Pioneer artist: Lim Tze Peng

Among Singapore’s home-grown artists, Lim Tze Peng (1921–2025) had a remarkably long and impressive career. Although he had never attended a formal art school and was a self-taught artist, he received much critical and commercial acclaim for his Chinese calligraphy and paintings in ink and oil.

Early life

Born in 1921 in Singapore, Lim had humble beginnings. His China-born parents were uneducated and eked a living by growing crops and rearing animals in a village in Pasir Ris.1 Lim’s early interest in art was nurtured by encouraging teachers. In primary school, he picked up ink painting and calligraphy.2 In Chinese High School, art teacher Lu Heng (1902–1961) taught drawing and watercolour painting, and brought students for outdoor painting during the weekends.3 Later, when Lim enrolled at Chung Cheng High School due to its more affordable fees, his proficiency in art was further enhanced by influential teachers such as Wong Jai Ling (1895–1973), Yeh Chi Wei (1913–1981) and Liu Kang (1911–2004), who were born and trained in China.4 Wong gave Lim personal lessons in calligraphy, teaching him how to hold the brush and the importance of using stele rubbings (beitie) as models of writing. Liu introduced Lim to oil painting, while Yeh continued to emphasise the importance of outdoor painting.

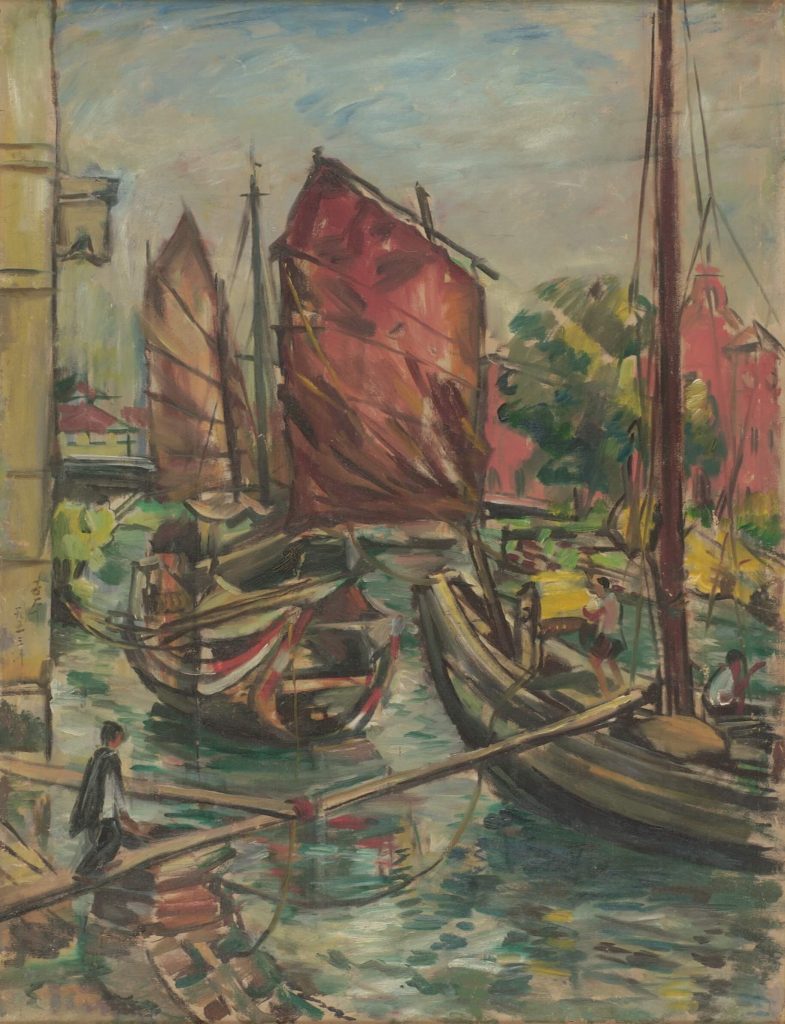

After graduating in 1948, Lim spent the next three decades working as a primary school principal while his wife supplemented the family’s livelihood by working on their farm. Despite his busy schedule, Lim continued to write calligraphy and paint in his free time. He also taught students who were interested in art, and brought them out for painting sessions.5 Chinese Junks (1953) is a typical oil painting by Lim from the 1950s.

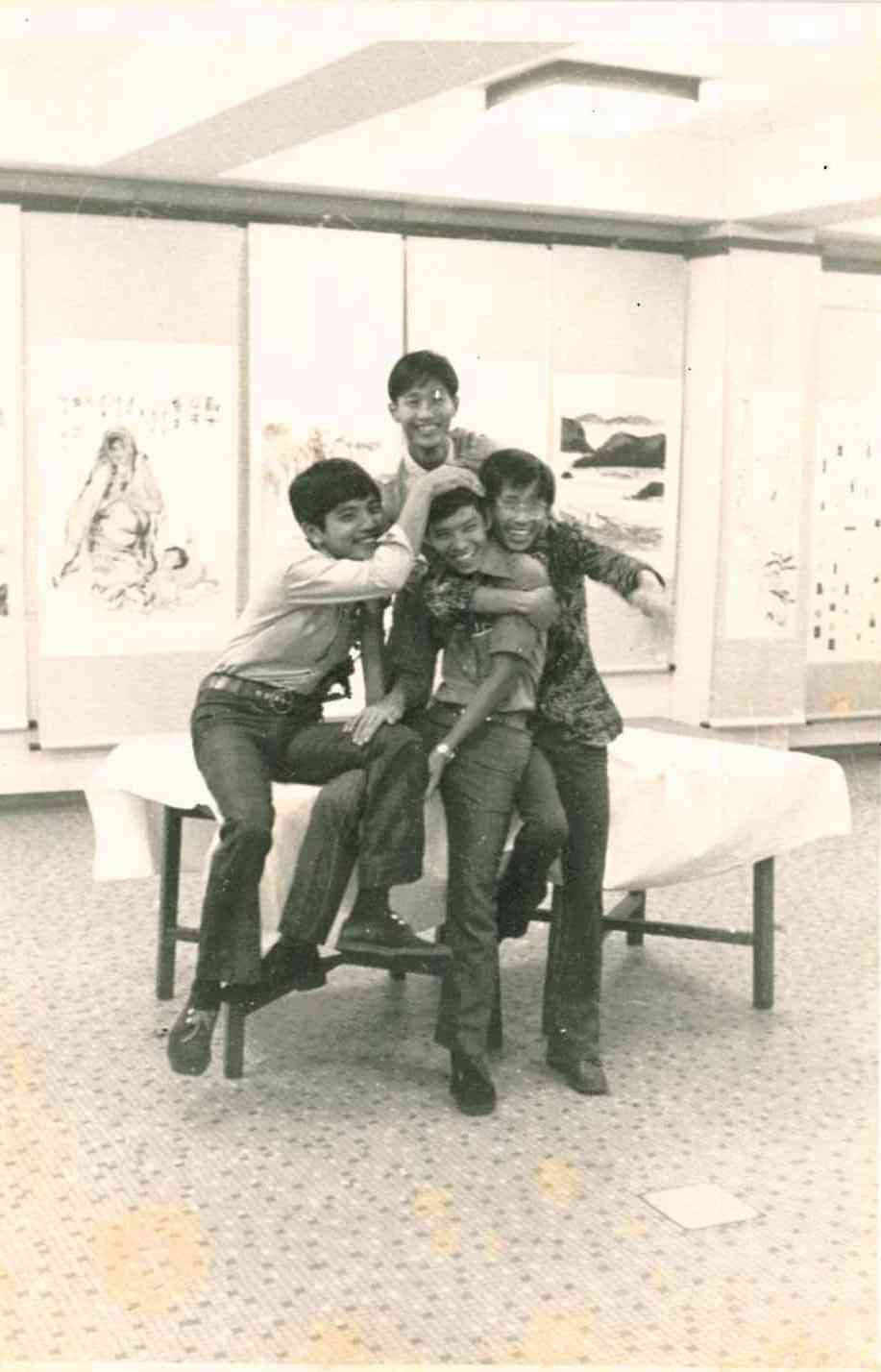

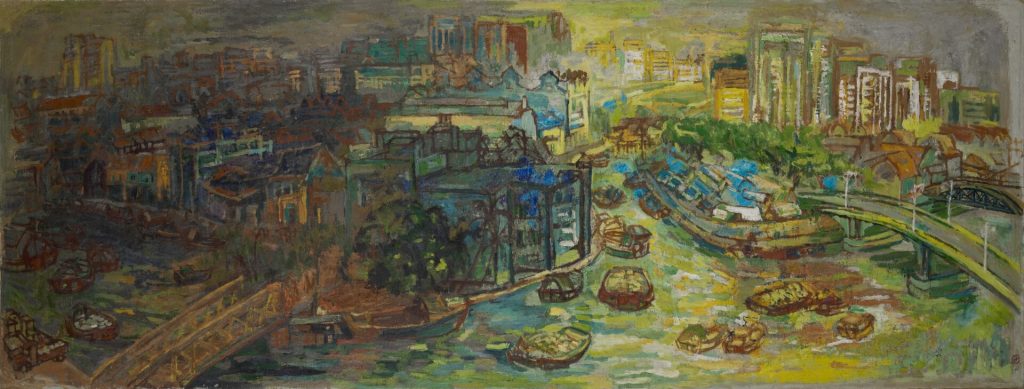

During the 1960s and 1970s, Lim was active in the local art scene. He participated in overseas painting trips organised by the Ten Men Group, spearheaded by his former teacher Yeh Chi Wei.6 Such trips afforded many opportunities for Lim and fellow artists to travel and paint together, where ideas and techniques about art were shared and discussed. During that period, Lim painted mostly in oil. Works on regional and local subjects such as Lake Toba (1970) and Singapore River II (c. 1976) were depicted in a semi-abstract style, characterised by flat planes of strong colours and simplified forms. As an admirer of European artists such as Matisse (1869–1954), Cezanne (1839–1906), Dufy (1877–1953), Constable (1776–1837) and Turner (1775–1851), Lim’s paintings like Sumatra (1970) were rendered with bold expressionistic brushwork and thinly-applied colour layers, leaving sections of the bare canvas unpainted — features often associated with Chinese ink painting.

Works from the 1970s to 1990s

Although painting landscapes primarily in oils then, Lim also started using Chinese ink from the late 1960s onwards to produce lively vignettes of local village life.7 Lim had a close affinity to such subjects as he had spent most of his adult life on a farm, moving out only in his fifties when the family’s farm was acquired for development by the Government in the 1970s. Lim’s switch to the ink medium was likely due to several factors. Given his interest in outdoor landscape painting and strong foundation in Chinese calligraphy, ink was a quick-drying medium which allowed him to complete paintings quickly onsite, sometimes, even producing more than one work per day. Many of Lim’s paintings captured a simpler way of life, closely associated with nature and community ties. Works such as Untitled — Kampong Women (1974) were lyrical depictions of local villagers at work or rest, amid lush tropical vegetation. As Lim recalled, “If you see the coconut trees in the paintings, you know I paint them from within me. I can see the roots, even though they are beneath the ground. I know how they lean, how they allow the wind through their string-like spiky leaves, and most importantly, tree by tree, like old friends, I know how they would enhance a village scene when I add them in a painting.”8

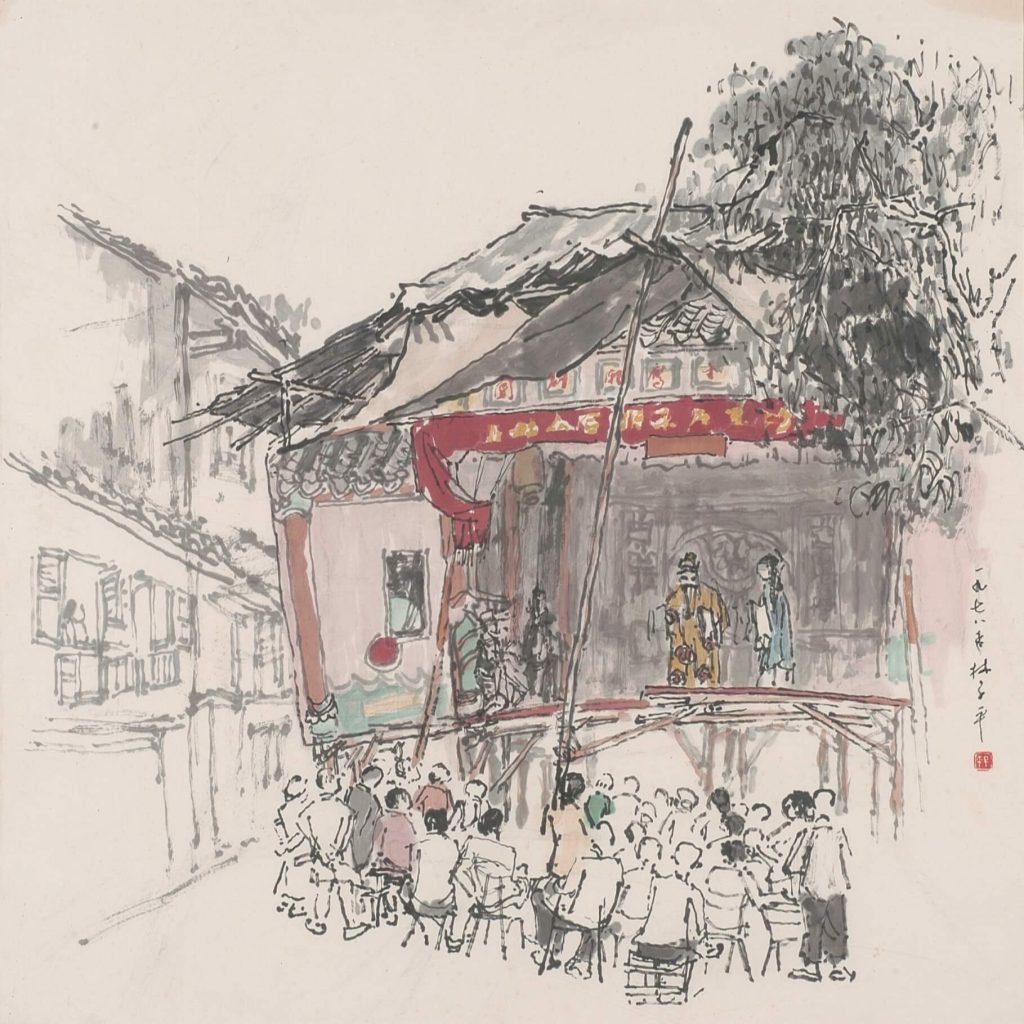

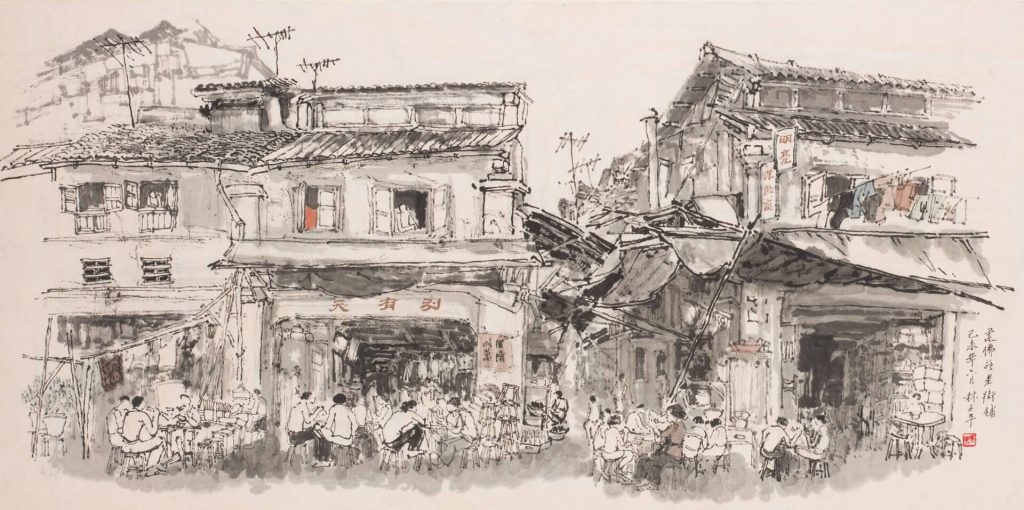

By the 1970s, there was a certain urgency in capturing such scenes as Lim realised that many of such sites were facing inevitable demolishment due to the country’s development needs. In the 1980s, when the authorities turned their attention to the city centre, so did Lim. This coincided with Lim’s retirement in 1981. Buildings which had stood largely unchanged for many decades were being torn down to make way for large modern office and retail complexes. Many small traditional businesses and urban life in the form of bustling street markets and itinerant hawkers were fast disappearing in the wake of greater centralised city planning. The pace of change was so rapid that a scene painted by Lim could disappear the following week. This led Lim to paint outdoors almost every day, in a race against time. Over a decade, he completed a few hundred paintings onsite, documenting traditional shophouses and street scenes of the city’s old quarters, particularly around Chinatown and the Singapore River.9 During that period, Lim used the xieyi (writing the idea) style of ink painting, characterised by quick expressive brushstrokes to capture the essence of a subject. This allowed him to observe and absorb his surroundings in an immediate and direct way. These impressions were then captured as lively vignettes through his deft brushwork and colour washes. Works like Untitled — Chinese Wayang (1978) and Old Shophouse Row at Johor Road (1980–1983) demonstrate Lim’s keen eye for architectural detail, but it is the human element that interests him the most. Be it city streets or rural villages, people are usually present. The latter forms a natural focus, and infuses a sense of liveliness into each painting.

However, Lim was not the first to paint local subjects in ink. In the early 20th century, there were already artists like Chen Chong Swee (1910–1985) who painted tropical subjects using ink. Unlike them, Lim departed from convention in some aspects. Firstly, he seldom painted in the traditional compositional formats of hanging scrolls or hand scrolls. Hence, his works did not adopt the moving aerial perspective usually associated with Chinese landscape painting (shanshui hua). Rather, Lim preferred to work in front of his subject and complete each painting on-site. Hence, his painting paper was usually square in format, which was easier to work on using a portable easel. Secondly, Lim’s keen interest in documenting local architectural heritage meant that he usually adopted a single fixed-point perspective, more commonly found in Western art. Lastly, Lim eschewed the convention of using primarily texture strokes (cunfa) to represent his subject matter. In traditional Chinese landscape painting, artists typically use different texture strokes to build up the painted surface, to suggest mountains, hills, vegetation, lakes and rivers within the composition. However, since Lim needed to work rapidly to capture the ever-changing street life or rural activity in front of him, he used linework to quickly record his visual impressions, supplemented by light ink or colour washes.

Hence, the sense of linearity becomes pronounced in Lim’s paintings, much more so than in the works of other artists like Chen Chong Swee. In the latter’s works, linework is used in almost equal measure with texture strokes and washes. In Lim’s paintings, linework comes to the fore and takes on a life of its own. As an admirer of Chinese painters Huang Binhong (1865–1955) and Li Keran (1907–1989), Lim’s brush lines are never uniform or monotonous, but always lively, and constantly varying in thickness, weight, density and length. In that respect, Lim’s linework was able to capture the dynamic living elements within the landscape in all their infinite variations. Be it a city street or rural village, people and vegetation form a natural focus, and infuse a sense of liveliness into each painting.

A special incident in the 1970s deserves mention. In 1977, on the urging of his close friend and senior artist Cheong Soo Pieng (1917–1983), Lim submitted an ink painting of Bali for the Commonwealth Art Exhibition in London. The local selection committee initially rejected this work as it was deemed neither Western nor Chinese — neither a watercolour nor a Chinese ink painting. Cheong appealed on Lim’s behalf for the work to be reconsidered. Eventually, much to Lim’s surprise, the painting won a special commendation prize in London, the only local work to win a prize in that exhibition. That award bolstered Lim’s confidence to continue with his unconventional approach to ink painting.

Works from the 2000s onwards

By the 2000s, Lim was in his eighties. Due to his advanced age, he eventually stopped his overseas travels and frequent outdoor painting sessions. Spending more time in his studio at home, he could work with much larger pieces of paper, placed on the floor or wall. These afforded him the space to embark on ambitious compositions in ink, whether in painting or calligraphy. Rather than being limited by what he saw, he could now work much more creatively, drawing freely from his sketches and photographs, and synthesising memories with imagination. As Lim recalled, “Now that I am not tied to what I see before me … I have turned inwards to search and explore new images and forms and experiment with them.” 10 He further noted that “I travelled the world, accumulated boundless images in paintings, sketches and notes. Today, I produce art works from this reserve, my mind. It has become my world.” 11

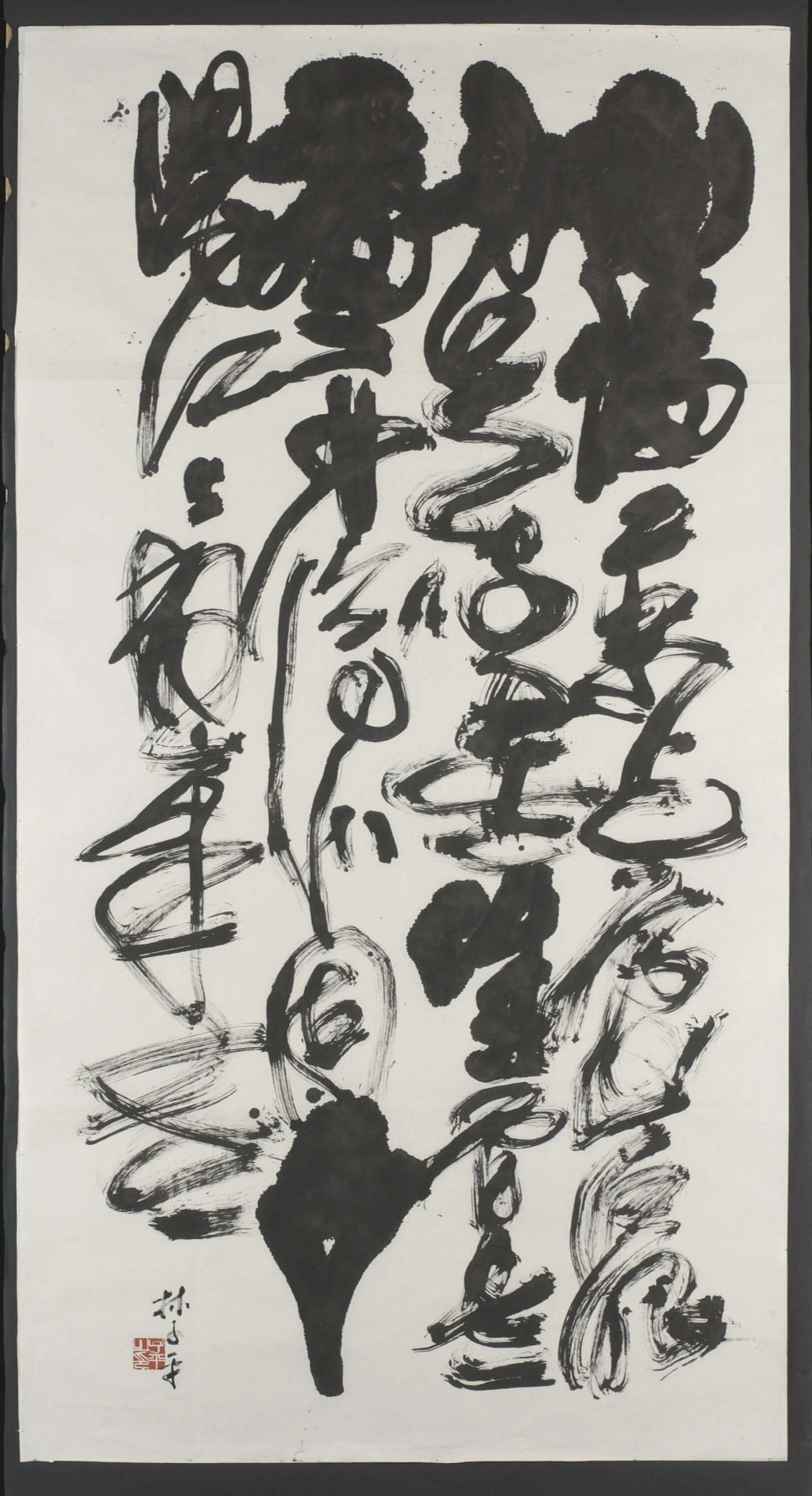

Lim continued with his calligraphic practice, writing daily. By working on larger formats, his writing became much more freely rendered, as seen in works such as Calligraphy VIII (undated). Preferring the more stylised cursive script (caoshu), he wrote with great abandon, often distorting and exaggerating his brushstrokes. His works became less legible as he added bold colours and even wrote overlapping pieces of text. This distinctive style became known as Lim’s “muddled writing” (hutuzi) as his personal expressivity came to the fore, while emphasis on textual content receded into the background. As Lim declared, “I have reached the point in my life where I don’t want to hold on to tradition. I want my work to speak a universal language, the language of abstraction. It is a language where everyone can relate to, no matter where he or she is from.”12 Works like Calligraphy (2000–2002) are strong examples of Lim’s hutuzi.

As a result, Lim’s ink paintings became much more expressive, relying less on representational details and more on the aesthetic potential of calligraphy. For instance, in his depictions of trees, the interlocking branches and roots were rendered in brushwork that recalled Chinese calligraphy, particularly the forceful wild cursive script (kuangcao). In works like Inroads No.1 (2006) and Untitled No.18 — Trees (c. 2008), bold brushwork was applied with great strength and speed, resulting in fierce twists and turns that splatter ink wildly on the paper. Just as the Yuan dynasty artist Zhao Mengfu (1254–1322) had advocated the use of different calligraphic scripts to depict nature, Lim also saw parallels between the forms in nature and Chinese calligraphy.13 He once observed, “I love old trees for their formal beauty in twisted and irregular shapes that can stimulate boundless imagination in the artist … Trees have character, personality and beauty whether crooked or straight. Even if they are thin and craggy, they exude a special charm, especially in the way they bend, curve and meander back and forth.”14 How Lim described the natural beauty of trees applied equally to the formal beauty found in Chinese calligraphy.

From the 1980s onwards, Lim’s works started gaining a higher profile. He had four solo exhibitions in the 1990s, and many more from the 2000s onwards. In 2003, he was awarded the Cultural Medallion — the nation’s highest honour for an artist — by the Singapore government for his outstanding contributions to the local arts scene. This was followed by a landmark exhibition in 2009, where he was invited to showcase his ink works at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing, and his achievements in synthesising Chinese calligraphy and painting were much lauded.

In Singapore, where artists largely kept calligraphy and painting as two distinct areas of practice, Lim was an exception. Among the early painters who were proficient in calligraphy, they either created calligraphy as standalone works, or incorporated calligraphy by way of inscriptions in their paintings. In the latter case, although the calligraphy was considered part of the finished work, it played a secondary role to the painting. In the 1960s, some young artists like Wong Keen and Tan Teo Kwang started using the ink medium and Chinese calligraphy to create modern paintings. However, such experimentations were not sustained and these artists subsequently developed other areas of interest. It was Lim who finally made a breakthrough with his hutuzi in the 2000s. This eventually paved the way for him to use Chinese calligraphy as a foundational core for his powerful ink paintings. This is his enduring legacy in Singapore’s art history.

| 1 | Lim Tze Peng, oral history interview transcript (National Archives of Singapore, 25 Nov 1983), reel 1, 1. |

| 2 | Lim Tze Peng, oral history interview, reel 2, 21. |

| 3 | Lim Tze Peng, oral history interview, reel 2, 36–37. |

| 4 | Lim Tze Peng, oral history interview, reel 3, 44–51. |

| 5 | Lim Tze Peng, oral history interview, reel 6, 102–106. |

| 6 | The Ten Men Group was an informal group of artists who organised overseas painting trips and exhibitions together. They first travelled to the east coast of Malaya in 1961 and then to places such as Java and Bali (1962), Thailand and Cambodia (1964), Sarawak (1965), Sabah, Brunei and Miri (1968), Sumatra (1970), India, Nepal, Burma and Thailand (1971), and India (1972). |

| 7 | The publication My Kampong My Home highlighted that Lim’s earliest Chinese ink painting of local villages dates to 1968. Many of the works completed from the 1960s to the 1980s had never been exhibited before. See Woon Tai Ho, My Kampong My Home, 61. |

| 8 | Woon Tai Ho, Soul of Ink: Lim Tze Peng at 100, 35. |

| 9 | Lim recalled that he worked almost daily, producing one work in the morning and another in the afternoon. He estimated that he completed close to 500 such works in those years. See Lim Tze Peng Interview, video recording, 6–8 August 2007, National Library Board. |

| 10 | Teo Han Wue, Inroads: Lim Tze Peng’s New Works, 28. |

| 11 | Woon, Soul of Ink, 80. |

| 12 | Woon, Soul of Ink, 6. |

| 13 | For instance, Zhao advocated the use of the “flying-white” (feibai) method of the cursive script to draw rocks, and the seal script to outline trees. See Maxwell Hearn, How to Read Chinese Paintings (New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008), 80. |

| 14 | Teo Han Wue, Inroads: Lim Tze Peng’s New Works, 9. |

Lim Tze Peng, oral history interview by Pitt Kuan Wah and Lye Soo Choon, 25 Nov 1983, transcript and audio, National Archives of Singapore (accession no. 000370), Reel/Disc 1–12. | |

Teo, Han Wue. Inroads: Lim Tze Peng’s New Works. Singapore: Art Retreat Ltd, 2008. | |

Woon, Tai Ho. My Kampong My Home. Singapore: Friends of Lim Tze Peng, 2010. | |

Woon, Tai Ho. Soul of Ink: Lim Tze Peng at 100. Singapore: World Scientific Publishing Co. Pte. Ltd., 2021. |