphy in local Taoist temples that are over 150 years old are mainly in the form of inscriptions on stelae, plaques and couplets. Thian Hock Keng, a temple located at Telok Ayer Street, was built by early Hokkien immigrants to worship Mazu, the god of the seas.10 The most talked-about feature of the temple is an imperial scroll bearing the characters “bo jing nan ming” (calm waves on the south seas) written by Emperor Guangxu (1871–1908).11 The temple today still features many plaques and stelae,12 which are important materials for the study of the social history of Chinese in Singapore and Malaysia.13 On the other hand, the Yueh Hai Ching Temple near Raffles Place MRT was built by the Teochews. It consists of two shrines — the shrine of Tian Hou (the Mother of Heavenly Sages, which is Mazu) and the shrine of Xuan Tian Shang Di (the Heavenly Emperor), which joined to form one temple. It features a couplet engraved in 1826, showing that the temple was built earlier than Thian Hock Keng.14Yueh Hai Ching Temple also features a plaque with the characters “shu hai xiang yun” (auspicious cloud above the sea at dawn) written by Emperor Guangxu. It was installed in 1899, when the temple raised funds for flood victims in Guangdong, and was bestowed with the commendation plaque by the Qing court.15

The Fuk Tak Chi temple near Far East Square was built by Cantonese and Hakka immigrants, and is also one of the oldest Chinese temples in Singapore. The temple was renovated by Cheang Hong Lim (1825–1893) in 1869, and today, it is part of a boutique hotel. The Fuk Tak Chi Museum still houses many plaques, with the earliest plague bearing the words “lai ji xia zou” (bliss is everywhere) erected in 1824. The latest plaque was installed in 1918, with the characters “bao you li min” (bless the people). Plaques that still remain in Fuk Tak Chi temple, which is dedicated to deity Tua Pek Kong, mainly bear prayers for blessings from the heavens, reflecting the people’s wishes for the deities to grant them safety, favourable weather and a good life.

In a nutshell, stelae and plaques in Chinese temples are more than just ordinary artefacts. They not only carry the beliefs of early Chinese immigrants and their sentiments towards their host countries which allowed them to earn a living and live in peace, but also serve as important links to traditions and culture.

This is an edited and translated version of 新加坡华族寺庙的书迹. Click here to read original piece.

| 1 | For example, the plaque at the main gate of Hai Inn Temple in Chua Chu Kang bears the characters “hai yin gu si” (Hai Inn old temple) written by Venerable Sheng Yan (1931–2009), while the name of the temple “hai yin si” on a plaque displayed at the main hall was written by Xu Beihong (1895–1953). The couplet at the entrance of the main hall of the old building of Poh Ming Tse in Bukit Timah was written by Venerable Tai Xu (1890–1947). |

| 2 | In the 1970s and 1980s, when passing by the Fa Hua Monastery at Paya Lebar Road, no one would not miss the eight characters “zhu e mo zuo, zhong shan feng xing” (Do no evil, perform good deeds) engraved on the exterior wall of the monastery. |

| 3 | The dining hall of Lian Shan Shuang Lin Monastery also displays a plaque bearing three characters “wu guan tang” (five contemplations hall) written by Venerable Long Gen (1921–2011), while its wall is adorned with a pair of eight-character couplet in regular script by Beijing calligrapher Wang Zhilin, which reads “dian yu wei e zhuang yan san bao, yan xia ai rui yu xiu shuang lin” (lofty and dignified halls with the presence of Buddha, Dhama and Sangha, and beautiful Shuang Lin veiled in an auspicious mist). |

| 4 | See local calligrapher Soon Chin Tuan’s blog: Chin Tuan’s Calligraphy World, February 2013. |

| 5 | See local calligrapher Soon Chin Tuan’s blog: Chin Tuan’s Calligraphy World, February 2013. |

| 6 | An album published by Kong Hiap Memorial Museum features calligraphic works and paintings by Venerable Master Yinguang, Ye Gongchuo, Qi Baishi, Xu Beihong, Ma Yifu, Yu Youren, Yu Dafu, Ye Shengtao, Tang Yun and Sha Menghai. |

| 7 | Venerable Kong Hiap ed, Fengzikai zhi guangqia fashi shuxinxuan [Selected letters from Feng Zikai to Venerable Kong Hiap]; Ma Yifu, Sengcan dashi xinxinming [Faith in mind by Seng Ts’an] and shitouqian chanshi cantongqi·yunyan baojing sanmei [Dhyana Master Xiqian’s harmony of difference and sameness·Yun Yen’s gatha on the precious mirror samadhi]. |

| 8 | Two plaques in the dining hall at the back of the temple were written by Venerable Song Nian, bearing characters “guang pi yan fu” (light shines on the world) and “fu cheng zai xian” (The blessed city rises again) respectively. They were written to celebrate the completion of the Leng Foong Prajna Temple. The inscription also indicated the year as 1968. Plaques displayed at the second storey of the temple include one by Hong Kong calligrapher Wu Tianren and several others by anonymous calligraphers. |

| 9 | Lingxin moji: yaoshi xingyuanhui shuhua zuopinji [A collection of calligraphic works and paintings] published by the Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society features writings of senior monks such as Master Yin Shun, Venerable Zhu Mo, Venerable Song Nian, Venerable Bo Yuan, Venerable Zhen Chan, Venerable Long Gen, Venerable Chang Kai, Venerable Beow Teng and Venerable Chao Chen. |

| 10 | Lim How Seng et al, Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat], 50. A 21-character couplet hangs at the main hall of Thian Hock Keng, which translates into “Singapore is the first port of disembarkation for early Chinese immigrants, who would visit Thian Hock Keng to thank the sea goddess Mazu for a safe journey, and that building the Mazu temple was to allow Mazu to meet old friends who were deities from three mountains”. Such a description is enough for the future generations to imagine the vast number of ships plying the seas here in the past, and the risks faced by immigrants at sea when they left China and travelled south. |

| 11 | Zhang Xiaozhai, From Ashes to Treasures: My 60 Years of Restoring Chinese Art, trans. Michelle Lee, 103–116. |

| 12 | For example, the plaque at the entrance of the main hall bearing the characters “xian che you ming” (clear and bright) was erected by China’s first consul to Singapore Zuo Binglong (1850–1924), while the plaque within the main hall which reads “ze pi gong fu” (blessings for all and splendid achievements) was erected by Chinese community leader Tan Tock Seng (1798–1850). |

| 13 | Lim How Seng et al, Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat], 49–52. |

| 14 | Lim How Seng et al, Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat], 147–148. |

| 15 | Lim How Seng et al, Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat], 149. |

Kong Hiap Memorial Museum Picture Album. Singapore: Kong Hiap Memorial Museum, 2007. | |

Ma, Yifu. Sengcan dashi xinxinming [Faith in mind by Seng Ts’an] and shitouqian chanshi cantongqi, yunyan baojing sanmei [Dhyana Master Xiqian’s harmony of difference and sameness, Yun Yen’s gatha on the precious mirror samadhi]. Singapore: Chian Pok Ee, 1986. | |

Zhang, Xiaozhai. From Ashes to Treasures: My 60 Years of Restoring Chinese Art. Translated by Michelle Lee. Singapore: Wen Bao Zhai, 2025. | |

Lim, How Seng et al. Shile guji [Historical Monuments in Silat]. Singapore: South Seas Society, 1975. | |

Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society, ed. Lingxin moji: yaoshi xingyuanhui shuhua zuopinji [A collection of calligraphic works and paintings]. Singapore: Buddha of Medicine Welfare Society, 2024. | |

Venerable Kong Hiap, ed. Fengzikai zhi guangqia fashi shuxinxuan [Selected letters from Feng Zikai to Venerable Kong Hiap]. Singapore: Chian Pok Ee, 1977. |